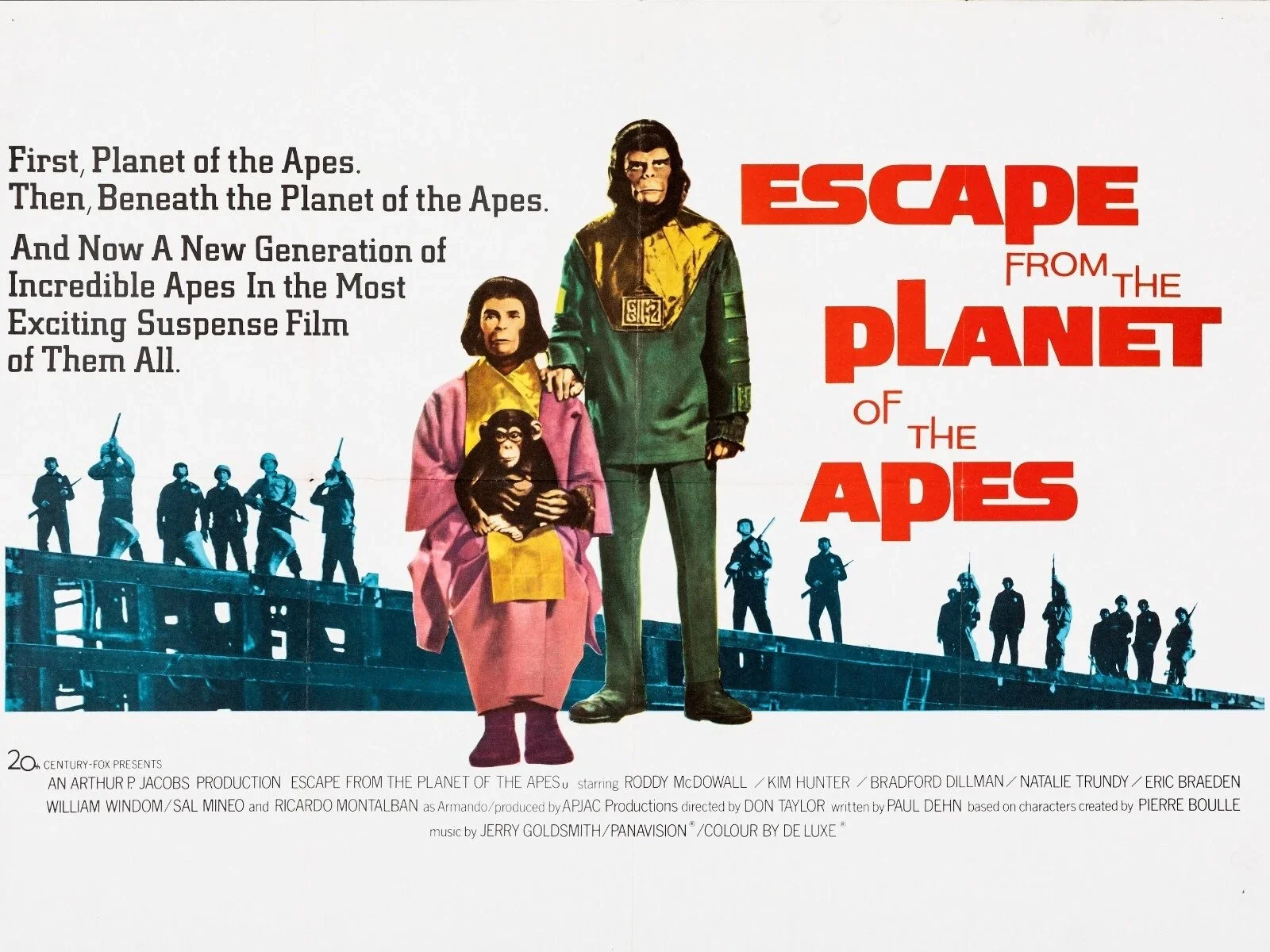

Classic Movie Themes: Escape from the Planet of the Apes

The Planet of the Apes movie franchise took a radical change of course with its third entry in the series. The first two films were set in the future and benefited from high production values to help realise a post apocalyptic earth. However, due to a substantial reduction of budget, Escape from the Planet of the Apes uses a time travel plot device to bring the ape protagonists to present day Los Angeles (1971 in this case). The result is a film with a much smaller narrative scope. However, although it lacks the science fiction spectacle of its predecessors, it features an interesting satirical exploration of celebrity culture and ponders what it is like to be deemed an enemy of the state. As ever, Roddy McDowell and Kim Hunter provide exceptional lead performances as the Chimpanzees Cornelius and Zira. Escape from the Planet of the Apes also captures the pop culture vibe of seventies America.

