World War Z: The Complete Edition by Max Brooks (2013)

The zombie genre is a narrative seam that has been heavily mined in recent years. There seems to have been a never-ending supply of films, television shows and video games involving the undead over the last two decades. Which is why the notion of society being destroyed by its own citizens has somewhat lost its intellectual and horrific lustre. Hence I can understand people rolling their eyes at the mention of the novel World War Z by Max Brooks. The 2013 film adaptation starring Brad Pitt, which jettisoned most of the source text's innovations, isn’t the best advertisement for the book’s virtues. However, if you take the time to look beyond the hyperbolic title, you’ll find World War Z a work of singular intelligence which uses the zombie genre as a means to explore multiple socio-economic and political themes.

The zombie genre is a narrative seam that has been heavily mined in recent years. There seems to have been a never-ending supply of films, television shows and video games involving the undead over the last two decades. Which is why the notion of society being destroyed by its own citizens has somewhat lost its intellectual and horrific lustre. Hence I can understand people rolling their eyes at the mention of the novel World War Z by Max Brooks. The 2013 film adaptation starring Brad Pitt, which jettisoned most of the source text's innovations, isn’t the best advertisement for the book’s virtues. However, if you take the time to look beyond the hyperbolic title, you’ll find World War Z a work of singular intelligence which uses the zombie genre as a means to explore multiple socio-economic and political themes.

Instead of a traditional novel with several central characters and a linear story arc, World War Z is a collection of fictional interviews that take place between survivors of the zombie apocalypse from around the world and a fictional version of the author Max Brooks. Each personal vignette provides a first hand account of a specific event within the history of the zombie apocalypse and its subsequent consequences upon the narrator or the wider world. These personal anecdotes often obliquely reference wider happenings such as a specific government policy, military engagement or a mass migration. They frequently allude to things that the reader doesn’t directly know about. However, there is always sufficient information to deduce what is being inferred, be it wide scale cannibalism, emergency legislation to deal with civil unrest, or the collapse of specific public institutions.

Hence we hear from Fernando Oliveira, a Brazilian former surgeon, who recollects how the zombie virus was initially spread via the illegal organ trade that he was part of. Then there is Jurgen Warmbrunn, a Mossad agent, who co-write the first formal document recommending countermeasures against the undead. He reflects on how it was distributed to all major governments around the world, who subsequently dismissed it. There are also interviews with everyday people, such as Jesika Hendricks, an American-Canadian woman. She recounts how she survived the first winter after the Great Panic when she and her parents fled north, hoping the cold would freeze the zombies. These interviews personalise the global disaster, while simultaneously exploring the failings of government and how capitalism is ill equipped to deal with catastrophic events.

There is a lot of interesting analysis of both contemporary society and politics within World War Z. Both the public and the incumbent US government, initially refuse to countenance what is exactly going on, leading to a period of history referred to as the Great Denial. The pharmaceutical industry quickly exploits the situation by producing a placebo drug, which the government happily greenlights to buy time. When the modern US military finally faces a massed attack of undead outside Yonkers, their tactics and weapons fail. The shock and awe they depend on to psychologically crush their opponents, is absent in an enemy that is oblivious to their technological superiority. Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the story is the US government's attempts to repurpose the surviving workforce, with 65% having no viable skills, apart from manual labour, in a post apocalyptic world.

The audiobook version of World War Z has a somewhat complicated history. Random House published an abridged version running 5 hours and 59 minutes in 2007. The book is read by Brooks (who previously had a career in voice acting) and includes Carl Reiner, Mark Hamill and Henry Rollins portraying some of the characters interviewed. Later in 2013, Random House released a revised 12 hours and 9 minutes audiobook titled World War Z: The Complete Edition (Movie Tie-in Edition): An Oral History of the Zombie War. It contains the entirety of the original, abridged audiobook, as well as new recordings of the previous absent material by such actors as Simon Pegg, Jeri Ryan and Parminder Nagra. There is also an alternative version available on Audible UK, with a completely different voice cast.

For the purpose of this review I listened to the rather ponderously named World War Z: The Complete Edition (Movie Tie-in Edition): An Oral History of the Zombie War. Although a lengthy production, the interview format easily allowed me to listen in stages over the course of the week. Sometimes an all star cast can be an impediment to an audiobook adaptation, with individual voice actors becoming the focus of attention instead of the prose. However, in this instance the robust cast imbues the interviews with a sense of credibility, making the various recollections very personal and human. There are no accompanying audio effects and the adaptation lacks a musical score. A simple ominous sting separates each personal recollection. This minimalist approach works very well, as it would have been a mistake to over embellish the production.

Nineteen years on from its publication, World War Z remains relevant, thought provoking and even a little portentous. The COVID-19 pandemic, although far from a zombie apocalypse, certainly shared some parallels with the themes of the book. There was government denial, flagrant business profiteering and a public that was unprepared for such a radical change to their daily existence. The current decline in democratic processes and politics in western civilisation has created an atmosphere of impending societal collapse. Is the broken world that is so vividly depicted within the pages of World War Z an indication of our own future? Max Brooks wrote metaphorically of zombies undoing our civilisation. We currently seem to be doing something similar but without the metaphor.

Unnatural Causes by Dr Richard Shepherd (2018)

Dr Richard Shepherd is a senior forensic pathologist with over 30 years’ experience, consisting of 23,000 postmortems. His book, Unnatural Causes, explores his career and his devotion to the truth in determining how each of his cases died. Over the course of his career this includes victims of mass disasters, homicides, and those who have died in their own homes from unknown causes. Dr Shepherd’s job is to ascertain a cause of death based upon the facts and data presented. Each case is described with detail and empathy and it’s surprising how much the reader becomes immersed in the methodical approach that each postmortem entails. Furthermore, it is very satisfying to learn of Dr Shepherd’s verdict. However, far from being a technical dissertation on a succession of cases, this is a deeply personal and humane book which addresses the impact of the author’s career upon himself and his family. It is written with a surprising degree of literary flair and is profoundly thought provoking and moving.

Dr Richard Shepherd is a senior forensic pathologist with over 30 years’ experience, consisting of 23,000 postmortems. His book, Unnatural Causes, explores his career and his devotion to the truth in determining how each of his cases died. Over the course of his career this includes victims of mass disasters, homicides, and those who have died in their own homes from unknown causes. Dr Shepherd’s job is to ascertain a cause of death based upon the facts and data presented. Each case is described with detail and empathy and it’s surprising how much the reader becomes immersed in the methodical approach that each postmortem entails. Furthermore, it is very satisfying to learn of Dr Shepherd’s verdict. However, far from being a technical dissertation on a succession of cases, this is a deeply personal and humane book which addresses the impact of the author’s career upon himself and his family. It is written with a surprising degree of literary flair and is profoundly thought provoking and moving.

There are many standout cases and medical anecdotes throughout Unnatural Causes. Too many to choose from. However, one that proved to be particularly poignant is a case regarding an old lady who lived alone. She was found dead by her cleaner, naked under her kitchen table with the room in a state of disarray. Neighbours implied she may have been going senile and the police suspected a burglary due to the way the furniture and kitchen drawers have been disturbed. The medical conclusion was quite contradictory. The victim had in fact died of hyperthermia. Survivors of this condition have described feeling very hot as their temperature dropped and thought that removing their clothes was an appropriate response. Furthermore, victims of hypothermia will often seek to die in an enclosed space as they lose their cognitive ability. “Hide-and-die” syndrome as it has been named. What made this case especially sad was that it was the first in which Dr Shepherd noticed that there was no family to mourn the bereaved.

