Crawl (2019)

It is no secret that the film industry relies on a handful of common tropes as the mainstay of their cinematic output. It uses timeless themes, storylines and archetypes that have featured in folk tales, plays and literature throughout history. Hence their familiarity with audiences around the world. Where the skill in filmmaking lies is to take a common, well known idea and interpret it in a new and innovative fashion. Akira Kurosawa took Shakespeare’s MacBeth and retold the tale through the prism of Japanese feudalistic culture. The result, Throne of Blood, is considered a masterpiece. Similarly, The Lion King retells the same story through the medium of animation and anthropomorphic wildlife. All of which proves that the key to successfully retelling a familiar tale is to be creative with regard to setting, presentation and perspective.

It is no secret that the film industry relies on a handful of common tropes as the mainstay of their cinematic output. It uses timeless themes, storylines and archetypes that have featured in folk tales, plays and literature throughout history. Hence their familiarity with audiences around the world. Where the skill in filmmaking lies is to take a common, well known idea and interpret it in a new and innovative fashion. Akira Kurosawa took Shakespeare’s MacBeth and retold the tale through the prism of Japanese feudalistic culture. The result, Throne of Blood, is considered a masterpiece. Similarly, The Lion King retells the same story through the medium of animation and anthropomorphic wildlife. All of which proves that the key to successfully retelling a familiar tale is to be creative with regard to setting, presentation and perspective.

Which neatly brings me to Crawl. A creature feature where the central “McGuffin” is a group of people trapped by wayward wildlife. Hollywood has explored this plot device many times before. Consider The Naked Jungle (1954) in which Charlton Heston faces a swarm of South American ants. Then there is Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). More recently Bait (2012) features a group of people trapped in a flooded supermarket along with a Great White Shark after a tsunami. Crawl (2019) has a father and daughter trapped in a house during a hurricane. Due to the Florida setting the dangerous beasties are Alligators on this occasion. What makes the film a cut above the average genre outing is a solid script with plausible characters and a decent cast that give life to the proceedings. Director Alexandre Aja builds a genuine sense of tension and punctuates the 87 minute running time with some robust set pieces.

Filmed in Belgrade, the production seamlessly recreates Florida. The digital effects convincingly depict a hurricane and the Alligators are a mixture of animatronics and CGI. But the film’s greatest assets are the main performances by Kaya Scodelario as Haley Keller and Barry Pepper as Dave Keller. Daughter Haley is an aspiring swimmer and her estranged father Dave is her former coach. The screenplay by Michael Rasmussen and Shawn Rasmussen keeps the scope of the narrative simple and immediate, resulting in a plausible family dynamic. The wider cast is minimal and although some characters are merely “red shirts” intended to expedite the threat of the Alligators with their timely deaths, the screenplay doesn’t treat them in a totally arbitrary fashion. The scenes of violence, are well realised, suspenseful and surprisingly unpleasant.

Crawl is content to stick within the parameters it has set itself and concentrates on telling its story to the best of its ability. There is an assumption from some critics that genre movies are by their nature, no more than the sum of their parts. Those with a more enlightened perspective believe that all types of film can craft well told stories and explore deep themes. Crawl is a prime example of an old story told from a fresh and different perspective. Yes, it does include horror elements but that is not all that it has to offer. At its heart this is a film about the perennial theme of fathers and daughters, which Crawl explores this well. It also has a point to make about climate change. However, if you’re just looking for a quality creature feature, complete with jump scares and grisly shocks, then the film also delivers this in spades.

Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio (2022)

Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio is a bold and inventive take on Carlo Collodi's classic story of the puppet that aspires to be a “real boy”. As you would expect from the director, it is a far cry from Disney’s 1940 version, taking a more bleak and sinister tone. Despite songs and exuberant set pieces, Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio is an exploration of grief, death and even fascism. The screenplay by Guillermo del Toro and Patrick McHale also tackles the complexities of the relationship between parent and child. It is a remarkable example of stop motion animation and is visually very striking. However, it is a somewhat niche market adaptation and is not exactly easily accessible to children or the furiously hard of thinking. It comes as no surprise that this cinematic venture was green lit by Netflix, which appears to be the new home of the experimental, rather than a mainstream studio.

Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio is a bold and inventive take on Carlo Collodi's classic story of the puppet that aspires to be a “real boy”. As you would expect from the director, it is a far cry from Disney’s 1940 version, taking a more bleak and sinister tone. Despite songs and exuberant set pieces, Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio is an exploration of grief, death and even fascism. The screenplay by Guillermo del Toro and Patrick McHale also tackles the complexities of the relationship between parent and child. It is a remarkable example of stop motion animation and is visually very striking. However, it is a somewhat niche market adaptation and is not exactly easily accessible to children or the furiously hard of thinking. It comes as no surprise that this cinematic venture was green lit by Netflix, which appears to be the new home of the experimental, rather than a mainstream studio.

In Italy during World War I, a carpenter Geppetto (David Bradley) in a small village loses his son, Carlo (Gregory Mann), during an aerial bombardment by Austro-Hungarian forces. Geppetto plants a pine cone near his grave and spends the next twenty years grieving. A cricket named Sebastian J. Cricket (Ewan McGregor) takes up residence in the pine tree that subsequently grows. One day, angered by his prayers to restore his son being ignored, Geppetto cuts the tree down in a fit of drunken rage and makes a new son out of the wood. He leaves the puppet unfinished when he passes out, but the blue Wood Sprite takes pity upon him and brings the puppet to life, christening him Pinocchio (Gregory Mann again). The Sprite encounters Sebastian who lives in Pinocchio’s chest and promises to grant him a wish if he acts as Pinocchio's guide and conscience.

Although the essential “beats” of both the original story and Disney’s adaptation are present in Del Toro’s film, there are elements of Frankenstein as well as nods to Spielberg’s AI: Artificial Intelligence (2001) and Clive Barker’s Nightbreed (1990). Pinnochio is the archetypal “monster” who ironically is more human than his antagonists. Del Toro eschews the rather clumsy metaphor of a physical transformation into a real boy and instead explores the theme as a spiritual and philosophical journey. He even manages to touch upon the allure of fascism to the young, when Italian authorities take an interest in Pinocchio due to his undying nature. As ever magic is a force of nature, neither entirely benign or evil and this is reflected in the two Sprites that feature in the story. Both boast a Chimera like appearance which Del Toro has explored in previous films and have flawed motives.

The production design and creative supervision are outstanding with the film drawing heavily upon such diverse visual influences as Norman Rockwell and Hieronymus Bosch. Composer Alexandre Desplat provides a melancholic and tragic soundtrack and Del Toro co-wrote the lyrics to the songs that punctuate the two hour running time. Again these are not the celebratory or validatory numbers one associates with mainstream animated films. These are far more forlorn and heartbreaking. Yet they work within the context of the film. Guillermo del Toro's unique approach to filmmaking manages to pull all these eclectic elements together. His recurring themes of life, death and difference underpin this imaginative and bold retelling of Pinnochio. Fans of his work will embrace it, as will lovers of quality cinema and animation. Casual viewers may well struggle with such a radical variation on a theme.

Speak No Evil (2022)

The plot of Speak No Evil is an exploration of what can happen when someone driven by a cultural urge to be polite and avoid any form of confrontation, encounters a psychopath who exploits their very nature. Speak No Evil is a very European psychological horror and I stress that point because this film will not necessarily play well to audiences who are not so familiar with such institutionalised deference or passivity. Danish writer and director Christian Tafdrup skilfully and slowly builds the tension, but the plot contrivances of the final act do somewhat mitigate its credibility. Hence realism gives way purely to threat and suspense. If you’re the sort of viewer who can countenance that different cultures, age groups and political leanings can dramatically impact upon one’s behaviour, then you may well get through Speak No Evil. If you struggle to come to terms with the poor decisions made in an episode of Scooby Doo then Speak No Evil will leave you screaming at your TV.

The plot of Speak No Evil is an exploration of what can happen when someone driven by a cultural urge to be polite and avoid any form of confrontation, encounters a psychopath who exploits their very nature. Speak No Evil is a very European psychological horror and I stress that point because this film will not necessarily play well to audiences who are not so familiar with such institutionalised deference or passivity. Danish writer and director Christian Tafdrup skilfully and slowly builds the tension, but the plot contrivances of the final act do somewhat mitigate its credibility. Hence realism gives way purely to threat and suspense. If you’re the sort of viewer who can countenance that different cultures, age groups and political leanings can dramatically impact upon one’s behaviour, then you may well get through Speak No Evil. If you struggle to come to terms with the poor decisions made in an episode of Scooby Doo then Speak No Evil will leave you screaming at your TV.

Speak No Evil superficially is the story of a Danish family who befriends a Dutch family while on holiday. Formal and polite, Bjørn (Morten Burian) and Louise (Sidsel Siem Koch) are enamoured and impressed by the brash Patrick (Fedja van Huêt) and the warmth of Karin (Karina Smulders). Their much beloved daughter Agnes (Liva Forsberg) finds a companion in Patrick and Karin's shy and retiring son Abel (Marius Damslev). After the holiday, when a postcard arrives inviting them to spend a weekend with their new friends in their remote, rural cabin in the Dutch countryside, it seems like a perfect opportunity to further enjoy the new family friendship. “What's the worst that could happen?” Bjørn jokes, ironically telegraphing that the worst is not only coming but that it is going to be a very grim journey.