The Planet of the Apes movie franchise took a radical change of course with its third entry in the series. The first two films were set in the future and benefited from high production values to help realise a post apocalyptic earth. However, due to a substantial reduction of budget, Escape from the Planet of the Apes uses a time travel plot device to bring the ape protagonists to present day Los Angeles (1971 in this case). The result is a film with a much smaller narrative scope. However, although it lacks the science fiction spectacle of its predecessors, it features an interesting satirical exploration of celebrity culture and ponders what it is like to be deemed an enemy of the state. As ever, Roddy McDowell and Kim Hunter provide exceptional lead performances as the Chimpanzees Cornelius and Zira. Escape from the Planet of the Apes also captures the pop culture vibe of seventies America.

The soundtrack for Escape from the Planet of the Apes, marked the return of composer Jerry Goldsmith, whose score for Planet of the Ape had been nominated for an Oscar. On this occasion Goldsmith shifts from the stark, avant-garde style of the first film, to a lighter, more upbeat seventies sound, reflecting the film’s comedic and romantic elements. However, Goldsmith still maintains his signature use of unconventional percussion, brass, and innovative orchestral techniques. The result is a unique, fun and charming score which despite being very much of the time, does a great deal to bolster the unfolding drama. The title theme stands out with its unusual time signature and rhythmic bassline, played by the legendary session musician Carol Kaye. Goldsmith also uses both sitar and steel drums adding to the quirky character of the piece.

Despite the lighter tone of Jerry Goldsmith’s soundtrack, Escape from the Planet of the Apes is a very bleak film with respect to its ending, which features infanticide. Musically, unlike the oppressive dread of the Planet of the Ape, the score for this film embraces the musical informality of the early seventies. The cue “Shopping Spree” captures the romantic interactions between Cornelius and Zira, incorporating charming piano melodies. While tracks such as “The Hunt” offer moments of suspense and are written in a more traditional idiom. However, the main title theme for the film remains the stand out track and is presented here for your enjoyment. It remains a prime example of the inherent versatility of composer Jerry Goldsmith who on this occasion goes for a more pop infused approach to his writing. The result is a charismatic soundtrack that captures the essence of the film and the mood of the time.

The Final Conflict (1981)

As a rule, it is always a challenge to end a trilogy of films successfully. Writing a satisfying denouement to a standalone movie is hard enough. To be able to conclude all pertinent story arcs and themes that have been sustained over three feature films, to everyone’s liking is far harder to achieve. In the case of The Final Conflict (1981), the last instalment of The Omen trilogy, writer Andrew Birkin does manage to resolve all of the external, internal and philosophical stakes, which are the fundamental components of a cinematic screenplay. Unfortunately, it is done in an incredibly underwhelming manner, which left audiences feeling cheated. The last time good defeated evil evil in such an unspectacular fashion was in Hammer’s To the Devil a Daughter (1976). This is why, in spite of solid production values, The Final Conflict is the least popular of the films about the Antichrist, Damien Thorn.

As a rule, it is always a challenge to end a trilogy of films successfully. Writing a satisfying denouement to a standalone movie is hard enough. To be able to conclude all pertinent story arcs and themes that have been sustained over three feature films, to everyone’s liking is far harder to achieve. In the case of The Final Conflict (1981), the last instalment of The Omen trilogy, writer Andrew Birkin does manage to resolve all of the external, internal and philosophical stakes, which are the fundamental components of a cinematic screenplay. Unfortunately, it is done in an incredibly underwhelming manner, which left audiences feeling cheated. The last time good defeated evil evil in such an unspectacular fashion was in Hammer’s To the Devil a Daughter (1976). This is why, in spite of solid production values, The Final Conflict is the least popular of the films about the Antichrist, Damien Thorn.