As well as exploring interesting medical phenomena and procedures Unnatural Causes is also a rather succinct history of many of the major tragedies that have occurred in the UK between the 1980 and 2015. From the Hungerford massacre and the King’s Cross fire of 1987 to the Clapham Junction rail crash in 1988 and the Marchioness disaster of 1989. Dr Shepherd taps into the mood and shock that each event brought the nation and touches upon the ramifications, such as the creation of modern “health and safety” culture that many of us now just take for granted and complain about. His observations about corporate and state attitudes to risk and the lack of accountability are still very pertinent. His thoughts and reflections upon several high-profile cases are also thought provoking. Such as the carrying out of Stephen Lawrence’s postmortem and that of Princess Diana and Dr Harold Shipman. The political and social fall out of all three cases are still being felt today.

In addition to the wealth of medical analysis and exploration of the duty of care that a forensic pathologist has, Dr Shepherd does not avoid addressing the realities of his work upon himself and the personal cost to his mental health and his immediate family that his career has caused. The very nature of a forensic pathologist means that your work hours are irregular, and this alone will put an immense strain upon any relationship. Then there is the emotional compartmentalisation and the requirement to maintain a professional detachment in one’s work. This is a reflective and poignant memoir and a meditation on the duality of both life and death. It is also an attempt to reconcile the scientific necessity to determine a cause of death with the common misconception that a postmortem is an act of violation. Something that many bereaved families feel at times. Dr Shepherd addresses this wisely and with great sympathy but clearly states that it is an act of great compassion. Determining a cause of death is a sign of a caring society. Unnatural Causes is a moving, informative, and genuinely humane book that will fascinate both medical professionals and casual readers alike.

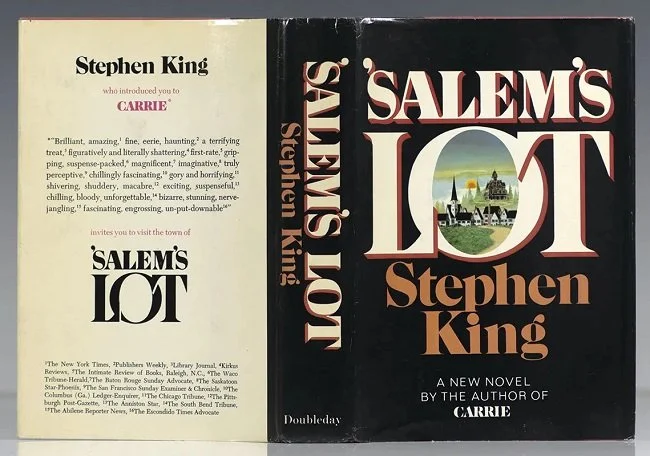

Salem's Lot by Stephen King (1975)

When a book is as well known, well loved and as critically revered as Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot, it seems somewhat redundant to write yet another review of it. I doubt I can add anything significant or original to say about its virtues and merits. So I won’t attempt to do so. I’ll simply share some thoughts on the book in question and leave it at that. Firstly, I read the novel in 1981 when it was more than half a decade old. I had already seen the 1979 television mini-series, directed by Tobe Hooper, which I had enjoyed immensely. Luckily, I had an exceptionally good English teacher at school at the time, who impressed upon me the challenges involved in adapting books for TV or film. Hence, when I actually sat down to read Salem’s Lot I expected it to be distinctly different to what I had seen already. And it was. An utterly enthralling story, that absorbed me totally and scared me shitless. It left a profound mark upon me. Last month, approximately 41 years later, I read it again and enjoyed it even more.

When a book is as well known, well loved and as critically revered as Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot, it seems somewhat redundant to write yet another review of it. I doubt I can add anything significant or original to say about its virtues and merits. So I won’t attempt to do so. I’ll simply share some thoughts on the book in question and leave it at that. Firstly, I read the novel in 1981 when it was more than half a decade old. I had already seen the 1979 television mini-series, directed by Tobe Hooper, which I had enjoyed immensely. Luckily, I had an exceptionally good English teacher at school at the time, who impressed upon me the challenges involved in adapting books for TV or film. Hence, when I actually sat down to read Salem’s Lot I expected it to be distinctly different to what I had seen already. And it was. An utterly enthralling story, that absorbed me totally and scared me shitless. It left a profound mark upon me. Last month, approximately 41 years later, I read it again and enjoyed it even more.

Salem’s lot contains a lot of the hallmarks of why people love King’s writing. He has an uncanny ability to depict everyday people with their flaws, quirks and vices. He will often devote a lot of time exploring the thoughts and feelings of characters, which often are not entirely necessary to expedite the plot but it just adds to credibility of the world he has created. In the case of Salem’s Lot, the town is ultimately defined by its people and not just the detailed description of the buildings and local geography. Hence King devotes a lot of time to interesting vignettes about Dud Rogers who runs the town dump, telephone repairman Corey Bryant and the graveyard digger, Mike Ryerson. The novel is at its best when getting to know the townsfolk, especially as things gradually take a turn for the worse. I appreciated this aspect of the book so much more the second time round, whereas my younger self craved the horror and panic of the book’s latter stages.

When the vampire infection begins to spread, King manages to generate a palpable sense of creeping dread. The vampires are not just a clumsy plot device but are wily and sophisticated foes. This is made worse by the close knit nature of the community and the fact that people are being hunted by those they know. The story fosters a keen sense of hopelessness, as it becomes clear that the remote and insular nature of Salem’s Lot is working against the interests of our protagonists, author Ben Mears, college graduate Susan Norton, school teacher Matt Burke, doctor Jimmy Cody, local boy Mark Petrie and local priest Father Callahan. The story reaches its peak when the vampire threat feels overwhelming both physically and spiritually. The ending is far from black and white and although it addresses and resolves some issues, it does not neatly conclude all the story lines. It implies a successful conclusion to a battle but not necessarily a definitive victory.

Salem’s Lot is a great example of vintage Stephen King, succinctly highlighting why he was a rising star at the time. The novel is a microcosm of the time it was written, capturing the neurosis and world weariness of the US public in the years after Watergate and the Vietnam war. It is about disillusionment and a fear of the future. A concern that forces are abroad that are unchecked and uncontrollable. It is also a metaphor for the continuous battle of wills between rural and urban America. Even the parochial town of Salem’s Lot is a bastion of modernity compared to the ancient and sinister powers of Kurt Barlow. But perhaps the jewel in the crown of this novel is King’s ability to capture the realities and cultural distinction of living in a small town. Salem’s Lot remains a milestone in horror writing and in American literature per se. It is a book I would recommend not only to horror enthusiasts but to anyone who enjoys well crafted characters. If you are a student of writing then Salem’s Lot has a lot to teach.

The Case of Charles Dexter Ward by H. P. Lovecraft - Read by Neil Hellegers

Charles Dexter Ward is a young man from a prominent Rhode Island family with a keen interest in history. He spends much of his childhood wandering the streets of ancient Providence, drawn inexorably to its architecture, as well as it’s colourful heritage. As an adult he continues his antiquarian leanings and subsequently discovers a hitherto unknown ancestor, Joseph Curwen. One with a shadowy past which hints at the pursuit of alchemy and other arcane practises. Charles decides to uncover the truth regarding Joseph Curwen and over time his interest changes into obsession. His Father begins to worry about his son’s fixation and the family Doctor, Marinus Bicknell Willett, decides to keep an eye upon the youth’s state of mind. A series of curious events hint at a growing eldritch malevolence and Doctor Willett begins to suspect that Charles is in grave danger from a menace stretching across time.

Charles Dexter Ward is a young man from a prominent Rhode Island family with a keen interest in history. He spends much of his childhood wandering the streets of ancient Providence, drawn inexorably to its architecture, as well as it’s colourful heritage. As an adult he continues his antiquarian leanings and subsequently discovers a hitherto unknown ancestor, Joseph Curwen. One with a shadowy past which hints at the pursuit of alchemy and other arcane practises. Charles decides to uncover the truth regarding Joseph Curwen and over time his interest changes into obsession. His Father begins to worry about his son’s fixation and the family Doctor, Marinus Bicknell Willett, decides to keep an eye upon the youth’s state of mind. A series of curious events hint at a growing eldritch malevolence and Doctor Willett begins to suspect that Charles is in grave danger from a menace stretching across time.