The cast of Speak No Evil is very good as they experience social faux pas then physical coercion. Morten Burian (Bjørn) is infuriatingly passive, self loathing and conflicted but his performance is worryingly credible. Sidsel Siem Koch (Louise) seems genuinely intimidated by Fedja van Huêt (Patrick) who exudes volatility, where Karina Smulders (Karin) is deliberately ill defined. Is she also being coerced or a more subtle manipulator? However, despite solid performances, Speak No Evil struggles to maintain all the themes and motifs it touches upon during its first act. The big reveal it’s been heading towards is a little too contrived and once it has been established, the protagonist's behaviour becomes hard to identify with. When the violence comes it is quite stark and jarring. The ending doesn’t answer the question of motive, relying on the old trop of “evil people are evil”.

Speak No Evil has some good ideas at its core. One could argue that it explores many talking points about contemporary culture and gender roles. Are modern European men too worried about risk and conflict? Has the modern habit of self examination gone too far and left those who do so powerless to make decisions? Is the need to please a social blessing or a curse? However, a better film would bring us to the conclusion via a less obvious route. It becomes very clear that Speak No Evil is going from A to B to C come hell or highwater and it shows in the final act. Furthermore, I have no problems with horror films with a message. Dawn of the Dead, for example, is as pertinent today as it was back in 1978. But I’m seldom impressed when a message driven story co-opts the horror genre out of convenience. It strikes me as very insincere and confected. And that is how I felt after watching Speak No Evil. That and the fact that the film seems too pleased with itself, when it really has no right to be.

Treasure of the Four Crowns (1983)

“In the universe there are things man cannot hope to understand. Powers he cannot hope to possess. Forces he cannot hope to control. The Four Crowns are such things. Yet the search has begun. A soldier of fortune takes the first step. He seeks a key that will unlock the power of the Four Crowns and unleash a world where good and evil collide”. So reads the Star Wars-esque opening crawl for the 1983 3D action movie, Treasure of the Four Crowns. It’s worth noting that when it appears on screen, this text is written in capitals and devoid of any punctuation. The movie is also a Cannon Films production. These facts may give viewers an inkling of what is to come over the next 100 minutes. It is certainly best to abandon expectations of linear, narrative filmmaking. Treasure of the Four Crowns is unique, batshit crazy and yet curiously entertaining.

“In the universe there are things man cannot hope to understand. Powers he cannot hope to possess. Forces he cannot hope to control. The Four Crowns are such things. Yet the search has begun. A soldier of fortune takes the first step. He seeks a key that will unlock the power of the Four Crowns and unleash a world where good and evil collide”. So reads the Star Wars-esque opening crawl for the 1983 3D action movie, Treasure of the Four Crowns. It’s worth noting that when it appears on screen, this text is written in capitals and devoid of any punctuation. The movie is also a Cannon Films production. These facts may give viewers an inkling of what is to come over the next 100 minutes. It is certainly best to abandon expectations of linear, narrative filmmaking. Treasure of the Four Crowns is unique, batshit crazy and yet curiously entertaining.

Soldier of Fortune, J.T. Striker (Tony Anthony), is hired by Professor Montgomery to assemble a group of professional thieves to retrieve gemstones which are hidden inside two ancient and Mystical Crowns. These crowns are a part of four. One is already in the Professor’s possession. The other was destroyed by the Moors when they attempted to access its “power”. Striker recruits professional thief Rick (Jerry Lazarus), as well as acrobats and circus performers Liz (Ana Obregon) and her Father Socartes (Francisco Rabal). They are joined by Striker’s friend and Professor Montgomeries agent Edmond (Gene Quintano). The team must infiltrate a heavily fortified compound in a small mountain village that is home to a religious cult. Its leader Brother Jonas (Emiliano Redondo) has the crowns protected by an advanced and deadly security system.

The aforementioned plot sounds fairly straightforward on paper, but what transpires is nothing of the sort. The film begins with Striker infiltrating an old Spanish castle to the strains of a wonderfully portentous soundtrack written by the great Ennio Morricone. There is no dialogue for the next twenty minutes as Striker is subject to a succession of attacks from vultures, wild dogs, rubber pterodactyls, floatings swords and crossbows, balls of fire, all while being mocked by ghostly jeers and cries emanating from the skeletal corpses of long dead knights. And when he finally escapes with a gold key, the entire castle explodes for some particular reason. It makes very little sense and nothing is explained as to why the castle is booby trapped, haunted or contains prehistoric flying reptiles. There are however more 3D effects in this opening sequence than there are in other entire 3D feature films.

The film then continues in the same vein. Scenes of exposition appear from time to time, linking a series of increasingly crazy 3D set pieces. The key appears to have supernatural powers causing at one point Rick’s cabin to erupt into mayhem. This includes teapots and dried food storage jars exploding in slow motion and showering the camera lens in beans and lentils. The dialogue desperately tries to be hard boiled but often comes off as rather sarcastic as if the very cast are passive aggressively trolling the very film they’re appearing in. When Brother Jonas finally appears he is presented as a Charles Mansonesque faith healer with a cult of armed followers, wearing a mixture of World War II partisan clothing and pig masks. In a scene where he allegedly heals a crippled follower to impress a group of new converts, the rather disturbing atmosphere is quickly mitigated when he clumsily winks at the afflicted to telegraph the fact that the entire ceremony is just an act.

The final act of Treasure of the Four Crowns sees the team assemble a series of cables, pulleys and ad hoc trapeze to bypass the security features in the hall where the crowns are kept. The ominous statue that houses them is inevitably booby trapped and triggers an alarm. Brother Jonas and his cohorts arrive, just as Striker grasps the magical jewels contained within the crowns. The film then strays into another genre as he is possessed, his head spins round and half of his face becomes monstrous. He then proceeds to unleash fire and pyrotechnics as Morricone score desperately tries to apply some musical dignity to the spiralling insanity. Viewers are then treated to several full burn stunts and the laser alarm system turns fatal and starts cutting Brother Jonas into pieces. It is a massive tonal shift that will either delight viewers or invoke their scorn at its preposterous nature.

Treasure of the Four Crowns is clearly designed to ride on the coattails of Raiders of the Lost Ark. 3D films were also a cinematic trend at the time and Cannon Films has already made the successful and equally silly film Comin’ at Ya! two years earlier. The production team behind Treasure of the Four Crowns were clearly only interested in a vehicle that could facilitate a plethora of action set pieces that showcase the 3D format. Like many Italian co-productions from this decade, the prevailing attitude is “never mind logic and continuity, throw everything in, bar the kitchen sink”. So the film goes large with the practical effects and culminates in a singularly bizarre cinematic postscript featuring a pulsing sac which spawns some sort of monster which leaps toward the camera. It is all quite mad and yet strangely compelling. Morricone’s score does much of the heavy lifting. Treasure of the Four Crowns is the very definition of a cult film. If you choose to watch it you’ll either love it or loathe it.

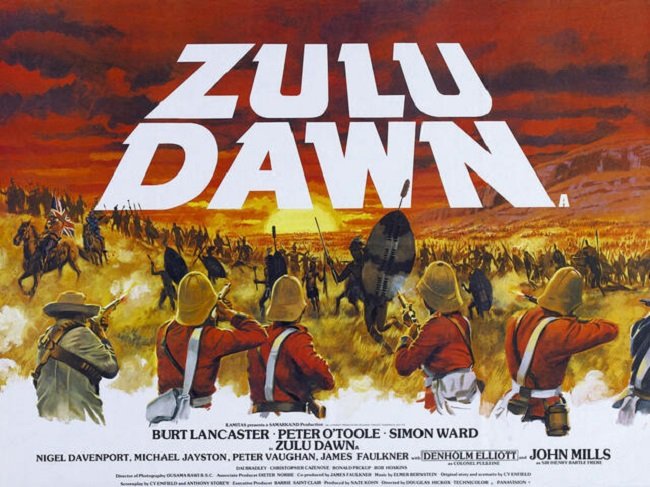

Zulu Dawn (1979)

Zulu (1964) recounts the Battle of Rorke’s Drift between the British Army and the Zulus in January 1879. Directed, produced and co-written by Cy Endfield the film presents an action filled account of how 150 British soldiers, 30 of whom were sick and wounded, successfully held off a force of 4,000 Zulu warriors. Although well made and rousing, it is very much a film from the British perspective. Despite depicting the Zulu nation fairly, the film makes no attempt to put the clash between two empires in any sort of wider context. Zulu Dawn is a direct prequel which shows the events that directly lead up to the Battle of Rorke’s Drift. Much more time is dedicated to exploring the Zulu’s position as their leader King Cetshwayo attempts to avoid the political fait accompli he has been presented with. Furthermore, Zulu Dawn does not in any way try to avoid the failure of the British chain of command that resulted in the defeat of 1,300 British soldiers at the Battle of Isandlwana.