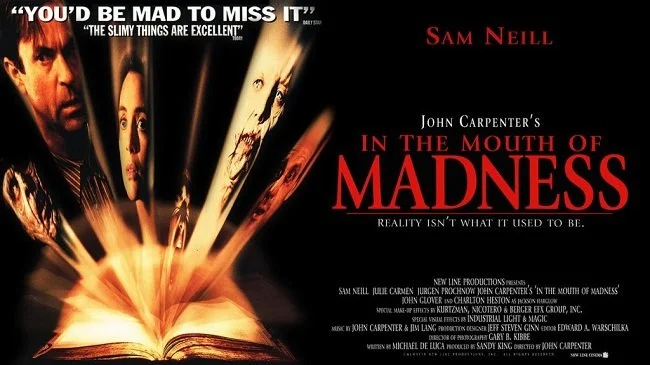

Damien Thorn (Sam Neill), is now 32 years old and head of his late uncle's international conglomerate, Thorn Industries. The US president appoints him Ambassador to Great Britain, which Thorn reluctantly accepts on the condition he also becomes head of the UN Youth Council. Thorn moves to the UK and continues his international scheming. However, an alignment of the stars heralds the Second Coming of Christ who, according to scripture, is to be born in England. Thorn subsequently orders all boys in the country born during the alignment to be killed. Meanwhile, Father DeCarlo (Rossano Brazzi) and six other priests recover the seven daggers of Megiddo, the only holy artefacts that can kill the Antichrist. They seek to hunt Thorn in the hope of killing him before he can destroy the Christ-child. But when the first assassin attempt goes awry, Thorn becomes aware of their plans.

The Final Conflict benefits greatly from the casting of Sam Neil as Damien Thorn. He is suitably charming and brooding. Filmed mainly in the UK, the production values are high and the film uses such locations as Cornwall and North Yorkshire extremely well. The cinematography is handled by Phil Meheux and Robert Paynter, who were both stalwarts of the UK film industry at the time. Jerry Goldsmith’s score is magnificent and does much of the heavy lifting, adding a sense of gravitas and gothic dread. The screenplay includes some bold ideas with themes of political manipulation by Thorn industries, as they create the very environmental disasters that they subsequently supply aid to. Director Graham Baker does not shy away from the infanticides ordered by Damien Thorn. Although not explicit, it is a disturbing aspect of the story.

Yet, despite so many positive points, The Final Conflict runs out of steam after the first hour. Too many good ideas are not developed sufficiently. The international intrigue alluded to at boardroom level, takes place off screen. The film would have been substantially improved if we saw directly Damien Thorn travelling the world and engaging with refugees and becoming a champion of the people. Including international locations would have better conveyed his global reach. Damien also doesn’t get to spar with his adversary. Instead he berates and harangues Christ via a rather disturbing full size crucifix that he keeps locked in an attic. Perhaps the biggest mistake the film makes is with the extravagant and contrived set pieces that befall those who discover Damien Thorn’s true nature. These had become a hallmark of the franchise. The first two onscreen deaths work well but the rest fall somewhat flat and simply aren’t shocking enough. As for ending, it serves its purpose but nothing more.

Overall, The Final Conflict is a well made but disappointing conclusion to what was originally a very intriguing franchise. Perhaps with a larger budget and a broader narrative scope that made the story more international, it could have fulfilled its potential. It certainly should have been more ambitious with its death scenes as its two predecessors were. Sadly instead of a decapitation with a sheet of glass or bisection by a lift cable, we have to make do with a high fall from a viaduct and a couple of stabbings. And then there’s the underwhelming ending. The more you think about it, the more you wonder how the studio thought this would be an appropriate ending. As it stands, The Final Conflict is watchable but offers nothing more than a perfunctory ending to the story of the rise and fall of Antichrist, Damien Thorn. Adjust your expectations accordingly.

Classic Movie Themes: Star Trek First Contact

Jerry Goldsmith’s contribution to Star Trek is immense. Yet simply listing the films and TV episodes he wrote music for does not adequately encapsulate the significance of his contribution to the franchise. His majestic, thoughtful and uplifting musical scores provide an emotional foundation that reflects the core ethos of Star Trek. They also create an invaluable sense of continuity that spans multiple shows and movies. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is his iconic title music for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) that was subsequently adopted as the theme tune for Star Trek: The Next Generation. His work was held in such high regard, when Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989) ran into production issues, it was thought that a Jerry Goldsmith soundtrack may well elevate the film. Sadly it didn’t but his work on that instalment was outstanding and among his best.

