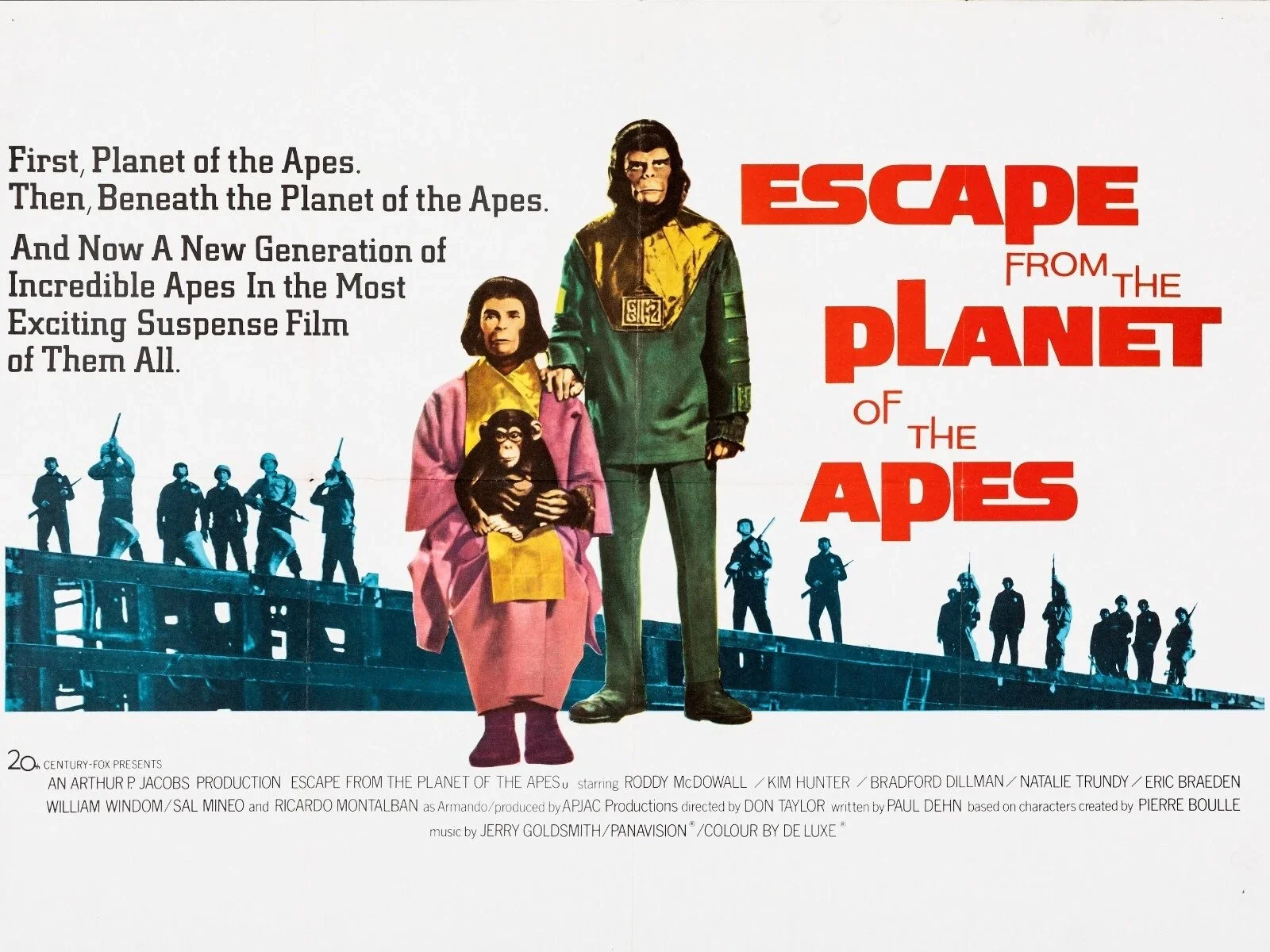

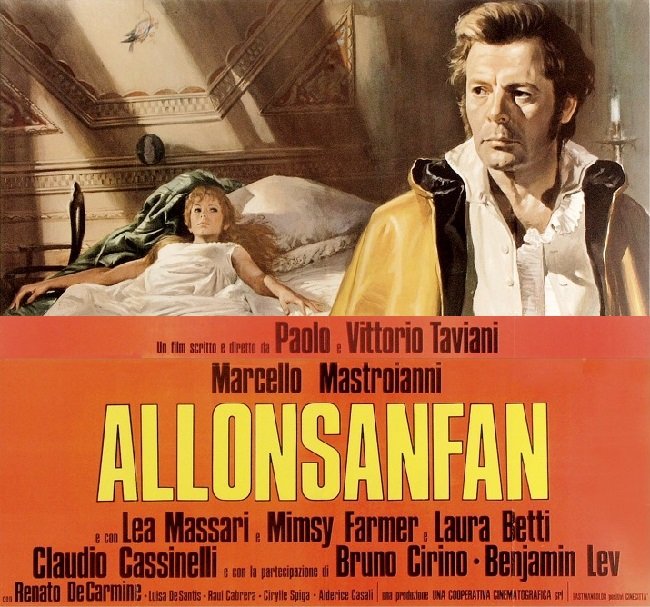

Classic Movie Themes: Allonsanfàn

Allonsanfàn (1974) is an Italian historical drama film written and directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani. The title of the film derives from the first words of the French Revolutionary anthem La Marseillaise (Allons enfants, IE “Arise, children”). It is also the name of a character in the story. Set against the backdrop of the Italian Unification in early 19th-century Italy, Marcello Mastroianni stars as an ageing revolutionary, Fulvio Imbriani, who becomes disillusioned after the Restoration and endeavours to betray his companions, who are organising an insurrection in Southern Italy. Allonsanfàn is a complex film that is not immediately accessible to those unfamiliar with the intricacies of Italian political history nor the arthouse style of the Taviani brothers. However, it is visually arresting and features a rousing score by Ennio Morricone.

Allonsanfàn (1974) is an Italian historical drama film written and directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani. The title of the film derives from the first words of the French Revolutionary anthem La Marseillaise (Allons enfants, IE “Arise, children”). It is also the name of a character in the story. Set against the backdrop of the Italian Unification in early 19th-century Italy, Marcello Mastroianni stars as an ageing revolutionary, Fulvio Imbriani, who becomes disillusioned after the Restoration and endeavours to betray his companions, who are organising an insurrection in Southern Italy. Allonsanfàn is a complex film that is not immediately accessible to those unfamiliar with the intricacies of Italian political history nor the arthouse style of the Taviani brothers. However, it is visually arresting and features a rousing score by Ennio Morricone.