Zulu (1964) recounts the Battle of Rorke’s Drift between the British Army and the Zulus in January 1879. Directed, produced and co-written by Cy Endfield the film presents an action filled account of how 150 British soldiers, 30 of whom were sick and wounded, successfully held off a force of 4,000 Zulu warriors. Although well made and rousing, it is very much a film from the British perspective. Despite depicting the Zulu nation fairly, the film makes no attempt to put the clash between two empires in any sort of wider context. Zulu Dawn is a direct prequel which shows the events that directly lead up to the Battle of Rorke’s Drift. Much more time is dedicated to exploring the Zulu’s position as their leader King Cetshwayo attempts to avoid the political fait accompli he has been presented with. Furthermore, Zulu Dawn does not in any way try to avoid the failure of the British chain of command that resulted in the defeat of 1,300 British soldiers at the Battle of Isandlwana.

Fearing that the Zulus are becoming too powerful in the region, Lord Chelmsford (Peter O'Toole) plots with diplomat Sir Henry Bartle Frere (John Mills) to annex the neighbouring Zulu Empire, despite there being an existing treaty in place. Subsequent demands to demilitarise are rejected by King Cetshwayo (Simon Sabela) giving Lord Chelmsford casus belli to invade. Prior to embarking into Zulu territory the British forces are reinforced with native troops and the Natal Mounted Police. However, the Zulus refuse to directly engage the British forces and pursue guerilla attacks. The British expeditionary force subsequently makes camp at Mount Isandlwana but rejects the advice from the Boer contingents to fortify the camp around the ammunition wagons. Lord Chelmsford divides his forces and heads a column to pursue bogus sightings of Zulu forces. Meanwhile the Zulu army masses near Isandlwana, preparing to engage the British camp.

Zulu Dawn takes time in setting the scene and explaining the historical situation. The first act cuts between a garden party being held by Sir Henry Bartle Frere, High Commissioner for Southern Africa and celebrations at Zulu capital, Ulundi. Both events provide a backdrop to ongoing political machinations. The screenplay by Cy Endfield cleverly uses the casual conversations between the officers wives and regional Missionaries to summarise the hubris and condescension of the British in Natal at the time. The disposition of the troops is also explored through the relationships between Colour Sergeant Williams (Bob Hoskins) and raw recruit Private Williams (Dai Bradley). Quartermaster Sergeant Bloomfield (Peter Vaughan) is shown to be a “jobsworth” and instrumental in contributing to the deteriorating situation at the film’s climax. Col. Durnford (Burt Lancaster) is shown to be savvy and well versed in fighting the Zulus. Hence his advice is scorned by his British superiors due to his Irish heritage.

The second act of Zulu Dawn follows the British as they make a series of ill conceived decisions after crossing into Zulu territory. Cinematographer Ousama Rawi makes effective use of the rugged South African terrain. The climax of the film follows in detail the attack upon the British lines by the Zulu and how they overwhelmed them. The subsequent retreat became a rout and one of the most serious defeats for British forces in their military history. Although not excessively explicit in its depiction of violence, director Douglas Hickox does well in depicting the growing sense of fear and disbelief among the British troops as they realise that the tide of the battle is rapidly turning against them. The failure to get ammunition from the wagons to the troops is a major factor. I suspect that the film’s depiction of a major defeat, rather than the usual narrative of the plucky underdog who wins despite the odds may discourage some viewers. Zulu Dawn is more likely to engage those seeking historical authenticity rather than pure action.

Tales of Terror (1962)

Directed by Roger Corman, Tales of Terror is an anthology horror film based upon three short stories by Edgar Allan Poe. “Morella”, “The Black Cat” and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar”. Adapted by Richard Matheson, the screenplay offers a ghoulish tale of revenge, a humorous story of a drunk who murders his wife and her lover and a sinister story of a mesmerist who hypnotises a terminally ill man at the point of death. Deftly produced and looking far more sumptuous than you’d expect from such a modest budget film, Tales of Terror benefits from a strong cast of old school, Hollywood character actors. The anthology format affords each story a fairly prompt and ghoulish climax and as ever with the films of Roger Corman from this period, visual creativity and innovation elevate the proceedings above the standard exploitation fare of the time.

Directed by Roger Corman, Tales of Terror is an anthology horror film based upon three short stories by Edgar Allan Poe. “Morella”, “The Black Cat” and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar”. Adapted by Richard Matheson, the screenplay offers a ghoulish tale of revenge, a humorous story of a drunk who murders his wife and her lover and a sinister story of a mesmerist who hypnotises a terminally ill man at the point of death. Deftly produced and looking far more sumptuous than you’d expect from such a modest budget film, Tales of Terror benefits from a strong cast of old school, Hollywood character actors. The anthology format affords each story a fairly prompt and ghoulish climax and as ever with the films of Roger Corman from this period, visual creativity and innovation elevate the proceedings above the standard exploitation fare of the time.

Tales of Terror is the fourth entry into the Roger Corman’s series of adaptations of the work of Edgar Allan Poe and the first to use the portmanteau format. Vincent Price makes a return after being absent in the previous entry Premature Burial which starred Ray Milland. Price demonstrates his acting prowess not only in three lead roles but by also providing the linking narration that frame all the stories. The short nature of each story doesn’t afford an opportunity for any in depth character development, hence the presence of a cast of robust and charismatic actors is invaluable in bolstering the narrative. The financial success of the previous instalments of the series meant that there was a greater budget available for the cast. Hence Price is joined by two stalwarts from the golden age of Hollywood; Peter Lorre and Basil Rathbone.

As ever with Corman productions, the production design by Daniel Haller is handsome and the sets are cleverly contrived to look more opulent than they actually are. Many have been recycled from previous production. Cinematographer Floyd Crosby, a long time collaborator of Roger Corman productions, lights the proceedings in an atmospheric way. This is especially noticeable in the last story, in which the mutlicoloured light used by mesmerist Mr. Carmichael (Basil Rathbone), bathes the actors in red, blue and yellow light in turn. There are also several sequences that use optical effects to distort the film image and give the stories a suitably supernatural ambiance. They also mask the basic nature of some of the make up effects. Legendary special effects artist Albert Whitlock created two notable matte paintings for the film. The Locke residence next to the sea and the Valdemar mansion nestled among the trees.

Tales of Terror presents an interesting change of approach from the earlier Roger Corman adaptations of the work of Edgar Allan Poe. The anthology format has both strengths and weaknesses. It provides a convenient means to swiftly build up to a climatic shock and offers three stories instead of one. Yet the strong cast have to rely on their established cinematic personalities to carry each story, as the script doesn’t offer much beyond what you see. Perhaps the most noticeable deviation from prior Poe adaptations is the humorous tone of the second story, The Black Cat. Peter Lorre is an amusing drunk and doesn’t really come across as a potential threat and murderer. However, despite this tonal shift, Tales of Terror remains a well crafted and enjoyable example of US Gothic horror form the sixties. Although similar in many ways to the UK’s Hammer productions, Corman’s work has a very different look and feel to it.

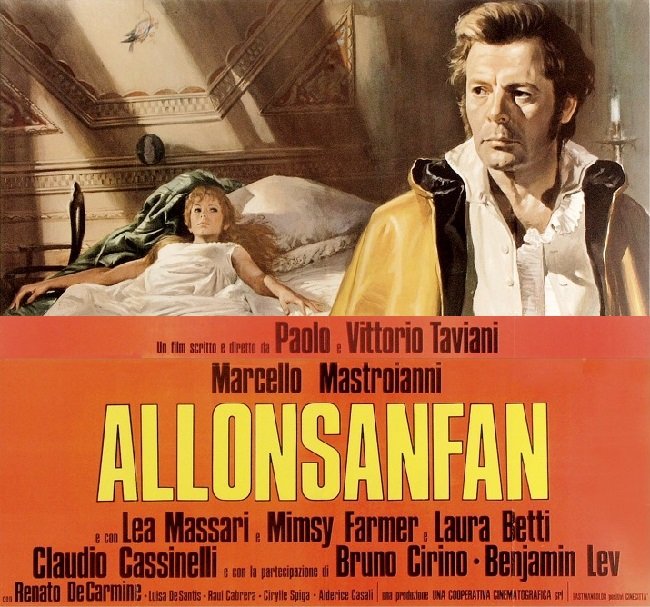

Classic Movie Themes: Allonsanfàn

Allonsanfàn (1974) is an Italian historical drama film written and directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani. The title of the film derives from the first words of the French Revolutionary anthem La Marseillaise (Allons enfants, IE “Arise, children”). It is also the name of a character in the story. Set against the backdrop of the Italian Unification in early 19th-century Italy, Marcello Mastroianni stars as an ageing revolutionary, Fulvio Imbriani, who becomes disillusioned after the Restoration and endeavours to betray his companions, who are organising an insurrection in Southern Italy. Allonsanfàn is a complex film that is not immediately accessible to those unfamiliar with the intricacies of Italian political history nor the arthouse style of the Taviani brothers. However, it is visually arresting and features a rousing score by Ennio Morricone.

Allonsanfàn (1974) is an Italian historical drama film written and directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani. The title of the film derives from the first words of the French Revolutionary anthem La Marseillaise (Allons enfants, IE “Arise, children”). It is also the name of a character in the story. Set against the backdrop of the Italian Unification in early 19th-century Italy, Marcello Mastroianni stars as an ageing revolutionary, Fulvio Imbriani, who becomes disillusioned after the Restoration and endeavours to betray his companions, who are organising an insurrection in Southern Italy. Allonsanfàn is a complex film that is not immediately accessible to those unfamiliar with the intricacies of Italian political history nor the arthouse style of the Taviani brothers. However, it is visually arresting and features a rousing score by Ennio Morricone.