Jerry Goldsmith’s contribution to Star Trek is immense. Yet simply listing the films and TV episodes he wrote music for does not adequately encapsulate the significance of his contribution to the franchise. His majestic, thoughtful and uplifting musical scores provide an emotional foundation that reflects the core ethos of Star Trek. They also create an invaluable sense of continuity that spans multiple shows and movies. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is his iconic title music for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) that was subsequently adopted as the theme tune for Star Trek: The Next Generation. His work was held in such high regard, when Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989) ran into production issues, it was thought that a Jerry Goldsmith soundtrack may well elevate the film. Sadly it didn’t but his work on that instalment was outstanding and among his best.

Jerry Goldsmith returned to the franchise in 1995, writing the dignified and portentous Star Trek: Voyager theme. Again this succinctly showed the importance the producer’s of the franchise attached to his work. Then in 1996 Goldsmith wrote the score for Star Trek: First Contact. Again his music demonstrates his ability to imbue the film’s narrative themes and visual effects with an appropriate sense of awe and majesty. Although contemporary in his outlook, with an inherent ability to stay current, Goldsmith had studied with some of the finest composers from the golden age of Hollywood. Hence, there are a few cues from First Contact where the influence of the great Miklós Rózsa are quite apparent and beautifully realised. Fans will argue that his score for Star Trek: The Motion Picture is his greatest work in relation to the franchise but I think that the soundtrack for Star Trek: First Contact has more emotional content.

The track “First Contact” which comes at the climax of the film is in many ways the highlight of the entire score. Goldsmith uses English and French horns as Picard and Data reflect upon the nature of temptation after defeating the Borg Queen. When the alien vessel lands and its crew disembarks to make first contact, the melody takes on a profoundly ethereal and even religious quality, especially when the church organ reiterates the theme. This reaches a triumphant peak when it is revealed that the first visitors to Earth are Vulcan. The cue then takes a melancholy turn as Picard and Lily bid a touching farewell. “First Contact” is a sublime six minutes and four seconds which demonstrates why Jerry Goldsmith was such a superb and varied composer. It not only highlights his legacy to Star Trek but also his status as one of the best film composers of his generation.

Classic Movie Themes: Alien

Alien is a unique genre milestone. It challenged the established aesthetic created by 2001: A Space Odyssey of space travel being pristine, clinical and high tech and replaced it with a grimy, industrial quality. The space tug Nostromo is also a conspicuously “blue collar”, civilian venture, underwritten by a large corporation. As for H. R Giger’s xenomorph, it redefined the depiction of extraterrestrial life in movies. Director Ridley Scott brought visual style and atmosphere to particularly unglamorous and dismal setting. He also scared the hell out of audiences at the time with his slow burn story structure and editing style that hints, rather than shows. Overall, Alien is a text book example of how to make a horror movie and put a new spin on a classic and well-trodden concept.

Alien is a unique genre milestone. It challenged the established aesthetic created by 2001: A Space Odyssey of space travel being pristine, clinical and high tech and replaced it with a grimy, industrial quality. The space tug Nostromo is also a conspicuously “blue collar”, civilian venture, underwritten by a large corporation. As for H. R Giger’s xenomorph, it redefined the depiction of extraterrestrial life in movies. Director Ridley Scott brought visual style and atmosphere to particularly unglamorous and dismal setting. He also scared the hell out of audiences at the time with his slow burn story structure and editing style that hints, rather than shows. Overall, Alien is a text book example of how to make a horror movie and put a new spin on a classic and well-trodden concept.

Jerry Goldsmith’s sombre and portentous score is a key ingredient to the film’s brooding and claustrophobic atmosphere. Yet despite the quality of the music, Goldsmith felt that the effectiveness of his work was squandered by Ridley Scott and editor Terry Rawlings who re-edited his work and replaced entire tracks with alternative material. However what was left still did much to create a sense of romanticism and mystery in the opening scenes, then later evolving into eerie, dissonant passages when the alien starts killing the crew. The fully restored score has subsequently been released by specialist label Intrada and has a thorough breakdown of its complete and troubled history.