The Case of Charles Dexter Ward by H. P. Lovecraft, is a short novel that first appeared in Weird Tales in 1941. It is an uncomplicated story with a straightforward narrative arc. A young man’s obsession with an unsavoury ancestor leads to him replicating his alchemical and cabalistic research with suitably unpleasant results. However, it’s strength lies in the details that Lovecraft lavishes upon the proceedings. The loquacious descriptions of Providence, the historical details of 18th century life and culture in the State of Rhode Island and the inclusion of real characters from the era, such as Abraham Whipple, John and Moses Brown and Esek Hopkins is compelling. Once again Lovecraft alludes to ancient and arcane forces lurking beyond the veil of human understanding and perception. As ever the terror he evokes lies in the suggestion of something unfathomably evil and utterly alien impinging upon our world.

This unabridged reading of The Case of Charles Dexter Ward by Neil Hellegers is well paced and atmospheric. Hellegers, who has a great deal of experience with recording audio books, has clear diction and measured intonation, providing subtle detail to each character. His pronunciation of some of the complex names in the Cthulhu Mythos is assured. The story’s six hour running time is broken down into manageable audio chapters. Overall this is a well presented and exclusive reading of Lovecraft’s story, to be found only on Audible. It is accessible to both those familiar with the writings of H. P. Lovecraft and those who are new to his body or work. It certainly features one of his most notable and sinister villains. The story leaves several plot devices purposely vague and it is enjoyable to ponder on them after listening.

At the Mountains of Madness by H.P. Lovecraft - Read by Richard Coyle

At the Mountains of Madness is a story told from a first-person perspective by geologist William Dyer, a professor from Miskatonic University in Arkham, a fictional town in Essex County, Massachusetts USA. When a new scientific expedition to Antarctica is announced, Dyer breaks his silence and discloses hitherto unknown and closely kept secrets about his own explorations of the continent and exactly what befell his own expedition. He details how his team found the preserved remains of 14 prehistoric life forms unknown to science and outside of the existing geological and evolutionary timescale. He goes on to recount how some of the men and sled dogs are killed under mysterious circumstances. Dyer and graduate student Danforth, subsequently explored a mountain range by plane and discovered a vast, abandoned stone city, which is alien to any form of human architecture. What is the secret of this ancient ruin? Can Dyer convince subsequent explorers to stay clear of “the mountains of madness”.

At the Mountains of Madness is a story told from a first-person perspective by geologist William Dyer, a professor from Miskatonic University in Arkham, a fictional town in Essex County, Massachusetts USA. When a new scientific expedition to Antarctica is announced, Dyer breaks his silence and discloses hitherto unknown and closely kept secrets about his own explorations of the continent and exactly what befell his own expedition. He details how his team found the preserved remains of 14 prehistoric life forms unknown to science and outside of the existing geological and evolutionary timescale. He goes on to recount how some of the men and sled dogs are killed under mysterious circumstances. Dyer and graduate student Danforth, subsequently explored a mountain range by plane and discovered a vast, abandoned stone city, which is alien to any form of human architecture. What is the secret of this ancient ruin? Can Dyer convince subsequent explorers to stay clear of “the mountains of madness”.

At the Mountains of Madness was written by H.P. Lovecraft in 1931. The novella was originally serialised in Astounding Stories magazine in the US. While considered by fans to be an integral part of the Cthulhu Mythos some critics have argued that the author was attempting to “demythologise” his earlier work. I do not hold with this school of thought but I do consider the novella to be one of the author’s best works. It has a cosmic scope of vision and its sinister tone hints at so much more than the immediate horror. At the Mountains of Madness has proven so popular there have been several aborted attempts to bring it to the silver screen, with names such as Steven Spielberg and Guillermo Del Toro associated with the production. In the meantime the 2010 adaptation by Ladbroke Radio productions for BBC Radio 4 Extra, offers a superb five part dramatisation.

Read by actor Richard Coyle and accompanied with ambient music and sound effects, this concise audio version of the novella is a brooding and atmospheric affair. Purists should note that this is an abridged adaptation but the story does not suffer in any way by having some of the descriptive fat paired away. As for Richard Coyle his narration is authoritative and emotive. His dramatic range is extensive and he breathes life into the descriptions of the Cyclopean ruins. He clearly conveys the confusion and fear that Dyer feels as he explores the hidden city. This is a concise and well paced adaptation that breaks the story into five parts, with each episode running approximately 33 minutes. It is a very accessible version of Lovecraft’s classic tale and a great point of entry into the Cthulhu Mythos for those who are unfamiliar with it. At the Mountains of Madness is currently available on Audible.

The Silmarillion by J. R. R. Tolkien - Read by Martin Shaw (1998)

Let’s not be coy about this. J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion is not in any way a light read. It has a complex narrative, filled with staggering amounts of lore to digest. I certainly wouldn’t recommend it to anyone as their first point of entry into the Tolkien Legendarium. I think this is a book that you tackle after The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, if you are sufficiently enamoured with the threads of a wider backstory that are alluded to in both those volumes. If that is the case then brace yourself. However, despite its sprawling histories and dense genealogies, The Silmarillion is an incredibly rewarding book. There is an air of majesty surrounding the epic stories it contains and its themes about the eternal struggle between the dark and the light are timeless. Due to the immense detail that Tolkien lavishes upon the text, Middle-earth feels like a genuine living, breathing world. A world of languages, culture, geography and history. To date it has never been equalled.

Let’s not be coy about this. J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion is not in any way a light read. It has a complex narrative, filled with staggering amounts of lore to digest. I certainly wouldn’t recommend it to anyone as their first point of entry into the Tolkien Legendarium. I think this is a book that you tackle after The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, if you are sufficiently enamoured with the threads of a wider backstory that are alluded to in both those volumes. If that is the case then brace yourself. However, despite its sprawling histories and dense genealogies, The Silmarillion is an incredibly rewarding book. There is an air of majesty surrounding the epic stories it contains and its themes about the eternal struggle between the dark and the light are timeless. Due to the immense detail that Tolkien lavishes upon the text, Middle-earth feels like a genuine living, breathing world. A world of languages, culture, geography and history. To date it has never been equalled.

The Silmarillion is the jewel in the crown of J.R.R. Tolkien’s imaginative writing, a collection of narratives ranging in time from the Elder Days of Middle-earth, through the Second Age and the rise of Sauron, to the end of the War of the Ring. The Ainulindalë is a myth of the Creation. In the Valaquenta the nature and powers of the gods is described. Quenta Silmarillion is set in an age when Morgoth was the first Dark Lord and dwelt in Middle-earth. The Elves made war upon him in his impenetrable fortress in Angband for the recovery of the Silmarils. Three jewels containing the last remaining pure light of Valinor, seized by Morgoth and set in his iron crown. The Akallabêth recounts the downfall of the great island kingdom of Númenor at the end of the Second Age. Of the Rings of Power tells of the great events at the end of the Third Age, as told in The Lord of the Rings.

The Silmarillion is a history, albeit an invented one. The book is not linear, nor is it always chronological. It blends expository mythological texts with more traditional story-telling. Despite this structure, it is hard not to feel a sense of awe at the totality of Tolkien’s visions. The book is a prodigious chronicle, highlighting events and individuals with a scope too large to easily summarise. Needless to say, it can often be difficult to keep track of all the characters. Often one story dovetails or impacts upon another, so that it frequently feels like a single narrative rather than a collection of smaller stories. There are events such as the founding of great cities, establishing dynasties, the sundering of peoples and the inevitable waging of war. Throughout these events there is tragedy, beauty, torture, escapes, murders and betrayals. Some characters are noble where others are blighted by hubris, although it often goes ill for them. Although these tales are long and complex, they’re never dull.