The Tavianis brothers’ previous composer Giovanni Fusco introduced Morricone to the directors, who initially didn't want to use any original music for the film. As Morricone was not disposed towards arranging anyone else's work he insisted upon writing his own material or he would leave the production. Upon hearing the motif he created for the climatic “dance” scene, the Tavianis brothers immediately set aside their previous objections and gave Morricone free reign. Hence, Morricone’s deliciously inventive score is part of the fabric of the film, providing a pulse to the story. This is most noticeable in the scene in which Fulvio’s sister Esther (Laura Betti) turns a half-remembered revolutionary song into a full-blown song-and-dance number and when Fulvio himself borrows a violin in a restaurant to impress his son. Allonsanfàn may not be to everyone’s taste but Morricone’s score is very accessible.

Perhaps the most standout track from the film’s score is “Rabbia e tarantella” (Revolution and Tarantella). A Tarantella is a form of Italian folk dance characterised by a fast upbeat tempo. Morricone has crafted a remarkably rhythmic piece featuring aggressive piano and low-end brass against a backdrop of a stabbing string melody. All of which is driven and underpinned by the timpani drum which robustly punctuates the track. It is certainly not your typical tarantellas of Italian folk but it is a catchy piece that highlights the innate understanding of music that Ennio Morricone possessed and how he could bring this talent to bear on any cinematic scene. “Rabbia e tarantella” was subsequently used during the closing credits of Quentin Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds (2009). Due to its inherent quality it survives being transplanted into a film with a completely different context.

Scream and Scream Again (1970)

I first saw Scream and Scream Again as a teenager while watching late night television. I was expecting the usual sort of lurid, seventies, exploitation horror and much to my surprise was met with something quite different. The film left a marked impression upon me and so I decided to re-watch it recently. This second viewing only further compounded my sense of surprise. Scream and Scream Again was clearly marketed as a horror film upon release but it strays more into the science fiction genre. I was reminded of Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers and there is a further hint of conspiracy thrillers such as The Parallax View. Although a low budget film, quickly made to meet production schedule and fill a gap in the market, Scream and Scream Again has an intriguing premise and is presented in an engaging format, with three seemingly separate stories coming together to form a rather sinister conclusion. There are more ideas here than you’ll find in many big budget contemporary movies.

I first saw Scream and Scream Again as a teenager while watching late night television. I was expecting the usual sort of lurid, seventies, exploitation horror and much to my surprise was met with something quite different. The film left a marked impression upon me and so I decided to re-watch it recently. This second viewing only further compounded my sense of surprise. Scream and Scream Again was clearly marketed as a horror film upon release but it strays more into the science fiction genre. I was reminded of Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers and there is a further hint of conspiracy thrillers such as The Parallax View. Although a low budget film, quickly made to meet production schedule and fill a gap in the market, Scream and Scream Again has an intriguing premise and is presented in an engaging format, with three seemingly separate stories coming together to form a rather sinister conclusion. There are more ideas here than you’ll find in many big budget contemporary movies.

A jogger running through suburban London collapses in the street. He wakes up in a hospital bed, tended by a mute nurse. He lifts the bed sheets to discover his right leg has been amputated. He starts to scream. Elsewhere, in an unidentified Eastern European totalitarian state, intelligence operative Konratz (Marshall Jones) returns home for a debriefing with his superior, Captain Schweitz (Peter Sallis). During the meeting Konratz reveals some information he isn’t supposed to know, arousing Schweitz’s suspicion. Konratz calmly kills him by placing his hand on his shoulder, paralysing him. In London Detective Superintendent Bellaver (Alfred Marks) investigates the rape and murder of a young woman, Eileen Stevens. Supt. Bellaver and forensic pathologist Dr. David Sorel (Christopher Matthews) interview her employer Dr. Browning (Vincent Price) who is unable to provide any information. Meanwhile another young woman, Sylvia (Judy Huxtable), is picked up by a tall man named Keith (Michael Gothard) at a nightclub. She later found dead and completely drained of blood

Scream and Scream Again has a strong cast featuring horror stalwarts such as Vincent Price, Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing. However due to the three distinct story lines they do not often cross paths or share much screen time together. Performances are solid with British character actors such as Peter Sallis and Julian Holloway filling minor roles. The screenplay by Christopher Wicking is fast paced and handles the complexity of the different plot threads well. Alfred Marks has some suitably droll and cynical dialogue that is becoming of a senior and cynical career police officer. Again I must mention that the proceedings feel far more like a thriller. There’s a particularly well staged car chase in a rural setting, culminating at a chalk quarry, which has a real sense of speed and inertia. The night club scene briefly features the Welsh psychedelic rock group Amen Corner who also provide a song which plays over the end credits.

For those who are expecting a bonafide horror film, then there’s little on screen violence. The storyline featuring the jogger who has his limbs amputated one by one is disconcerting but far from graphic as you only ever see him recovering in bed. The nightclub serial killer is similarly far from graphic with the emphasis on him chasing his prey. Yet despite the absence of overt violence, there is a very unsettling undertone to Scream and Scream Again and it builds to a suitably grim climax. The film’s modest budget does let it down in some areas. The make up and practical special effects are somewhat cheap, especially the acid bath which appears mainly to be dishwashing detergent. Yet despite these minor shortcomings, the film is a prime example of low budget innovation and how good ideas can carry a production. Scream and Scream Again stands out because it is not afraid to do something different. It is not only a genre anomaly but also a rather interesting and enjoyable film.

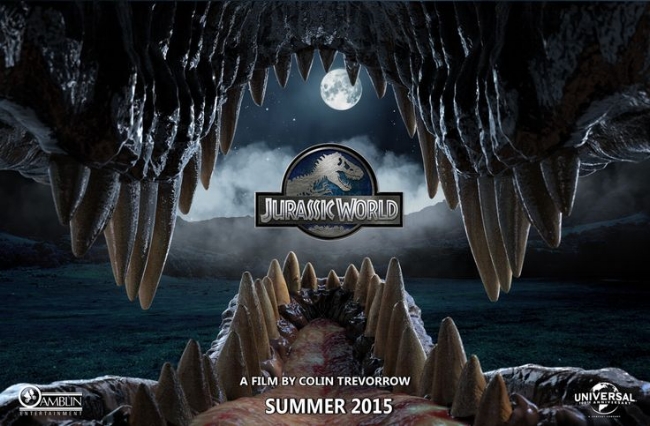

Jurassic World Dominion (2022)

Jurassic World Dominion is a textbook example of a franchise that has run out of steam. Despite the enormous budget, the top notch production values and the presence of three members of the original cast, this is a long, tedious and curiously uneventful film. It has nothing new to say about environmental matters or unfettered science; themes that were front and centre in previous instalments. Nor does it do anything interesting with the main plot device of dinosaurs trying to integrate into our current ecosystems. But perhaps its biggest failing is the conspicuous lack of tension. The denizens of Jurassic World are simply not a threat and fail to have any emotional impact. The film doesn’t even placate viewers with superfluous cast members being eaten. The onscreen deaths by dinosaurs are rather tame.

Jurassic World Dominion is a textbook example of a franchise that has run out of steam. Despite the enormous budget, the top notch production values and the presence of three members of the original cast, this is a long, tedious and curiously uneventful film. It has nothing new to say about environmental matters or unfettered science; themes that were front and centre in previous instalments. Nor does it do anything interesting with the main plot device of dinosaurs trying to integrate into our current ecosystems. But perhaps its biggest failing is the conspicuous lack of tension. The denizens of Jurassic World are simply not a threat and fail to have any emotional impact. The film doesn’t even placate viewers with superfluous cast members being eaten. The onscreen deaths by dinosaurs are rather tame.

Four years after dinosaurs escaped into the wider world, humans struggle to adapt to their presence. The US government has contracted BioSyn Genetics, to control the dinosaurs in a reserve based in Italy's Dolomite Mountains and to further research them for pharmaceutical purposes. Meanwhile in Nevada, Claire Dearing (Bryce Dallas Howard) and Owen Grady (Chris Pratt) do their best to protect the local dinosaur population and advocate for their humane treatment. They also care for 14-year-old Maisie Lockwood (Isabella Sermon), Benjamin Lockwood's biogenetic granddaughter. Maisie has become curious about her heritage and the fact that she was cloned from the scientist Charlotte Lockwood. Neither Claire or Owen are aware that the CEO of BioSyn, Lewis Dodgson (Campbell Scott), has designs on both Maisie and the velociraptor Blue, so he can further his genetic research. He hires mercenary Rainn Delacourt (Scott Haze) to kidnap both.

Jurassic World Dominion is not without a few good points. I was initially amused by the conceit of bringing back the character of Lewis Dodgson from the original movie, who is now the CEO of BioSyn, the main competitor to InGen. Sadly, the character doesn’t develop beyond being a two dimensional corporate bad guy. Which raises the question, are real life corporate bad guys “interesting”? The more I consider this the more I think not. The return of Sam Neil and Laura Dern sees a resumption of their “will they, won’t they” relationship. Dr. Ellie Sattler’s cosy family dynamic that we last saw in Jurassic Park III has now ended. There’s certainly still a spark between her and Dr. Alan Grant and it is fun to watch it rekindle. The return of Jeff Goldblum as Dr. Ian Malcolm is not so endearing and the character is trivialised to the status of a comic foil. As ever Michael Giacchino proves why he’s one of the best film composers around at present.