Perhaps the best track in the entire recording is the triumphant ending and credit sequence, which was sadly removed from the theatrical print of the film and replaced with Howard Hanson's Symphony No. 2 ("Romantic"). This cue reworks the motif from the earlier scene when the Nostromo undocks from the refining facility and lands on the barren planet, LV-426. It builds to a powerful ending which re-enforces Ripley’s surprise defeat of the xenomorph and its death in the shuttles fiery exhaust. Seldom has the horror genre been treated with such respect and given such a sophisticated and intelligent score. Despite its poor handling by the film’s producers, Alien remains one of Jerry Goldsmith’s finest soundtracks from the seventies and yet another example of his immense talent.

Classic Movie Themes: King Solomon's Mines

King Solomon’s Mines is a 1985 Cannon Films production based on the pulp works of H. Rider Haggard. It was quickly made to cash in on the ongoing success of Indiana Jones franchise, although the finished movie bears little resemblance to the classic original novel. Like most Cannon movies from that boom era, it was a cheap and fast enterprise that superficially sported a good cast, but ultimately didn’t do much with them. Veteran director J. Lee Thompson favoured a light and comic approach to the material, as the film’s budget could hardly sustain any major notable set pieces. Yet, it proved popular enough at the box office to warrant a sequel the following year. Allan Quatermain and the Lost City of Gold proved to be as equally silly but by then the public’s interest had waned.

King Solomon’s Mines is a 1985 Cannon Films production based on the pulp works of H. Rider Haggard. It was quickly made to cash in on the ongoing success of Indiana Jones franchise, although the finished movie bears little resemblance to the classic original novel. Like most Cannon movies from that boom era, it was a cheap and fast enterprise that superficially sported a good cast, but ultimately didn’t do much with them. Veteran director J. Lee Thompson favoured a light and comic approach to the material, as the film’s budget could hardly sustain any major notable set pieces. Yet, it proved popular enough at the box office to warrant a sequel the following year. Allan Quatermain and the Lost City of Gold proved to be as equally silly but by then the public’s interest had waned.

Set in 1910 in an unspecified part of colonial Africa, Allen Quartermain (Richard Chamberlin) is an adventurer and fortune hunter hired by Jesse Huston (Sharon Stone) to find her missing father. Professor Huston has been captured by a German military expedition led by Colonel Bockner (Herbert Lom) and Turkish slave-trader and adventurer, Dogati (John Rhys-Davies), who are searching for the legendary King Solomon’s Mines. Cliched adventures such as being chased by natives, wild animals and cooked in a pot ensue, along with modicum of cheap special effects. The screenplay is weak and tries to pass off a bunch of tired stereotypes as humour. Some viewers may find it a dumb, silly adventure. But for many it’s a tedious experience.

However, King Solomon’s Mines has one sole virtue in so far as it boasts a score by the legendary Jerry Goldsmith. Despite being intentionally composed in the idiom of John Williams Indiana Jones March, Goldsmith’s main title theme is sufficiently engaging in its own right. It exudes all of his usual sophistication and charm as well as being devilishly catchy. Despite being a musical caricature, the score, especially the title theme gets away with it in the same way as the The Rutles do. Once again it proves that Jerry Goldsmith could turn his hand to anything, musically speaking. Even when required to produce something “generic”, his work still remains a cut above the rest.

Classic Movie Themes: Basic Instinct

Paul Verhoeven has seldom made a movie without some semblance of controversy associated with it, and his 1992 neo-noir Basic Instinct was no different. Even before its US release, Basic Instinct courted controversy due over its overt sexuality and graphic depiction of violence. It was strongly opposed by gay rights activists, who criticised the film's depiction of homosexual relationships and the portrayal of a bisexual woman as a homocidal narcissistic psychopath. The opening murder with an icepick is still shocking twenty six years later and is an excellent showcase for makeup FX artists Rob Bottin.

Paul Verhoeven has seldom made a movie without some semblance of controversy associated with it, and his 1992 neo-noir Basic Instinct was no different. Even before its US release, Basic Instinct courted controversy due over its overt sexuality and graphic depiction of violence. It was strongly opposed by gay rights activists, who criticised the film's depiction of homosexual relationships and the portrayal of a bisexual woman as a homocidal narcissistic psychopath. The opening murder with an icepick is still shocking twenty six years later and is an excellent showcase for makeup FX artists Rob Bottin.