The HarperCollins audiobook, recorded in 1998 by British actor Martin Shaw, is possibly the most accessible way for relatively new fans of Tolikien’s writings to tackle The Silmarillion. Shaw narrates with a strong degree of reverence that borders on religious solemnity, guiding listeners carefully through epic battles and epochal events, as well as the legions of protagonists, antagonists and side characters. Shaw skilfully handles the difficult pronunciations of Tolkien's invented languages and inspires a frisson of pleasure when he breaks the straight narration to slip into character voices. The measured pacing of his reading is invaluable to the listener in allowing them to reflect upon the unfolding story and then digest it. I would also recommend listening to this audiobook while having a map of Beleriand to hand. Seeing the geography of the regions discussed is a major asset in understanding the events described. The Silmarillion read by Martin Shaw is currently available on Audible and would make a welcome addition to any Tolkien fan’s library.

Unfinished Tales by J. R. R. Tolkien - Read by Timothy and Samuel West (2021)

First published in 1980, Unfinished Tales is a collection of stories by J. R. R. Tolkien, that spans from the Elder Days of Middle-earth to the end of the War of the Ring. For those who have read both The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings, this book provides additional insights and more detailed accounts of many key events of the First, Second and Third age. Such as Gandalf’s informative tale of how he came to send the Dwarves to Bag-End in search of a burglar, the appearance of the sea deity Ulmo before Tuor on the coast of Beleriand and an in depth description of the military organization of the Riders of Rohan. This collection of stories and essays by J. R. R. Tolkien were never fully completed during the author’s lifetime but were posthumously edited by his son Christopher Tolkien and present with notes, annotations and were required a detailed commentary.

First published in 1980, Unfinished Tales is a collection of stories by J. R. R. Tolkien, that spans from the Elder Days of Middle-earth to the end of the War of the Ring. For those who have read both The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings, this book provides additional insights and more detailed accounts of many key events of the First, Second and Third age. Such as Gandalf’s informative tale of how he came to send the Dwarves to Bag-End in search of a burglar, the appearance of the sea deity Ulmo before Tuor on the coast of Beleriand and an in depth description of the military organization of the Riders of Rohan. This collection of stories and essays by J. R. R. Tolkien were never fully completed during the author’s lifetime but were posthumously edited by his son Christopher Tolkien and present with notes, annotations and were required a detailed commentary.

Unfinished Tales also contains the only stories about the island of Numenor before its downfall, and all that is known about the Five Wizards that made up the Istari. Christopher Tolkien’s notes are invaluable, highlighting any deviations in lore with other books in the Tolkien Legendarium. They also help the reader to grasp the evolution of many of the tales and subject matter and provide a sense of context within the rest of his Father’s writings. The commercial success of Unfinished Tales demonstrated that there was still a strong demand for Tolkien's work after his death and that readers would avidly consume any material that provided further insight into the history of Middle-earth. Encouraged by the result, Christopher Tolkien embarked upon the more ambitious twelve-volume work entitled The History of Middle-earth which encompasses nearly the entire body of his Father's writings about Middle-earth.

This May HarperCollins released a new unabridged audio recording of this seminal text featuring the combined vocal talents of Father and Son, Timothy West CBE and Samuel West. The production is exemplary and the quality of reading outstanding. Both Messr West Senior and Junior, being established actors, navigate the choppy waters of pronouncing names correctly with ease. I would go so far as to say that their combined flawless diction adds immensely to the proceedings. The central narrative is told by Samuel West and his Father Timothy reads Christopher Tolkien’s annotations and notes. Furthermore, they read at a measured pace allowing the listener to digest the narrative which at times can be quite complex. It is a far cry from previous unofficial audio versions which have been read in the most perfunctory fashion and without any degree of enthusiasm. Hence I wholeheartedly recommend this version of Unfinished Tales due to its accessibility and quality.

The Demon-Haunted World by Carl Sagan

“For me, it is far better to grasp the Universe as it really is than to persist in delusion, however satisfying and reassuring.”

The problems that beset the modern world are complicated and nuanced. Thus any potential solutions will be equally complex and subtle. There are no quick fixes for issues such as climate change or nuclear proliferation and anyone trying to sell you one is either a charlatan or a fool. In his book, The Demon-Haunted World, Carl Sagan strongly advocates that adopting a scientific approach to thinking is essential in a modern democracy. By this he means questioning ideas critically and requiring evidence based arguments. If something cannot be effectively measured, tested or verified we should be deeply sceptical of it. He even goes so far as to argue that it is patriotic to ask questions and that any person, institution or organisation that avoids such scrutiny should be deemed suspect. Published in 1995 Sagan’s concerns regarding the coming century have proven sadly accurate. A quarter of a century ago, he predicted the rise of misinformation, fake news and alternative facts. When information is controlled and a population lacks critical thinking it becomes "unable to distinguish between what feels good and what’s true".

“For me, it is far better to grasp the Universe as it really is than to persist in delusion, however satisfying and reassuring.”

The problems that beset the modern world are complicated and nuanced. Thus any potential solutions will be equally complex and subtle. There are no quick fixes for issues such as climate change or nuclear proliferation and anyone trying to sell you one is either a charlatan or a fool. In his book, The Demon-Haunted World, Carl Sagan strongly advocates that adopting a scientific approach to thinking is essential in a modern democracy. By this he means questioning ideas critically and requiring evidence based arguments. If something cannot be effectively measured, tested or verified we should be deeply sceptical of it. He even goes so far as to argue that it is patriotic to ask questions and that any person, institution or organisation that avoids such scrutiny should be deemed suspect. Published in 1995 Sagan’s concerns regarding the coming century have proven sadly accurate. A quarter of a century ago, he predicted the rise of misinformation, fake news and alternative facts. When information is controlled and a population lacks critical thinking it becomes "unable to distinguish between what feels good and what’s true".

Presented as a collection of essays The Demon-Haunted World can be read in a linear fashion, or you can select specific chapters as each is broadly self contained. Sagan recounts his own relationship with science in the fifties and sixties and how it enthused him, especially when he learned how to think critically and reason for himself. He then focuses on how such skills are conspicuously absent from Western teaching curriculums, leaving us with a society that is unable and at times unwilling to think independently. He reflects upon how knowledge and academia are often seen as elitist and “uncool”. However, he remains empathetic and non-judgemental throughout, advocating that people are not too stupid too learn but that society has instilled in them a mindset that they can’t, as it’s too hard. Hence he addresses the allure of pseudoscience, horoscopes, crystals, conspiracy theories and his analysis shows that they’re similar to the superstitions that were prevalent in the past.

"The dumbing down of American is most evident in the slow decay of substantive content in the enormously influential media, the 30 second sound bites (now down to 10 seconds or less), lowest common denominator programming, credulous presentations on pseudoscience and superstition, but especially a kind of celebration of ignorance.”

In fact Sagan is incredibly generous in his assessment of many examples of science-woo. He acknowledges that they come from a desire to know the universe and that the methodology is what leads to incorrect conclusions. Another argument he explores is that societal change, especially the move from an industrial economy to a more information based model means that power and decision making is centralised into the hands of smaller groups. This can lead to people refraining from asking questions per se because religious, political, scientific and technological authorities do all the heavy lifting for us. The resultant information is then refracted through the prism of a small group of closely aligned and partisan media that have a monopoly on communication platforms. However, applying the scientific method to our daily thinking is a way to break this cycle.