Director Colin Trevorrow does attempt to do several different things with the franchise formula. There’s a subplot about a thriving dinosaur blackmarket based in Malta. Owen and Claire attempt to infiltrate a sale only to be targeted by weaponized Atrociraptors that have been trained to kill. This culminates in a high speed chase through the narrow Maltese streets resulting in sub Bond/Jason Bourne shenanigans. It’s a curious change in style that doesn’t quite work. Then there is another storyline in which BioSyn creates genetically modified prehistoric locusts that eat everything apart from the company’s own copyrighted crops. It’s a superficially bold idea, again playing into existing evil corporation tropes but it simply doesn’t stand up to any scrutiny. Such a plan couldn’t be concealed and would quickly reveal that BioSyn was publicly holding the world to ransom.

Despite some potential promise, Jurassic World Dominion succumbs to the endemic failings of modern, mainstream, franchise filmmaking. The action scenes are loud, frenetic and rapidly edited yet devoid of any suspense. The visual effects are produced by a variety of companies and vary greatly in quality. The script is perfunctory, devoid of any charm and has nothing new to say. There are numerous nods and homages to Spielberg’s first instalment but all these do is highlight how well made the original film was and how superfluous the latest iteration is. Therein lies the flaw with popular franchise movies. Success begets ubiquity and ubiquity ultimately diminishes interest. However, the box office returns for Jurassic World: Dominion remain curiously high, indicating that the public still has an appetite for dinosaur based spectacle, irrespective of its narrative quality. I have no interest in a further instalment.

Update. Jurassic World Dominion has just been released on home media and includes the theatrical release of the film and an extended director’s edition which runs 14 minutes longer. As my review is based upon the cinema release I thought it fair to watch the longer version to see if it offers any significant improvement. The extended edition does provide a more coherent narrative and expands the role of Dr. Ellie Sattler. There’s a five minute prologue set in the Jurassic era, as well as an extra scene showing that there’s a history between Owen Grady and Rainn Delacourt. Naturally there are additional scenes of dinosaur based mayhem including something akin to a cockfight that takes place in the Maltese dinosaur black market. However, although the story is more coherent in the extended edition, it does not really impact upon the overall superfluous nature of Jurassic World Dominion. If you do decide to watch the film then choose the extended edition as it does iron out some of the flaws and is the better of the two versions.

Dear Mr. Watterson (2013)

Joel Allen Schroeder's documentary Dear Mr. Watterson is a curious beast insofar that it takes some time before it decides exactly what it wants to focus upon. It begins by examining the cultural impact of the hugely popular comic strip “Calvin & Hobbes” and what it means to people around the world. However, little information is given about the creator, Bill Watterson beyond a very simple biography. Joel Allen Schroeder’s also makes no attempt to contact and interview the reclusive Mr. Watterson to find out more about the man and his iconic work. Instead, the documentary eventually settles into an assessment of Watterson’s work by other industry luminaries and a broader accounting of the overall decline of the newspaper cartoon as a social institution. The presentation is bright, stylish and there’s a lot of love for the subject but it takes some time before it commits to a specific approach.

Joel Allen Schroeder's documentary Dear Mr. Watterson is a curious beast insofar that it takes some time before it decides exactly what it wants to focus upon. It begins by examining the cultural impact of the hugely popular comic strip “Calvin & Hobbes” and what it means to people around the world. However, little information is given about the creator, Bill Watterson beyond a very simple biography. Joel Allen Schroeder’s also makes no attempt to contact and interview the reclusive Mr. Watterson to find out more about the man and his iconic work. Instead, the documentary eventually settles into an assessment of Watterson’s work by other industry luminaries and a broader accounting of the overall decline of the newspaper cartoon as a social institution. The presentation is bright, stylish and there’s a lot of love for the subject but it takes some time before it commits to a specific approach.

Cartoonist Bill Watterson retired his comic strip “Calvin & Hobbes”, after a very successful ten year run from 1985 to 1995. The cartoon about a 6-year-old boy and his tiger companion, had and continues to have much to say about American culture, childhood, friendship and many other philosophical points. Although demonstrably a US product, its themes and characters had a worldwide appeal due to its universal themes. Furthermore, Watterson was extremely experimental in the way he presented his artwork, often abandoning the traditional linear panel format. What the documentary makes clear is that both Watterson and subsequently his cartoonist peers consider his creations “art”. The notion that the cartoon strip is an inherently lower form of artistic endeavour, is summarily dismissed as part of the inherent snobbery that exists around art per se. Watterson’s perspective on his own work is a key theme throughout the documentary.

Post 1995, Bill Watterson has led a reclusive life in small-town Ohio, where he has pursued other artistic endeavours. Although financially successful due to the ongoing syndication of “Calvin & Hobbes”, along with the continuous sales of anthologies of the cartoon, Watterson is notable as one of the few artists that has eschewed lucrative merchandising deals. Unlike most of his contemporaries such as Charles M. Schulz (“Peanuts”) and Jim Davis (“Garfield”). Dear Mr. Watterson takes a lot of pain to examine such an unusual stance, with one talking head hinting that it is borderline “unamerican” to do such a thing. Yet Watterson saw such monetisation as diminishing the artistic merits and significance of his creation. Something that Stephan Pastis, creator of “Pearls Before Swine” broadly agrees with, citing from personal experience that the moment you embrace marketing you are subject to a wealth of commercial pressures that impact upon your creativity.

Dear Mr. Watterson ultimately fall between two stools as it is a little too insular to be immediately accessible to those casually interested in “Calvin & Hobbes”, while simultaneously not being a definitive overview for hardcore fans. It does have its moments. One certainly gets a sense of Bill Watterson’s talent when looking at his original artwork at The Ohio State University. The documentary also does a good job of analysing the final cartoon he created which ends with the positive statement “Let’s go exploring”. It also accurately assesses the diminishing of comic strips in newspapers due to the industry's own decline. The conclusion is that it's highly unlikely that any other strip will achieve similar success and have such a cultural impact. “Calvin & Hobbes” remains an enigma born of great talent and the good fortune to be in the right place at the right time.

Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time (2021)

“Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time” is a sprawling, non-linear eulogy to the to the life of writer Kurt Vonnegut, by Emmy-winning director Robert B. Weide (“Curb Your Enthusiasm”), who was a friend of Vonnegut's throughout the last 25 years of his life. Weide himself features heavily throughout the two hour running time, which is something Weide says he usually hates in documentaries. However, what unfolds is a story of a documentary maker who wanted to film his idol and was granted an opportunity to do so in the early eighties. The project was never completed and both Weide and Vonnegut continuously returned to it over the years as their friendship grew, leading to Weide eventually becoming Vonnegut’s personal archivist. However, despite this curious relationship, this is still very much a film about Kurt Vonnegut, the author, the social commentator and the man. It becomes quite clear why he is considered one of the most important writers of the 20th century.

“Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time” is a sprawling, non-linear eulogy to the to the life of writer Kurt Vonnegut, by Emmy-winning director Robert B. Weide (“Curb Your Enthusiasm”), who was a friend of Vonnegut's throughout the last 25 years of his life. Weide himself features heavily throughout the two hour running time, which is something Weide says he usually hates in documentaries. However, what unfolds is a story of a documentary maker who wanted to film his idol and was granted an opportunity to do so in the early eighties. The project was never completed and both Weide and Vonnegut continuously returned to it over the years as their friendship grew, leading to Weide eventually becoming Vonnegut’s personal archivist. However, despite this curious relationship, this is still very much a film about Kurt Vonnegut, the author, the social commentator and the man. It becomes quite clear why he is considered one of the most important writers of the 20th century.

“Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time” is structured very much like Vonnegut's writing; deliberately fragmented and very self-aware. At times it takes a chronological approach and at others, leaps forward to future events and highlights this by showing Weide editing the very documentary on his computer. We do get to learn about Vonnegut’s youth, family and other key aspects of his life as the documentary lapses into a classic PBS approach to its subject. It takes a while to get to the matter of his experiences in Dresden in World War II and despite his irreverent tone, it is clear that this part of his life is key to his mindset and philosophy in later life, as well as his emotional well being. All of which paints a very interesting and broadly favourable portrait of the man. Which makes it all the more jarring when he leaves his wife shortly after achieving the success in which her support is instrumental.

Where “Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time” excels is in examining the wealth of material regarding Vonnegut’s writing. We see first draft, typewritten manuscripts complete with handwritten revisions that clearly show the author refining his style and process during his early years. Correspondence and then later, answerphone messages provide further insight to the author’s struggle to commit his work to the page and the birth of his alter ego, Kilgore Trout. As the documentary progresses, over time Vonnegut becomes very comfortable talking about himself to Weide. He clearly shows he is someone who relishes his relationship with his audience and the opportunity to “perform”. There is some compelling footage of talks and lectures in which Vonnegut effortlessly engages with fans and riffs off their questions and adulation. Not every author requires the love of his readers but it clearly was integral to Vonnegut’s pathology.