The plot is a text book example for the genre. Troubled police detective (Michael Douglas), returns from suspension to investigates a brutal murder, in which a manipulative and seductive woman (Sharon Stone) could be involved. Events quickly get out of hand as detective Nick Curran becomes personally involved in the case. The script by Joe Eszter has smoulders with sexual tension and is further punctuated by explosions of violence. Performances are universally good, elevating what is essentially a rather sleazy murder mystery into a far classier undertaking. The film also offers an interesting social commentary on contemporary US sexual politics. Let it suffice to say that beauty often harbours a dark heart.

Regardless of your views on the merit of the movie, Jerry Goldsmith score for Basic Instinct is absolute gem, finely balancing the suspense and the on-screen sexuality. He brilliantly blends mystifying strings, woodwinds, harp, along with piano to build a sense of tension. The soft, wistful title theme is both alluring as well as ominous; a subtle warning of the events that follow in the movies opening scene. The strings section carries the burden of the work, as they do for every other cue throughout the remainder of the score. Basic Instinct remains a text book example of the craft of the late Jerry Goldsmith, bringing distinct elements of class and maturity to the raw passion of the movie.

The Rambo Phenomenon (1982 - 2008)

The cinematic character of John J Rambo is heavily associated with the politics of the eighties and the ascending right-wing attitudes of the era. His name has entered the popular sub culture and means different things to different people. His name is used as a pejorative term by certain political lobbies, who see him as stereotypical incarnation of blind patriotism and “might is right” minsdet. It is a name also sadly linked to the Hungerford Massacre in the UK by Michael Ryan in 1987. It was alleged, particularly by tabloid newspapers, that Ryan was inspired by the film Rambo: First Blood Part II, with some claiming he wore armed-forces style clothing. Rambo was cited as an example of a negative media influence, which was particularly relevant in the wake of the controversy over video nasties in the UK at that time. It is now claimed that Ryan had never seen the film, but the allegations provided sensationalist headlines and imagery and so the label stuck.

The cinematic character of John J Rambo is heavily associated with the politics of the eighties and the ascending right-wing attitudes of the era. His name has entered the popular sub culture and means different things to different people. His name is used as a pejorative term by certain political lobbies, who see him as stereotypical incarnation of blind patriotism and “might is right” minsdet. It is a name also sadly linked to the Hungerford Massacre in the UK by Michael Ryan in 1987. It was alleged, particularly by tabloid newspapers, that Ryan was inspired by the film Rambo: First Blood Part II, with some claiming he wore armed-forces style clothing. Rambo was cited as an example of a negative media influence, which was particularly relevant in the wake of the controversy over video nasties in the UK at that time. It is now claimed that Ryan had never seen the film, but the allegations provided sensationalist headlines and imagery and so the label stuck.

US President Ronald Reagan made reference to the character on several occasions during his two terms in office. Upon the release of 39 American hostages in June 1985 said, “after seeing Rambo last night, I know what to do next time this happens”. Hardly diplomatic words. Several months later, pleading for tax reform, Reagan said, “Let me tell you, in the spirit of Rambo, we're going to win this thing”. These extraordinary references by an American president attest to the power and ubiquity of the Rambo phenomenon. That fact that a contrived cinematic character could become a powerful political metaphor is still intriguing. Even today Rambo remains a name that gets a reaction and invokes an emotional response. However, often people’s perceptions are erroneous, based around popular headlines rather than an awareness of the central character himself. If we look at the history of the character, it is not as black and white as it first appears.

The first film featuring John Rambo was First Blood, released in 1982 and directed by Ted Kotcheff. It took David Morrell's traumatised twenty-year-old character and turned him into a 36, melancholic and philosophical veteran. The film also made some subtle plot alterations to negate any moral ambiguity that featured in the novel. Stallone is put upon and although violently breaks out of the Police station, does not kill first. Where as in the book, Rambo, instinctively reacts to provocation due to his military training and guts one of the police officers. Kotcheff's tried to tackle the wider issue of how a nation treats it war veterans, especially in light of a military defeat, whereas the book focused on a generation of youth that had been rendered dysfunctional and homicidal due to their training and experience. It is a surprisingly thoughtful film and very much a horse of a different colour, compared to what followed.