The Tavianis brothers’ previous composer Giovanni Fusco introduced Morricone to the directors, who initially didn't want to use any original music for the film. As Morricone was not disposed towards arranging anyone else's work he insisted upon writing his own material or he would leave the production. Upon hearing the motif he created for the climatic “dance” scene, the Tavianis brothers immediately set aside their previous objections and gave Morricone free reign. Hence, Morricone’s deliciously inventive score is part of the fabric of the film, providing a pulse to the story. This is most noticeable in the scene in which Fulvio’s sister Esther (Laura Betti) turns a half-remembered revolutionary song into a full-blown song-and-dance number and when Fulvio himself borrows a violin in a restaurant to impress his son. Allonsanfàn may not be to everyone’s taste but Morricone’s score is very accessible.

Perhaps the most standout track from the film’s score is “Rabbia e tarantella” (Revolution and Tarantella). A Tarantella is a form of Italian folk dance characterised by a fast upbeat tempo. Morricone has crafted a remarkably rhythmic piece featuring aggressive piano and low-end brass against a backdrop of a stabbing string melody. All of which is driven and underpinned by the timpani drum which robustly punctuates the track. It is certainly not your typical tarantellas of Italian folk but it is a catchy piece that highlights the innate understanding of music that Ennio Morricone possessed and how he could bring this talent to bear on any cinematic scene. “Rabbia e tarantella” was subsequently used during the closing credits of Quentin Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds (2009). Due to its inherent quality it survives being transplanted into a film with a completely different context.