Overall, any gaps in the history of Kurt Vonnegut or self-indulgent asides are subordinate to this documentary’s sincere and honest analysis of Vonnegut's World War II experiences. His initial denial of the significance of his time as a P.O.W. is ultimately overturned after writing “Slaughterhouse Five” and the documentary takes great pains to stress the cathartic nature of this undertaking. His disgust of war subsequently boiled over again during the second Bush administration and the subsequent invasion of Iraq. Vonnegut despised the use of patriotism as a political tool and subsequently wrote a series of opinion pieces for “In These Times” magazine which became the foundation for his final major work “A Man Without a Country”. Robert B. Weide’s ““Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time”” is a loving tribute to a dear friend as well as an analysis of a cultural icon. It’s important to appreciate the former while addressing the latter. There may well be future documentaries about Vonnegut that are more objective but they’ll not be as personal as this one.

Murphy's War (1971)

During the last days of World War II, the British Merchant Navy ship Mount Kyle is torpedoed by a German U-Boat off the coast of Venezuela. The crew are subsequently massacred as they abandon ship, leaving one survivor, an Irish engineer named Murphy (Peter O’Toole). After being rescued by Louis Brezon (Philippe Noiret), a caretaker for an oil company which has a pipeline in the area, he is taken to a local missionary medical facility run by Dr. Hayden (Siân Phillips). Upon recovering, Murphy becomes determined to find the U-Boat that sank his ship and seeks revenge. However, as the war is clearly drawing to a close Dr. Hayden is reluctant to help him and tries to dissuade him from his plan as it may endanger the local community. In the meantime, Murphy finds a damaged Grumman J2F Duck floatplane from his ship and salvages it. With the assistance of Louis, he makes some improvised munitions and draws his plans against the Germans.

During the last days of World War II, the British Merchant Navy ship Mount Kyle is torpedoed by a German U-Boat off the coast of Venezuela. The crew are subsequently massacred as they abandon ship, leaving one survivor, an Irish engineer named Murphy (Peter O’Toole). After being rescued by Louis Brezon (Philippe Noiret), a caretaker for an oil company which has a pipeline in the area, he is taken to a local missionary medical facility run by Dr. Hayden (Siân Phillips). Upon recovering, Murphy becomes determined to find the U-Boat that sank his ship and seeks revenge. However, as the war is clearly drawing to a close Dr. Hayden is reluctant to help him and tries to dissuade him from his plan as it may endanger the local community. In the meantime, Murphy finds a damaged Grumman J2F Duck floatplane from his ship and salvages it. With the assistance of Louis, he makes some improvised munitions and draws his plans against the Germans.

I suspect that Murphy’s War was intended to be a minimalist exploration of the old adage “if you devote your life to seeking revenge, first dig two graves”. Written by Stirling Silliphant (The Enforcer, Towering Inferno) and directed by Peter Yates (Bullitt, The Deep and Krull), Murphy’s War teases the audience with several instances of potential narrative depths. What motivates U-Boat Commander Lauchs (Horst Janson) to shoot the crew of the Mount Kyle, as they pose no threat to him or his vessel? Is there a love triangle between Murphy, Dr. Hayden and Louis? Why is Murphy so motivated to destroy the U-Boat, considering he initially comes across as a reluctant seaman with little love for English Officers. There’s even a tenuous reference to the IRA. Is he deranged or honourable? These questions raise some interesting opportunities for the film to explore some timeless cinematic themes.

Sadly, even within the deliberately understated framework of seventies cinema, these elements are woefully neglected, leaving us with a matter of fact story that struggles to fill its 106 minutes running time. It’s all somewhat ponderous and very frustrating when considering the quality of the cast and production. Hence we have lengthy scenes in which Murphy struggles to fly the salvaged seaplane and then later, flying around the Orinoco River searching for his quarry. It’s all beautifully shot by veteran cinematographer, Douglas Slocombe, but it often feels like padding to bolster a story that isn’t anywhere near as deep as it likes to think. The climax of the film and Murphy’s subsequent Pyrrhic victory lacks any dramatic impact because there’s no explanation for his descent into a latter day Captain Ahab. The audience is left to ponder whether it was all worthwhile and I for one, broadly feel that it wasn’t. Considering the pedigree of this production, Murphy’s War should be much better.

Ennio (2021)

Giuseppe Tornatore’s sprawling documentary Ennio, is a finely detailed and absorbing exploration of prolific and iconic Italian composer Ennio Morricone. Despite its very traditional approach to its subject matter, looking at Morricone’s career chronologically, intercut with celebrity talking heads, it still manages to convey the unorthodox, innovative and experimental nature of the composer. The 156 minute running time is not necessarily the impediment that one expects. Rather it is the sheer weight of the emotional impact that comes from Morricone’s music that is at times overwhelming. Archival footage and a new and comprehensive interview recorded just prior to the composer’s death in 2020 is intercut with a wealth of audio cues and concert footage from a broad cross section of his work. The result is most illuminating with regard to the man and his approach to composing. The conclusion backed by many of those interviewed is that Ennio Morricone has shaped the nature of film music and elevated it to an artform.

Giuseppe Tornatore’s sprawling documentary Ennio, is a finely detailed and absorbing exploration of prolific and iconic Italian composer Ennio Morricone. Despite its very traditional approach to its subject matter, looking at Morricone’s career chronologically, intercut with celebrity talking heads, it still manages to convey the unorthodox, innovative and experimental nature of the composer. The 156 minute running time is not necessarily the impediment that one expects. Rather it is the sheer weight of the emotional impact that comes from Morricone’s music that is at times overwhelming. Archival footage and a new and comprehensive interview recorded just prior to the composer’s death in 2020 is intercut with a wealth of audio cues and concert footage from a broad cross section of his work. The result is most illuminating with regard to the man and his approach to composing. The conclusion backed by many of those interviewed is that Ennio Morricone has shaped the nature of film music and elevated it to an artform.

Morricone’s personal recollections of his youth and of his family’s poverty are candid. His Father, a trumpet player of some note, insisted his son learn music as a means to “put food on the table”. Morricone’s skill took him to the Saint Cecilia Conservatory to take trumpet lessons under the guidance of Umberto Semproni. He then went on to study composition, and choral music under the direction of Goffredo Petrassi. However, despite this very formal music education, Morricone took an innovative approach to his arrangements and would often use unorthodox sounds to add character to his work. During his tenure at RCA Victor as senior studio arranger, his contemporary approach found him working with such artists as Renato Rascel, Rita Pavone and Mario Lanza. As his reputation subsequently grew, composing for film became a logical and practical career progression. However, this was something that was looked down on by his more formal colleagues. A view that changed overtime as the calibre of his work became undeniable.

Ennio features a wealth of soundbites from prior interviews and new ones, from old friends, fellow musicians and admirers. Some are profound, some gush and others are curious by sheer dint of their inclusion. The views of Bruce Springsteen are somewhat hyperbolic and Paul Simonon makes a single obvious statement. However the insight we gain from classical composer Boris Porena is extremely thoughtful and interesting. As are the views of Hans Zimmer and Mychael Danna. There are also numerous personal anecdotes from assorted collaborators, including Joan Baez, Paolo and Vittorio Taviani as well as Roland Joffé. Baez recalls how Morricone intuitively wrote for her entire vocal range. The Taviani brothers reflected upon how they were at odds with the maestro only to be totally won over by work. Joffé reflects how Morricone wept when he saw The Mission, stating it didn’t need a score. Often it is Morricone’s own recollections that are the most intriguing. For someone of such exceptional talent he remains grounded, sincere and protective of his craft.

Director Giuseppe Tornatore naturally focuses on his own collaborations with Morricone, especially Cinema Paradiso, but overall Ennio is about the man, his philosophy and his joy of music. Some critics have inferred that this documentary is too Italian-centric but that is a crass complaint. Sixty years of Italian culture, both artistically and politically, are reflected in Morricone’s work. Hence there is significance in the reminiscences of Italian pop stars contracted to RCA who owe their success to Morricone’s innovative arrangements and production values. Ennio also features several anecdotes that are surprising and revealing, such as how the maestro missed an opportunity to write the soundtrack for Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Long and at times a little overwhelming, Ennio is a fitting tribute to the great composer. It is also a testament to the skills of editor Massimo Quaglia for cogently assembling such a vast amount of information and sentiment into a coherent narrative.

Classic Movie Themes: Star Trek First Contact

Jerry Goldsmith’s contribution to Star Trek is immense. Yet simply listing the films and TV episodes he wrote music for does not adequately encapsulate the significance of his contribution to the franchise. His majestic, thoughtful and uplifting musical scores provide an emotional foundation that reflects the core ethos of Star Trek. They also create an invaluable sense of continuity that spans multiple shows and movies. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is his iconic title music for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) that was subsequently adopted as the theme tune for Star Trek: The Next Generation. His work was held in such high regard, when Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989) ran into production issues, it was thought that a Jerry Goldsmith soundtrack may well elevate the film. Sadly it didn’t but his work on that instalment was outstanding and among his best.