After forensically dissecting such subjects as possessions, demons, UFOs and reincarnation The Demon-Haunted World then addresses issues stemming from science itself. The misuse and morality of science, especially the misuse of psychiatric authority. It is to Sagan’s credit that he is comfortable applying the same scepticism to both pseudoscience and science itself. But perhaps the best parts of the book and when he offers a simple set of processes that are beneficial to adopt when pondering weighty subjects. What he calls the “baloney detection kit”. Nine intellectual tools, such as Occam’s Razor, to test the validity of a premise, idea or more importantly, political statement. Again it is important to stress that Sagan teaches compassionately, unapologetically and poetically how to ask questions for yourself. He is reassuring and encouraging and not as didactic as one may assume.

“Science is an attempt, largely successful, to understand the world, to get a grip on things, to get hold of ourselves, to steer a safe course. Microbiology and meteorology now explain what only a few centuries ago was considered sufficient cause to burn women to death.”

It is the book’s tone that is a constant delight, considering the weighty and somewhat dry nature of the subject of science based critical thinking. I am a great admirer of Richard Dawkins but although a fine thinker, he is not the diplomat and people person that Sagan was. The unifying ideal that Sagan continuously returns to is the search for answers from all quarters of society, be they scientific or not. However he clearly highlights the failings of contemporary western education and how we are not taught to ask questions. Instead we are told what the current accepted wisdom is and what must be done to arrive at the correct conclusion. He is particularly scathing of the US being a result oriented society, obsessed with grades along with an erroneous concept of what achievement actually is. Furthermore he is mindful of how this coupled with indifferent thinking puts both democracy and freedom at risk. And again, Carl Sagan deduced all this twenty five years ago.

The Demon-Haunted World is a book about finding a sense of wonder in life and that science driven, critical thinking does not diminish that. Sagan was a great communicator and he makes some of the more complex scientific ideas as accessible as they can be made. However, as a scientist he does like to cite multiple examples to illustrate and validate his points, so this is a book that requires focus. Therefore the chapter by chapter approach can serve well. I tackled this book via an audio version, featuring unabridged readings by Cary Elswes, Seth McFarlane, LeVar Burton and Carl Sagan’s wife, Ann Druyan. Overall, I feel that this is one of the most profound and thought provoking books I’ve experienced in recent years. It does highlight growing causes for concern but it also provides a sense of hope. I believe that the scientific method not only equips us as a society to tackle the major issues facing the world but that it can also make us more effective citizens. By questioning and assessing what those in authority advocate, we can determine the validity and rectitude of their claims.

“Claims that cannot be tested, assertions immune to disproof are veridically worthless, whatever value they may have in inspiring us or in exciting our sense of wonder.”

Audiobooks

In my youth I was a prodigious reader. I spent many a happy weekend visiting my local library and often spent my pocket money on books as a child. Overtime, I changed from reading fiction to non-fiction. More recently, a lot of my reading has been done online, consumed either via my office PC or tablet. That’s not to say that I don’t buy paperback or hardback books anymore. I still consider this to be the preferred experience. There is something fundamentally exciting about sitting down in a comfy chair, reading at your own pace, away from distractions. However last year I injured my left arm and I have subsequently found holding a large hardback book to be a difficult experience. So for the sake of convenience I started listening to audiobooks instead. I’ve always enjoyed them considering them a great alternative to traditional print media. What my recent foray into this format has taught me is how much the medium of the audiobook has grown.

In my youth I was a prodigious reader. I spent many a happy weekend visiting my local library and often spent my pocket money on books as a child. Overtime, I changed from reading fiction to non-fiction. More recently, a lot of my reading has been done online, consumed either via my office PC or tablet. That’s not to say that I don’t buy paperback or hardback books anymore. I still consider this to be the preferred experience. There is something fundamentally exciting about sitting down in a comfy chair, reading at your own pace, away from distractions. However last year I injured my left arm and I have subsequently found holding a large hardback book to be a difficult experience. So for the sake of convenience I started listening to audiobooks instead. I’ve always enjoyed them considering them a great alternative to traditional print media. What my recent foray into this format has taught me is how much the medium of the audiobook has grown.

As an Amazon Prime customer the most immediate port of call for audiobooks is the Audible service. There is a 30 day trial which gives you 1 credit, allowing you to purchase for free any available title. This is particularly beneficial as you can choose a new release if you see fit. Of course other providers are available and should not be overlooked. After my trial expired I was offered a further discount if I continued as a subscriber, which I accepted. The terms were favourable. Hence since last November I have acquired 5 audiobooks and only spent £12. There’s always a deal to be had and Amazon would rather have some of your money rather than none. The books can be downloaded and accessed whether you are currently subscribing or not and played on a variety of platforms. I find the seamless integration with the Amazon Echo very useful. I also like the feature where you can continue listening from where you previously finished, across multiple devices.

Although I enjoy reading for myself, I also like being read to. I think the key to a good audiobook is finding an appropriate narrator. If this is done correctly, then an audiobook becomes a far more satisfying experience. I would also argue that the sharing of stories touches something very primeval within us and elicits not only an intellectual response but something very emotional as well. There are other benefits to audiobooks as well. For example when listening to the works of J.R.R. Tolkien it is interesting to hear the correct pronunciation of the various languages. Also, leisurely paced narration that follows the punctuation correctly, allows the listener to ponder and digest what they’re listening to. And then there is the calming quality of certain narrators who bring an additional quality to the proceedings due to their dulcet tones.

At present my listening tastes favour non-fiction. I like material that makes you think and has a degree of factual and intellectual rigour. Hence I have listened to the following over the last 4 months:

How Not to Be Wrong: The Art of Changing Your Mind by James O'Brien.

Politically Homeless by Matt Forde.

How to Be a Liberal: The Story of Liberalism and the Fight for Its Life by Ian Dunt.

I'm a Joke and So Are You: Reflections on Humour and Humanity by Robin Ince.

The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark by Carl Sagan.

All of these have been very rewarding and food for thought. All except the Carl Sagan book are read by their respective authors.

Libraries

If you wanted to find me on a Saturday afternoon during the late seventies and early eighties, then the local library was a safe bet. At one point I belonged to three including one in a neighbouring borough but Blackfen Library was my favourite. It was the nearest to our home and I was fond of the oddly austere building. Both of my parents have always been prodigious readers so going to the library quickly became a regular part of my youth. Initially, I was content to confine myself to the children’s section reading Hergé's Adventures of Tintin and the escapades of Asterix the Gaul. However, I was never really content with fiction aimed at children and especially stories about children. Hence as I grew older I expanded my horizons and strayed into the adult section. My parents didn’t interfere in my choice of books and took the attitude that if I were reading, then I wasn’t getting into trouble. My Dad would make the occasional recommendation. Usually classic science fiction by authors such as Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke.

Blackfen Library prior to it’s relocation in 2004

If you wanted to find me on a Saturday afternoon during the late seventies and early eighties, then the local library was a safe bet. At one point I belonged to three including one in a neighbouring borough but Blackfen Library was my favourite. It was the nearest to our home and I was fond of the oddly austere building. Both of my parents have always been prodigious readers so going to the library quickly became a regular part of my youth. Initially, I was content to confine myself to the children’s section reading Hergé's Adventures of Tintin and the escapades of Asterix the Gaul. However, I was never really content with fiction aimed at children and especially stories about children. Hence as I grew older I expanded my horizons and strayed into the adult section. My parents didn’t interfere in my choice of books and took the attitude that if I were reading, then I wasn’t getting into trouble. My Dad would make the occasional recommendation. Usually classic science fiction by authors such as Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke.