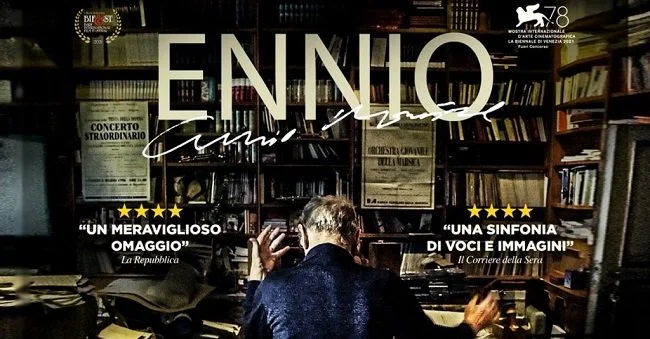

Ennio (2021)

Giuseppe Tornatore’s sprawling documentary Ennio, is a finely detailed and absorbing exploration of prolific and iconic Italian composer Ennio Morricone. Despite its very traditional approach to its subject matter, looking at Morricone’s career chronologically, intercut with celebrity talking heads, it still manages to convey the unorthodox, innovative and experimental nature of the composer. The 156 minute running time is not necessarily the impediment that one expects. Rather it is the sheer weight of the emotional impact that comes from Morricone’s music that is at times overwhelming. Archival footage and a new and comprehensive interview recorded just prior to the composer’s death in 2020 is intercut with a wealth of audio cues and concert footage from a broad cross section of his work. The result is most illuminating with regard to the man and his approach to composing. The conclusion backed by many of those interviewed is that Ennio Morricone has shaped the nature of film music and elevated it to an artform.

Giuseppe Tornatore’s sprawling documentary Ennio, is a finely detailed and absorbing exploration of prolific and iconic Italian composer Ennio Morricone. Despite its very traditional approach to its subject matter, looking at Morricone’s career chronologically, intercut with celebrity talking heads, it still manages to convey the unorthodox, innovative and experimental nature of the composer. The 156 minute running time is not necessarily the impediment that one expects. Rather it is the sheer weight of the emotional impact that comes from Morricone’s music that is at times overwhelming. Archival footage and a new and comprehensive interview recorded just prior to the composer’s death in 2020 is intercut with a wealth of audio cues and concert footage from a broad cross section of his work. The result is most illuminating with regard to the man and his approach to composing. The conclusion backed by many of those interviewed is that Ennio Morricone has shaped the nature of film music and elevated it to an artform.

Morricone’s personal recollections of his youth and of his family’s poverty are candid. His Father, a trumpet player of some note, insisted his son learn music as a means to “put food on the table”. Morricone’s skill took him to the Saint Cecilia Conservatory to take trumpet lessons under the guidance of Umberto Semproni. He then went on to study composition, and choral music under the direction of Goffredo Petrassi. However, despite this very formal music education, Morricone took an innovative approach to his arrangements and would often use unorthodox sounds to add character to his work. During his tenure at RCA Victor as senior studio arranger, his contemporary approach found him working with such artists as Renato Rascel, Rita Pavone and Mario Lanza. As his reputation subsequently grew, composing for film became a logical and practical career progression. However, this was something that was looked down on by his more formal colleagues. A view that changed overtime as the calibre of his work became undeniable.

Ennio features a wealth of soundbites from prior interviews and new ones, from old friends, fellow musicians and admirers. Some are profound, some gush and others are curious by sheer dint of their inclusion. The views of Bruce Springsteen are somewhat hyperbolic and Paul Simonon makes a single obvious statement. However the insight we gain from classical composer Boris Porena is extremely thoughtful and interesting. As are the views of Hans Zimmer and Mychael Danna. There are also numerous personal anecdotes from assorted collaborators, including Joan Baez, Paolo and Vittorio Taviani as well as Roland Joffé. Baez recalls how Morricone intuitively wrote for her entire vocal range. The Taviani brothers reflected upon how they were at odds with the maestro only to be totally won over by work. Joffé reflects how Morricone wept when he saw The Mission, stating it didn’t need a score. Often it is Morricone’s own recollections that are the most intriguing. For someone of such exceptional talent he remains grounded, sincere and protective of his craft.

Director Giuseppe Tornatore naturally focuses on his own collaborations with Morricone, especially Cinema Paradiso, but overall Ennio is about the man, his philosophy and his joy of music. Some critics have inferred that this documentary is too Italian-centric but that is a crass complaint. Sixty years of Italian culture, both artistically and politically, are reflected in Morricone’s work. Hence there is significance in the reminiscences of Italian pop stars contracted to RCA who owe their success to Morricone’s innovative arrangements and production values. Ennio also features several anecdotes that are surprising and revealing, such as how the maestro missed an opportunity to write the soundtrack for Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Long and at times a little overwhelming, Ennio is a fitting tribute to the great composer. It is also a testament to the skills of editor Massimo Quaglia for cogently assembling such a vast amount of information and sentiment into a coherent narrative.