Jerry Goldsmith’s contribution to Star Trek is immense. Yet simply listing the films and TV episodes he wrote music for does not adequately encapsulate the significance of his contribution to the franchise. His majestic, thoughtful and uplifting musical scores provide an emotional foundation that reflects the core ethos of Star Trek. They also create an invaluable sense of continuity that spans multiple shows and movies. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is his iconic title music for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) that was subsequently adopted as the theme tune for Star Trek: The Next Generation. His work was held in such high regard, when Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989) ran into production issues, it was thought that a Jerry Goldsmith soundtrack may well elevate the film. Sadly it didn’t but his work on that instalment was outstanding and among his best.

Jerry Goldsmith returned to the franchise in 1995, writing the dignified and portentous Star Trek: Voyager theme. Again this succinctly showed the importance the producer’s of the franchise attached to his work. Then in 1996 Goldsmith wrote the score for Star Trek: First Contact. Again his music demonstrates his ability to imbue the film’s narrative themes and visual effects with an appropriate sense of awe and majesty. Although contemporary in his outlook, with an inherent ability to stay current, Goldsmith had studied with some of the finest composers from the golden age of Hollywood. Hence, there are a few cues from First Contact where the influence of the great Miklós Rózsa are quite apparent and beautifully realised. Fans will argue that his score for Star Trek: The Motion Picture is his greatest work in relation to the franchise but I think that the soundtrack for Star Trek: First Contact has more emotional content.

The track “First Contact” which comes at the climax of the film is in many ways the highlight of the entire score. Goldsmith uses English and French horns as Picard and Data reflect upon the nature of temptation after defeating the Borg Queen. When the alien vessel lands and its crew disembarks to make first contact, the melody takes on a profoundly ethereal and even religious quality, especially when the church organ reiterates the theme. This reaches a triumphant peak when it is revealed that the first visitors to Earth are Vulcan. The cue then takes a melancholy turn as Picard and Lily bid a touching farewell. “First Contact” is a sublime six minutes and four seconds which demonstrates why Jerry Goldsmith was such a superb and varied composer. It not only highlights his legacy to Star Trek but also his status as one of the best film composers of his generation.

Complex Lore and Enigmatic Themes

I recently watched the first trailer for the new Obi-Wan Kenobi television show that is premiering on Disney + in May. I am interested in this latest instalment in the Star Wars franchise and curious as to whether Liam Neeson will make an appearance. I also watched a 20 minute fan video in which they “analysed” the entire trailer. They discussed the content of this 2 minute preview and then did a great deal of speculating about potential themes and characters that may feature in the show. They were clearly enthusiastic about what they had seen and were very knowledgeable about the subject. This resonated with me, as I like to be well versed about the things I enjoy. However, it is worth remembering that fandom can tip into obsession and gatekeeping. Hence I feel there is a subject to explore here.

I recently watched the first trailer for the new Obi-Wan Kenobi television show that is premiering on Disney + in May. I am interested in this latest instalment in the Star Wars franchise and curious as to whether Liam Neeson will make an appearance. I also watched a 20 minute fan video in which they “analysed” the entire trailer. They discussed the content of this 2 minute preview and then did a great deal of speculating about potential themes and characters that may feature in the show. They were clearly enthusiastic about what they had seen and were very knowledgeable about the subject. This resonated with me, as I like to be well versed about the things I enjoy. However, it is worth remembering that fandom can tip into obsession and gatekeeping. Hence I feel there is a subject to explore here.

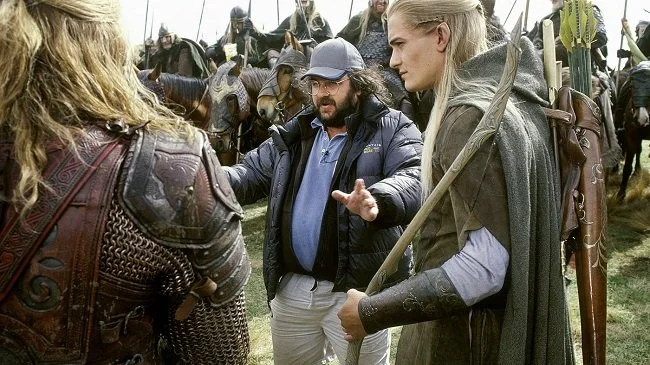

Fantasy, science fiction and similar hybrid genres thrive on world building and lore. These facets give them credibility and breathe life into fictional worlds and people. They also provide parallels with our own lives which provides a means for us to connect to them. Star Wars, despite all the technology, offers a universe that looks used and lived in. Middle-earth is steeped in history and complex societies. Again despite obvious differences there are commonalities in the hierarchies, rituals and personal aspirations of the protagonists. And as well as lore, there are also enigmas. Fantasy and science fiction are often rife with things that are strange and ill defined. Often these are mystical and symbolic. The Force, Tom Bombadil and Jason Voorhees are prime examples of this. Successful fantasy and science fiction find the right balance between detailed lore and enigmatic themes.

Achieving this balance is very difficult. The original Star Wars trilogy handled the arcane and esoteric nature of the Force well. It was broadly defined as an energy field created by all life that connected everything in the universe. However, the specifics of this were vague and nebulous which played well with the concept that the Jedi were more of a religious and philosophical order than a paramilitary organisation. However, when the prequels introduced the concept of Midi-chlorians it somewhat diminished the enigma surrounding the Force and it suddenly just became yet more technobabble. It is interesting to note that this addition to the franchise’s lore was not well received by fans. It was subsequently not alluded to in later films and television shows, indicating that the producers and writers felt it was a mistake.

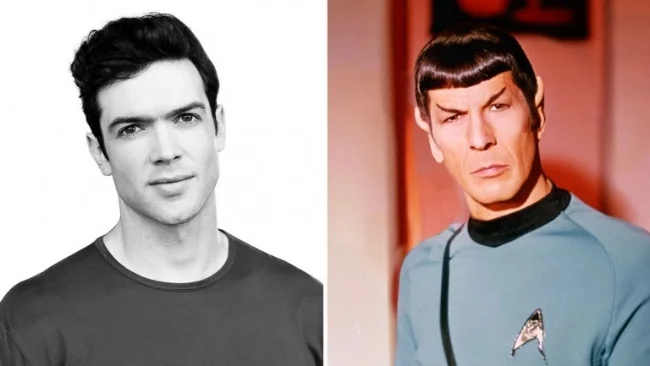

Another genre example of lore versus enigma is the difference in Klingon anatomy between the original series and the revival shows. The main reason is simple. There wasn’t a budget for complex prosthetics in the sixties show. However, from Star Trek: The Motion Picture onwards, Klingons acquired their forehead ridges as a way to make them more alien. This however left a lore contradiction, which was beautifully alluded to in the episode “Trials and Tribble-ations” of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Several crew members from the 24th century including Worf, find themselves on Deep Space Station K7 in the 23rd century, during the events of “Trouble with Tribbles”. Upon seeing the Klingons from the previous era, one of the crew asks Worf why there’s a physical difference. He enigmatically replies “We do not discuss it with outsiders”. This beautifully vague but droll answer works perfectly. Sadly it was ruined a few years later when an episode of Star Trek: Enterprise explained away the difference as a genetic experiment that went wrong.

However, it is not always an excess of lore that can quash the soul from a popular show or film. Sometimes being deliberately too vague, refusing to expedite the plot and simply replacing one mystery with two others can be very frustrating. It may also be due to the writers being out of their depth or making things up as they go along. Lost encapsulated this for me and the show’s manipulative narrative quickly killed my interest. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t like to be spoon fed stories and explanations and I don’t mind thinking when watching. The ending of John Carpenter’s The Thing is enigmatic and quite bleak but I consider it a perfect conclusion to the film. However, perhaps the television show that really stepped over the line for not making any real effort to explain itself and turning the enigma “up to 11” is The Prisoner. It’s still a great show to watch and is very thought provoking but the final episode doesn’t deliver a stone cold conclusion. Something that people who watched it originally still seethe over.

We live in a culture of binge watching TV shows which some viewers dissect and analyse. The interconnected nature of the Marvel Cinematic Universe is a prime example of this and it does it extremely well. But not all television shows and films are like this and do not require such scrutiny. I worry that some viewers are so invested in searching for what they think may be hidden or trying to pre-empt an unfolding narrative, that they miss being in the moment and simply enjoying the show as it happens. Excessive analysis often leads to disappointment. It is important to remember that what you’re watching is a writer(s) thoughts on how a narrative should move forward. They are not obliged to try to make what’s in your or my head. Therefore I see both lore and enigmatic themes as an embellishment to a good fantasy or science fiction show or film. Things to be enjoyed but not the “be-all and end-all” of the production. If either becomes the major focus of either the writers or fans then it will end up undermining the central narrative and themes.

The King's Man (2021)

As a collection of history's worst tyrants and criminal masterminds gather to plot a war to wipe out millions, one man must race against time to stop them. Discover the origins of the very first independent intelligence agency in The King's Man. Based on the Comic Book “The Secret Service” by Mark Millar and Dave Gibbons. 20th Century Studios

Matthew Vaughn’s The King’s Man is an inconsistent film, both narratively and tonally. It veers between serious themes and stylised, hyperbolic action. At times it does quite a good job of exploring such complex subjects as global politics, mechanised warfare and colonialism. Sadly it then wrenches the viewer out of these cerebral reveries as it lapses into the sort of over the top action sequences that were notable in the two earlier films. It’s a shame because The King’s Man gets so many other aspects of the production right. The casting is very interesting, especially Ralph Fiennes as the “pacifist” Duke of Oxford. He is actually a very good fit for the action genre. Djimon Hounsou and Gemma Arterton are given little backstory beyond being respectively the faithful manservant and the family nanny but both are notable due to their own inherent acting chops and personal charisma. Rhys Ifans obviously has a great time as Grigori Rasputin, ensuring all the man’s vices are robustly depicted.