Despite it’s somewhat foreboding appearance, Blackfen Library was always warm and tranquil inside. The library ticket system was uncomplicated. Your ticket was a small cardboard pocket. Each book had a physical ticket associated with it which was filed along with your ticket when you borrowed it. Inside the cover of each book was a “date due” sheet which was stamped by the librarian with the return date. I believe you could keep your books for up to three weeks and borrow a maximum of six. As this was the seventies, the books were filed and organized using the Dewey Decimal System. I quickly learned to use this so I didn’t have to rely on the librarians to assist me. Choosing my books was always an exciting process. Sometimes I’d know in advance what I wanted and I’d race in between the heavy wooden bookshelves to the required section to see if my prize awaited. Other times I’d peruse the shelves in a leisurely fashion, reading the plot synopsis on the dust covers. They say not to judge a book by its cover but when you’re 10 years old, a glossy illustration by Chris Foss or Frank Frazetta was a major selling point.

Classic science fiction with Chris Foss artwork

Due to my parents and my local library, I still have a deep and abiding love for books and reading. One of my favourite excursions (pre-lockdown) is to travel to Rochester in Kent and lose myself in Baggins Book Bazaar, the biggest second hand bookshop in the UK. It has many similarities with a library and is a haven of tranquility in an otherwise noisy and frenetic world. Sadly, the original Blackfen Library in Cedar Avenue has now closed and the building was demolished and the land sold to a property development company in 2004. There’s a block of flats on the site now. The library has relocated to new premises in Blackfen Road. It has diversified and modernised in an attempt to stay relevant. It now has internet access and PCs that you can use. The premises also offer several meeting rooms and run numerous clubs and activities. It’s now a bustling and dynamic place. It’s all a far cry from the black and white tiled floors and quiet atmosphere of the former site.

As you may discern, I believe passionately in libraries and making books, knowledge and learning accessible to all. The ability to read is not only a great leisure activity and escape from the rigours of life but it’s also an opportunity for self improvement and to expand one's horizons. Which is why I greatly resent and deplore the closure of over 800 public libraries that have happened since 2010 in the UK. A recent survey from the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (Cipfa) has found that there are 3,583 public libraries open at present. 35 fewer than last year and 773 fewer than in 2010. The closure of nearly a fifth of the UK’s libraries is a result of a decline in spending by 29.6% over the past decade. The reduced funding is due to the UK government cutting spending on all public services after the banking crash of 2008. The debate continues as to whether this was necessary or driven by political ideology. I believe author and comedian Alexei Syale may have some insight when he said “austerity is the idea that the 2008 financial crash was caused by Wolverhampton having too many libraries”.

Blackfen Library as of 2020

I am a child of the seventies and although I won’t universally extol the merits of that decade, it did have some good points from a child’s perspective. Blackfen Library introduced me to the joys of H. G. Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, J. R. R. Tolkien and many other classic authors. It also taught me that silence is not to be feared but something to be savoured when appropriate. Like most adults, as I’ve got older I find that I don’t read as much as I used to, although I still manage a book each month or so. Reading for me now centres on blogs and other online news outlets. But I still enjoy finding a quiet corner and losing myself in a good book. And I still visit my local library (which have now reopened) although now it tends to be more when they hold events. But it is important that we as a society fight any further closures and continue to foster in our children the importance and pleasure of reading. Although I suspect this will be more of an uphill struggle in the current political climate.

Geekpriest: Confessions of a New Media Pioneer by Fr. Roderick Vonhögen

The gaming community (as well as many others) can be somewhat myopic at times. I'm sure many people are aware of Father Roderick and his prolific body of work. Is there a game, genre movie, TV show or some form of technology that he doesn't cover on his various podcasts and YouTube videos? Yet outside of this environment, his championing of all things "geek" still comes as a culture shock to the wider world with their somewhat entrenched attitudes towards both the “nerdy” and the religious. His 2013 book Geekpriest: Confessions of a New Media Pioneer, endeavours to address this issue. Furthermore it clearly advocates that the church should embrace all forms of new media and engage with all communities. Fandom, shared interests and hobbies are a great starting point for this.

The gaming community (as well as many others) can be somewhat myopic at times. I'm sure many people are aware of Father Roderick and his prolific body of work. Is there a game, genre movie, TV show or some form of technology that he doesn't cover on his various podcasts and YouTube videos? Yet outside of this environment, his championing of all things "geek" still comes as a culture shock to the wider world with their somewhat entrenched attitudes towards both the “nerdy” and the religious. His 2013 book Geekpriest: Confessions of a New Media Pioneer, endeavours to address this issue. Furthermore it clearly advocates that the church should embrace all forms of new media and engage with all communities. Fandom, shared interests and hobbies are a great starting point for this.

One of the reasons I enjoyed Geekpriest: Confessions of a New Media Pioneer so much is because I am of a similar age group to Father Roderick and have shared many of the same aspects of pop culture while growing up. The impact that Star Wars had upon most children of the seventies is succinctly explored within the book. The love of specific TV shows and the importance of certain science fiction and fantasy authors will chime with many readers. The passion these things instilled in so many of us is clearly present in the text. It is through the love of these common interests that Father Roderick manages to dispel so many misconceptions about the clergy. It makes him very accessible and relatable, which is a major theme of the book.

What becomes apparent very quickly is Father Roderick’s practical and sincere approach to evangelism. Evangelism is something that many people of faith feel compelled to undertake but often mishandle. Geekpriest: Confessions of a New Media Pioneer shows a means of engaging with others through shared interest, winning trust and respect and then being in a better position to explore religious belief. The common sense of such an approach is irrefutable. Too often faith is separated from real life and placed in a remote ivory tower or framed in terms of academia. It's perceived formality can be intimidating. Yet here we have a priest who can happily talk to you about playing MMOs and wiping in a raid, or how the latest entry in the MCU is either perfunctory or awesome.

Geekpriest: Confessions of a New Media Pioneer is a very accessible book, written in an informal and engaging way. It gives a great insight into Father Roderick's life and clearly shows the importance of new media, not only to the church but in all walks of life. We learn of his love of all things geeky and how his passion for the works of Tolkien and J.K. Rowling among so many other things, made him an internet hit. Cookery and personal health are other excellent examples of how he engages with people. Overall, Geekpriest: Confessions of a New Media Pioneer is an accessible read irrespective of your stance on faith. At the very least its fundamental message of getting to know people through shared interests is one that bears repeating. We are all so quick to pigeon hole each other and segregate ourselves these days, that we often forget about the things that unite us.

Ten Books of Note - A Personal Selection

Many of my fellow bloggers regularly posts details of what they’ve been reading of late. I must admit that although I received several books and graphic novels as Christmas presents, I’ve yet to start any of them. The bulk of my reading is done via my PC or Tablet and usually tends to be news articles, blog posts and research for my writing. The last book that I physically read was Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea & Elysia by Brian Lumley and that was last November. So, I’ve decided to get back into reading in the traditional sense and as ever have allotted time in my schedule and set myself goals. As a carer I have numerous appointments to attend throughout the week with my parents. Rather than waste time on my phone perusing twitter and gawping at the internet, I shall use these periods to read.

Many of my fellow bloggers regularly posts details of what they’ve been reading of late. I must admit that although I received several books and graphic novels as Christmas presents, I’ve yet to start any of them. The bulk of my reading is done via my PC or Tablet and usually tends to be news articles, blog posts and research for my writing. The last book that I physically read was Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea & Elysia by Brian Lumley and that was last November. So, I’ve decided to get back into reading in the traditional sense and as ever have allotted time in my schedule and set myself goals. As a carer I have numerous appointments to attend throughout the week with my parents. Rather than waste time on my phone perusing twitter and gawping at the internet, I shall use these periods to read.

In the meantime, I thought I’d kill two birds with one stone and not only set up a reading schedule but write a quick list of some of my favourite books. I would like to stipulate that this is not a "top ten" or a list of books of outstanding literary merit, although I believe some of these titles do fall into the latter category. These are simply books that I've enjoyed reading and that made quite a big impact upon me at the time. All the titles discussed in this post are works of fiction. I’ll more than likely compose a separate list for non-fiction titles. For the record, I have no particular preference for either genre. The only thing I require from a book is that it’s absorbing. A book that cannot hold my interest is soon cast aside.