Rambo: First Blood Part II was released in 1985 and rather than reflecting on America's historical wounds, offered a populist fantasy in which John Rambo got to re-write history and rescue a group of POWs from Vietnam. It was a massive commercial success and succinctly reflected the social and political mood of the US at the times. There is absolutely no attempt to objectively look at the complex issues that lead to the failure of the Vietnam war. We are instead presented with arbitrary bad guy stereotypes, whose evil status is denoted by their penchant for looking through binoculars fiendishly and speaking in hackneyed foreign accents. School boy politics aside, the film was a solid action vehicle for Stallone and sealed his action star status. It was competently directed by George P. Cosmatos and superbly shot by legendary cinematographer Jack Cardiff. The body count is ludicrously high and Rambo special forces skills go from the credible to the incredible.

By 1988 the world was changing rapidly. The Cold War was slowly coming to an end as Russia entered a new period of Gasnost and Perestroika. Due to production delays, the plot of Rambo III centring around rescuing Colonel Trautman from Afghanistan, seemed somewhat out of step with current affairs. However, the basic premise of the bond of friendship between student and master was sound and the film directed by veteran second unit director Peter MacDonald, supplied copious amount of action. However, due to the backlash in the UK against the franchise by the tabloid press, allegedly over the Hungerford massacre, the film was heavily censored. This arbitrary knee jerk reaction achieved nothing tangible and in subsequent years, all cuts have been waived by the BBFC. This entry is perhaps the most underrated in the series and curiously enough adds a slightly more flippant and humorous facet to Rambo's character.

In Rambo, the fourth instalment of the franchise, directed in 2008 by Stallone himself, finds our protagonist rescuing a group of Christian missionaries, from the Burmese military. Unlike the previous two sequels, there is far less of a political dimension to the story. The Burmese army are simply a catalyst for the action and are not explored in any depth. This time Rambo presents us with the age-old dilemma about the use of violence against violence. The Burmese Army brutally shoot, blow up, bayonet, burn, mutilate, and rape the innocent villagers. Yet exactly the same retribution is visited upon them. One of the Christians muses that it is never justifiable to use violence or to kill. Ironically (or predictably) he beats a soldier to death with a stone at the films climax. Is this an effective illustration of the inevitability of violence? Other films have argued otherwise. Ghandi depicts the destiny of a nation, changed through nonviolent protest. However, he was not faced with the prospect of genocide.

Film critic Mark Kermode slated Rambo as totally morally bankrupt, a claim also made against the 1985 instalment. Stallone counters this argument by stating that violence is simply human nature. It is what we are. A point that is often unpalatable to some intellectual quarters, possibly because it is so near to the truth. The writer Robert A. Heinlein proposed that violence has settled more issues in history than has any other factor and that all actions in human society are governed by force. The very act of voting is a manifestation of exerting one’s dominance. Also, there is the debate that violence can be justified if the cause is morally valid. It is intriguing that the Christians depicted in the 2008 film Rambo, are at odds with their faiths historical legacy on this very issue.

Debating the wider moral and philosophical aspects of this franchise is not as easy a question as one would expect. Is the entire Rambo phenomenon broad escapist entertainment or a politically incorrect cinematic slaughter house? Is it a revisionist western or nihilistic sanguinary pornography? Despite initial statements that a fifth film may manifest itself, Stallone appears to have put that idea to bed. It would seem that the final images of part four, with John Rambo returning to his family home is indeed to be the definitive ending. For good or ill, Rambo has become an integral part of 20th century pop culture and the name has assumed a wider meaning and become part of the contemporary lexicon. Some argue that cinema does not set the cultural agenda but merely reflects it. If that is so, then don’t shoot the messenger, especially when he's an ex Green Beret.

Finally, it would be impossible to write about the Rambo series without mentioning the work of composer Jerry Goldsmith. He provided the score for the first three films and after his death, Brian Tyler continued with his main themes for the fourth movie. Goldsmith's music for the franchise is very accomplished and adds an additional layer to the central character. His various cues especially for the action sequences demonstrates how a musical score can enhance a film. Posted below is the main theme for the first film, which is has become synonymous with the Rambo character and encapsulates the late composer’s immense talent.