Ennio Morricone (1928 - 2020)

Treasure of the Four Crowns (1983) is a somewhat confused and shoddy action movie that attempts to ride on the coattails of both Raiders of the Lost Ark and the 3-D revival of the time. It lurches between set pieces where anything and everything is thrown at the camera, to moments of unpleasantness and then into slapstick comedy. Yet there is one aspect of this unremarkable film that remains with the viewer after they’ve endured its 97 minute running time. The opulent and charismatic orchestral score by Ennio Morricone. Because "Maestro" Morricone always brought his immense talent to bear on a film regardless of its quality or provenance. Hence there are just as many genre movies and exploitation films with exceptional Morricone soundtracks as there are cinematic masterpieces and art house classics. As writer and director Edgar Wright said “he could make an average movie into a must see, a good movie into art, and a great movie into legend”.

Treasure of the Four Crowns (1983) is a somewhat confused and shoddy action movie that attempts to ride on the coattails of both Raiders of the Lost Ark and the 3-D revival of the time. It lurches between set pieces where anything and everything is thrown at the camera, to moments of unpleasantness and then into slapstick comedy. Yet there is one aspect of this unremarkable film that remains with the viewer after they’ve endured its 97 minute running time. The opulent and charismatic orchestral score by Ennio Morricone. Because "Maestro" Morricone always brought his immense talent to bear on a film regardless of its quality or provenance. Hence there are just as many genre movies and exploitation films with exceptional Morricone soundtracks as there are cinematic masterpieces and art house classics. As writer and director Edgar Wright said “he could make an average movie into a must see, a good movie into art, and a great movie into legend”.

Ennio Morricone was a prodigious composer, who eschewed Hollywood despite his success. He preferred to compose at his palazzo in Rome, working at a desk as opposed to a piano. He wrote in pencil on score paper, creating all orchestra parts from what he could hear in his mind. He would frequently compose after reading a just a script, viewing rushes or a rough cut of a film. Due to his musical diversity and at times experimental approach, he was much sought after by similarly creative film makers. His musical range was exceptional featuring an array of techniques; tarantellas, psychedelic vocalisations, sumptuous love themes along with minimalist beats to underscore tension. He was not afraid to be quirky or to use that most dangerous musical device silence. He composed for TV, cinema, wrote concert pieces, and orchestrated music for singers including Joan Baez, Paul Anka and Anna Maria Quaini, the Italian pop star known as Mina. Whatever he did both he and his music always left an impression.

Given his extensive body of work across multiple genres, it is difficult to collate a short list of material that adequately summarises Ennio Morricone’s musical capabilities. His mainstream renown stems from his work with director Sergio Leone and “The Dollar” trilogy which has quite rightly become an integral part of cinematic pop culture. However his collaborations with the “Master of the Giallo”, Dario Argento, are equally noteworthy. The Bird With The Crystal Plumage (1970) features pop inflected vocal harmonies, avant improvisation and salacious lounge music. The Mission (1986), features a plot device in which a Jesuit Priest uses his Oboe to fill the cultural divide between the Catholic Church and the idigenous people of Paraguay. This is sublimely realised by Morricone in his iconic piece “Gabriel’s Oboe”. Director John Carpenter 1982 sci-fi horror The Thing benefits greatly from Morricone’s minimalist synth driven score. And the sleazy 1972 thriller What Have You Done to Solange? becomes more than the sum of its parts due to melancholic and melodic Morricone score.

Here is a short and personal selection of music cues and tracks by Ennio Morricone that I enjoy. He leaves behind an exemplary legacy and body of work as well as having influenced several generations of musicians and composers. A friend of mine who is also a “man of the cloth” and a commensurate fan, once told me that he feels that “there are brief glimpses of the divine” in Morricone’s work and that on occasions “it reflects the majesty of creation”. Although I’m not especially religious myself, I feel that there is truth in these words. Ennio Morricone’s music, especially his more sumptuous scores for the likes of Roland Joffé, Giuseppe Tornatore and Brian De Palma, contain an inherent beauty. And that beauty is pure and timeless. Addio Maestro.