The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway: I first read this book when I was fifteen and it was the one of the set texts for an exam. I was left bewildered by the themes that the story explores and frankly had little sympathy for the "Old Man". Having re-read in more recent years I now find many of the concepts far more accessible. Santiago's struggle with his Marlin adversary is quite profound and I no longer see the books ending as a failure but a positive validation of the "Old Man" motives.

Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell. Orwell's vision of the future is possibly more relevant today than it was upon its publication in 1949. "Doublespeak" along with "Two Minutes of Hate" seem to be integral aspects of modern life and we seem to have willingly embraced them, rather than had them forced upon us. For me the most powerful aspect of the book is the bleak but utterly plausible ending. I think this book should be mandatory reading in all schools.

The Lord of the Rings by JRR Tolkien: I read The Hobbit as a child but didn't tackle The Lord of the Rings until 1978. I find the depth of history that permeates the text extremely engaging. Even though the events of the third age feel epic, there is still a sense of something even vaster reaching back over time. There are also many thought provoking themes within the narrative and the book holds up to multiple readings, due to its complexity. I am still intrigued by the enigma of Tom Bombadil. This is a book that manages to be many things to many people, finding fans and enthusiasts from all quarters. I like that quality.

The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens: A timeless tale of a group of gentlemen and their misadventures as they travel around the English countryside. As well as being a very interesting snap shot of travel in Dickensian times, this is a genuinely funny collection of stories reflecting the fact that human nature seldom changes over time. This book was instrumental in kindling my love of language. Dickens uses some wonderful words and phrases, many of which I have adopted into my personal lexicon.

At the Mountains of Madness by H.P. Lovecraft: A superb tale that blends both science and the supernatural. Set in a time when the world still held hidden mysteries and vast swathes of the earth remained unexplored, this is a disquieting tale, that builds in atmosphere. Lovecraft's skill lies in exploring the concept of something vast and ancient that lurks just beyond our normal senses. He excels at conveying the idea that we unknowingly share time and space with ancient beings, utterly alien to ourselves. This book is a great introduction into the world of the Cthulhu Mythos.

The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury: Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles is a thoughtful, lyrical collection of short stories about human colonisation of Mars and its consequences it has upon both races. Filled with rich themes and philosophical questions this remains an incredibly thought provoking read. The brief and esoteric insights the stories provide into Martian culture and society are one of the most engaging aspects of the book. The Martian Chronicles is also a snapshot of the prevailing social issues at the time it was written. Many still remain unresolved to this day.

Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K. Jerome: First published in 1889, Three Men in a Boat is a humorous account by Jerome K. Jerome of a boating holiday on the Thames between Kingston and Oxford. Some humour simply doesn't date and this book is filled with amusing vignettes and comic narrations. Two outstanding incidents are Uncle Podger's attempt at hanging a picture and a curious discussion of "Advantages of cheese as a travelling companion". The undertaker’s comments will remain with me forever. What I like about this book is the fact that the indolence of young men remains constant.

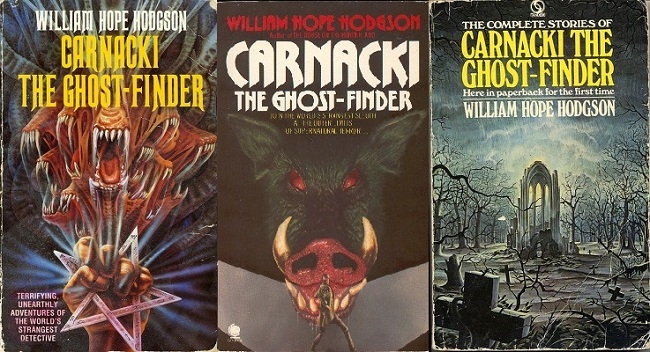

Carnacki the Ghost Finder by William Hope Hodgson: William Hope Hodgson's supernatural detective, Thomas Carnacki, remains criminally underrated in literary circles. This collection of short stories explores several of Cranacki's old cases. Sometimes there are worldly explanations to the various mysteries. Other times there is clear evidence of the opposite. Like Lovecraft, Hodgson hints at a vast, malevolent force outside of human perception. He also mixes science with the occult, with Carnacki frequently using his Electric Pentacle; a series of multicoloured neon tubes. This is weird and baroque fiction at its best.

Twinkle, Twinkle, Killer Kane by William Peter Blatty: Col. Vincent Kane arrives at a remote castle serving as an insane asylum for U.S. Army soldiers where he attempts to rehabilitate them by allowing them to live out their fantasies. It soon becomes apparent that Kane may be just as psychologically disturbed as his patients. Fascinating, tragic and immensely uplifting are just some of the ways I would describe this book. It manages to balance a compelling theological subtext with a strong streak of gallows humour. A very rewarding read and one of the great unsung novels of the seventies.

The Medusa Touch by Peter Van Greenaway: On the surface this is quite a conventional science fiction potboiler, about a disenfranchised writer who has the power to create disaster and catastrophe. However, it is elevated above the mundane by the central character of John Morlar, whose misanthropic narratives are utterly fascinating and sadly quite perceptive. The book also raises some relevant questions about the establishment, various public institutions and their relationship with power, which was a common theme for the author. The cathedral shattering denouement is suitable spectacular.

So, there are ten books that I recommend. As of tomorrow, I embark upon my new reading regime. For my first book of 2017, I’ve opted for some heavyweight non-fiction. I’ve ordered Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari. I heard the professor being interviewed on a podcast recently and he raised several points about human nature that I found fascinating. So, I’ll give one of his books a go. If it proves too taxing or beyond my intellect, then I have several short stories by Roger Hargreaves in reserve. His work never fails to delight. In the meantime, feel free to leave a comment and recommend anything you’ve read that you think may be of interest to me.

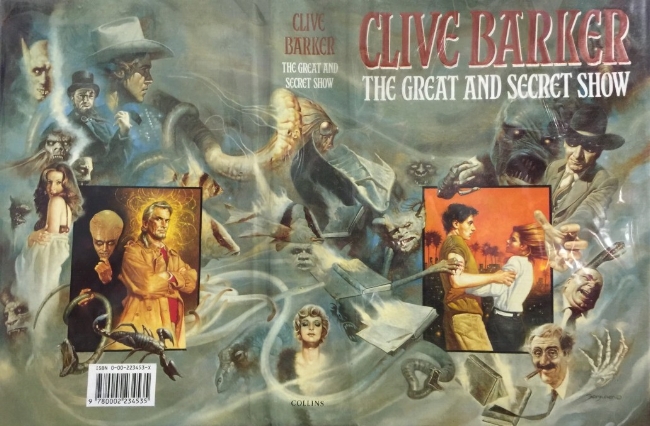

The Great and Secret Show by Clive Barker (1989)

During the eighties, I was an avid fan of the novelist Clive Barker. I consumed all his work voraciously and sought out magazine and television interviews with him whenever I could, finding the man equally as fascinating as his work. Oh, to be a twenty something horror fan during the genre renaissance of that decade. Despite the yolk of the Video Recordings Acts and the scaremongering of the tabloid press over “Video nasties”, horror fiction both in print and on the big screen was elevated to new levels due to the creativity of one British author and director. These were halcyon days for fan boys and girls.

During the eighties, I was an avid fan of the novelist Clive Barker. I consumed all his work voraciously and sought out magazine and television interviews with him whenever I could, finding the man equally as fascinating as his work. Oh, to be a twenty something horror fan during the genre renaissance of that decade. Despite the yolk of the Video Recordings Acts and the scaremongering of the tabloid press over “Video nasties”, horror fiction both in print and on the big screen was elevated to new levels due to the creativity of one British author and director. These were halcyon days for fan boys and girls.