As a collection of history's worst tyrants and criminal masterminds gather to plot a war to wipe out millions, one man must race against time to stop them. Discover the origins of the very first independent intelligence agency in The King's Man. Based on the Comic Book “The Secret Service” by Mark Millar and Dave Gibbons. 20th Century Studios

Matthew Vaughn’s The King’s Man is an inconsistent film, both narratively and tonally. It veers between serious themes and stylised, hyperbolic action. At times it does quite a good job of exploring such complex subjects as global politics, mechanised warfare and colonialism. Sadly it then wrenches the viewer out of these cerebral reveries as it lapses into the sort of over the top action sequences that were notable in the two earlier films. It’s a shame because The King’s Man gets so many other aspects of the production right. The casting is very interesting, especially Ralph Fiennes as the “pacifist” Duke of Oxford. He is actually a very good fit for the action genre. Djimon Hounsou and Gemma Arterton are given little backstory beyond being respectively the faithful manservant and the family nanny but both are notable due to their own inherent acting chops and personal charisma. Rhys Ifans obviously has a great time as Grigori Rasputin, ensuring all the man’s vices are robustly depicted.

The problem lies with The King’s Man essentially trying to do too much and cover too much ground in its 130 minute running time. First it’s a father-son film and then it’s a revisionist history drama like Trantino’s Inglourious Basterds. Then it hastily tries to establish the backstory of the Kingsman Independent Intelligence Service. As a result director Matthew Vaughn struggles to maintain a consistent style and tone. He does provide some creative flourishes especially with the subplot relating to Conrad Oxford, the Duke’s son who wishes to serve his country and play his part in World War I. There is a sense of impending doom as Conrad (Harris Dickinson) heads towards an inevitable personal tragedy but the way it manifests itself is quite a surprise. This culminates in a genuinely moving scene at the end of the film’s second act. However, it is quickly mitigated by the directors interpretation of historical events and choosing to depict the tragedy and slaughter of WW I as a petty squabble between an international family.

The King’s Man is certainly a better film than its predecessor; Kingsman: The Golden Circle (2017). That was a poorly conceived project, ruined by the presence of Eltom John and the mean spirited way in which Merlin (Mark Strong) was so ignominiously killed off. Although Matthew Vaughn is clearly a creative film director who has a natural affinity to genre source material, he does strike me as someone who would be well served by a trusted associate who knows him well enough to curb his excesses. Both previous films in this series were blighted by some singularly unpalatable and obsolete sexual humour that would be more at home in a seventies “eroitic adventure” such as Confessions of a Window Cleaner. This error is not repeated in The King’s Man but instead Vaughn often comes a little too close to trivialising the human tragedy of WWI. There’s also a mid-credit coda that is very ill judged, especially in light of more recent events. Watch with discretion and be prepared to “hold your nose” if you are overly politically sensitive. The action is good.

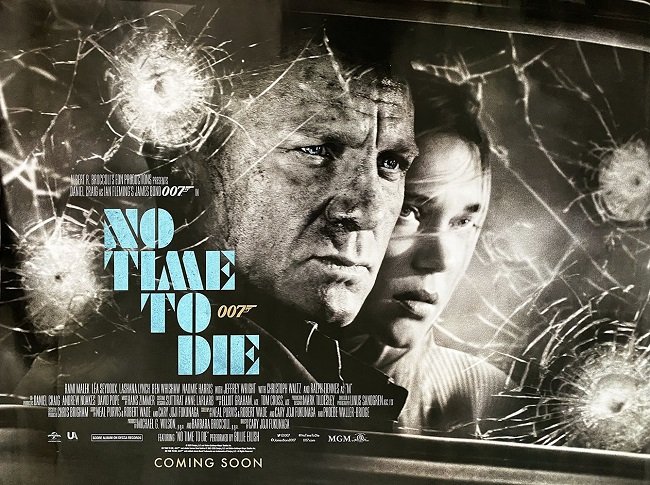

No Time to Die (2021)

Bond has left active service and is enjoying a tranquil life in Jamaica. His peace is short-lived when his old friend Felix Leiter from the CIA turns up asking for help. The mission to rescue a kidnapped scientist turns out to be far more treacherous than expected, leading Bond onto the trail of a mysterious villain armed with dangerous new technology.

Universal Pictures

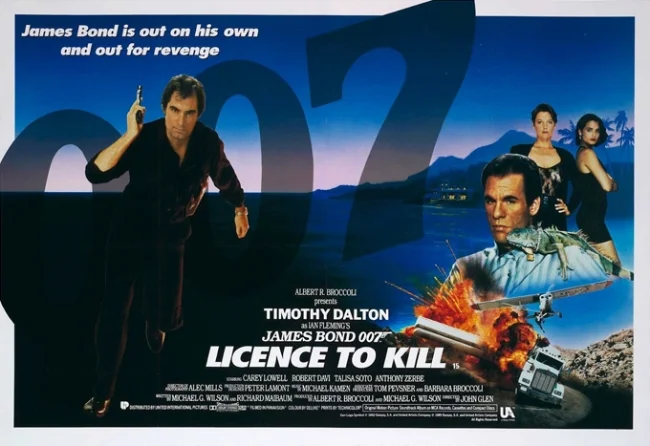

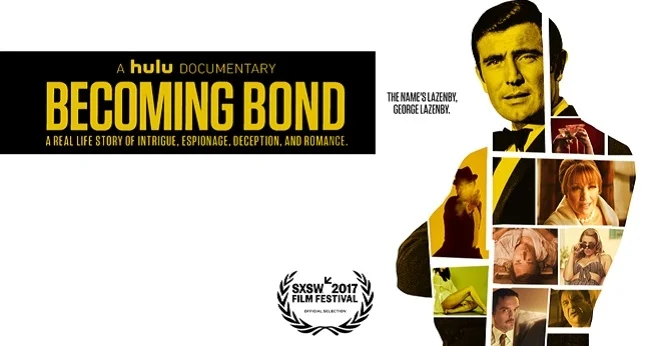

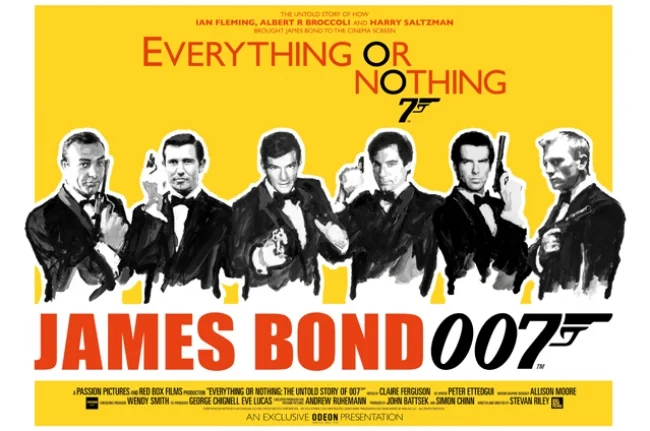

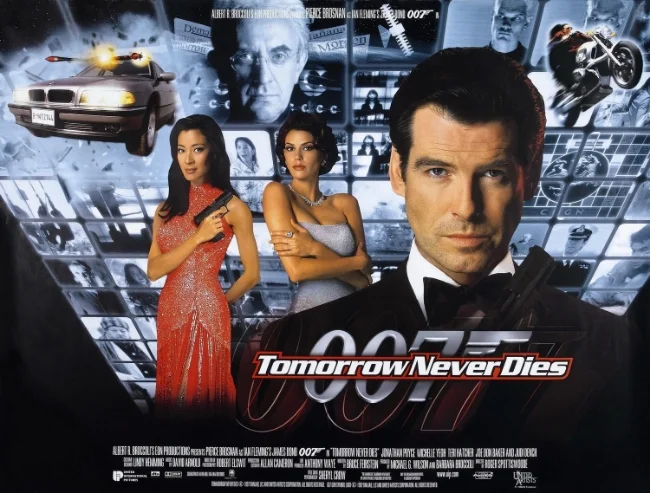

The twenty fifth Bond film is a horse of a different colour but then again that adage could be applied to the last five instalments of the franchise. Bond has never had a continuous story arc or any major narrative continuity until Daniel Craig’s tenure as 007. Two Roger Moore films briefly alluded to Bond’s previous marriage as depicted in On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969). However, we should remember that Casino Royale (2006) was effectively a reboot of the entire franchise depicting Bond’s first mission as a recently commissioned 00 agent. As well as the tonal shift in the franchise regarding humour, violence and the role of agents in a modern world, the last five films have taken a far more personal interest into Bond. It has very much been about him as opposed to just his actions. Therein lies the rub as they say. Some fans have not warmed to this sort of character analysis, although the box office clearly shows that it has gone down well with the wider audience.