In August 1989 Clive Barker released his fifth major novel, The Great and Secret Show. Expectations among fans were high as they prepared themselves for another cerebral, densely plotted and philosophical tale. Barker has always had a gift for characters and is an author that doesn’t give his readers everything on a plate. You have to bring your imagination and intellect with you when you read his work. Let other’s sit around and debate Proust or Kafka. We had Clive Barker who provided not only comparable brain food but did so via the medium of the horror genre. Such work provided a great opportunity for fans to pose, get their fix and stroke their beards.

Naturally there was a various book signings across the UK to promote the new book. My memory is a little vague here but I believe an autumn appearance at The Forbidden Planet in London offered me the best opportunity to meet Clive Barker. However, something came up unexpectedly and I was unable to attend the signing, so my friend Paul went alone, entrusted with a vital message like R2-D2. I awaited eagerly at home pondering how my thoughtful and penetrating question would be greeted by the great author. What words of wisdom would I be given in return? How the hubris of my youth still haunts me to this day.

When I next met with Paul, I was presented with a first edition copy of The Great and Secret Show. To my surprise, Paul did not convey to me verbally, the reply Clive Barker had made to my probing enquiry or regale me with a lengthy anecdote about his experience. He simply opened the book, presenting me with a hand-written inscription from the author himself. I remember being utterly stunned that Clive Barker himself had not only written a personal message but had addressed my point head on, in a succinct and candid fashion. To this very day, I’m still impressed that he took the time to do this. I think it speaks volumes about the man and his approach to fans and life.

Today as I was going through some storage crates, searching for a specific book, I found my copy of The Great and Secret Show. Naturally this whole story came flooding back and I found myself reminiscing about not only these specific events but the entire horror scene at the time. They were happy days. But I digress. Here finally is a picture of the very inscription that Clive Barker wrote. It just remains for me to tell you exactly what it was that I had asked by proxy. My question was simply this. “Why was Hellbound: Hellraiser II so shit?” Clive’s answer, as you can see, is magnificent.

Twenty-seven years on I find myself both older and little wiser. I still consider Clive Barker to be one of the best writers of those times. I also have enormous respect for the way he treats his readers and audience. I know he’s had some bad experiences in the past and I’m amazed he found the good humour to deal with such a crass and puerile enquiry such as mine. If I were ever to meet him in the future I like to think I’d ask him something a little more respectful and interesting this time round. They say that fans shouldn’t meet their heroes. However, I believe there’s something to be said about the reverse. I’ll let you ponder that while I re-read The Great and Secret Show.

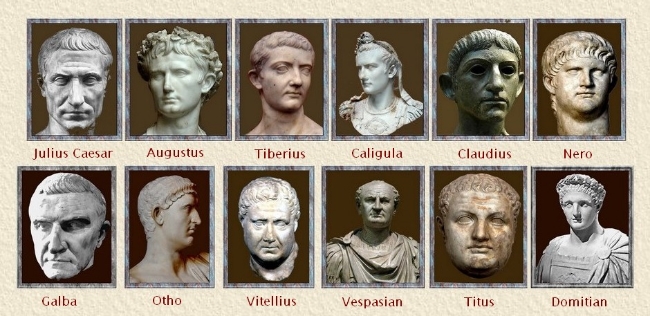

The Twelve Caesars by Suetonius

Many people consider history (or at least books about it) to be a dry and a somewhat dull experience. If you are such a person then I cordially invite you to think again. Suetonius’ book “The Twelve Caesars” is a catalogue of degeneracy, perversions and general behaviour that would upset the vicar. It is both gripping and informative, proving that with regard to human nature, no matter how things change, they remain the same.

Many people consider history (or at least books about it) to be a dry and a somewhat dull experience. If you are such a person then I cordially invite you to think again. Suetonius’ book “The Twelve Caesars” is a catalogue of degeneracy, perversions and general behaviour that would upset the vicar. It is both gripping and informative, proving that with regard to human nature, no matter how things change, they remain the same.

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillis was born in A.D. 69. He became a scribe in the service of Hadrian, who was emperor from A.D. 117-138. Having been dismissed for ‘indiscreet behaviour’ with Hadrian’s empress, Sabina, he turned his hand to several books regarding history and philosophy. These received a lukewarm reception among classical scholars, but the ‘The Twelve Caesars’ has proved otherwise. Its mixture of scholarly facts along with tabloid scandal-mongering is the key to its broad appeal.

The most well-known translation of the source text is by Robert Graves, who used this as the basis for his own novel “I, Claudius”. This translation is not linguistically verbatim but rather a faithful account of Suetonius work, rendered into Standard English. This makes the book extremely accessible. Although there are editorial notes, they do not impede the narrative allowing the reader to approach the material as either a scholar or a voyeur.

Suetonius is not coy about the peccadilloes of the emperors and their families, nor does he hold back in his moral judgement of them. So we get details about Julius Caesar the catamite of King of Bithnyia (Yes, it wasn’t a term I was familiar with either. Google is your friend), Augustus singeing off his leg hair with hot walnut shells and Nero having the entrances barred so people could not leave his poetry recitals. One lady gave birth during such an event. There’s also rape, murder, torture, incest, more torture, more murder, all kinds of killing of family members, bestiality and interpretive dance.

It’s compelling stuff and even more so when you consider the text is not far off being two thousand years old. Suetonius’ “The Twelve Caesars” is constructed in such a way as to be extremely accessible. This can be read whilst commuting, at home in an armchair or on the beach on holiday. The latter may even increase your credibility as an intellectual. It also serves as a lesson about the nature of power. Be grateful that our contemporary leaders do not wield such arbitrary life or death powers.

James Bond Novels

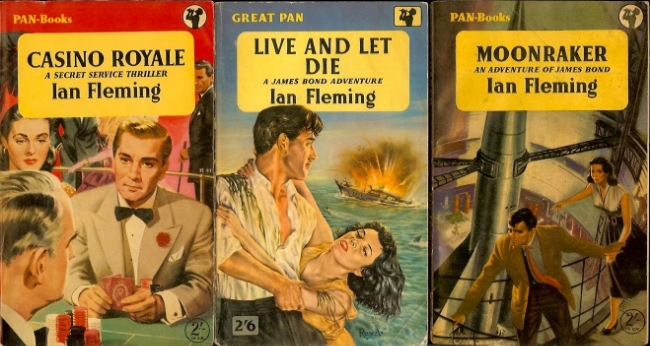

I recently started reading fiction again after spending half a year focused upon academic subjects and ploughing my way through numerous non-fiction books. I’ve always been a fan of the Bond franchise so decided it was time to familiarise myself with Ian Flemings’ the source material. The results so far have proven to be quite surprising and not at all as I expected. I managed to purchase the first seven novels in the series from a second hand book shop and have so far completed five of them. I also have audio book version available of the all of Fleming’s stories should I need to consume them in such a fashion.

I recently started reading fiction again after spending half a year focused upon academic subjects and ploughing my way through numerous non-fiction books. I’ve always been a fan of the Bond franchise so decided it was time to familiarise myself with Ian Flemings’ the source material. The results so far have proven to be quite surprising and not at all as I expected. I managed to purchase the first seven novels in the series from a second hand book shop and have so far completed five of them. I also have audio book version available of the all of Fleming’s stories should I need to consume them in such a fashion.

One of the first things that stands out when reading Fleming’s novels, is how the books notably vary from the films. The stories are often quite minimalist and not especially as epic in scope as the movies. The content is often quite adult and very much reflects the mood and prevailing sensibilities of the times. Remember that Fleming created these books during the 1950s which were a particularly hard time for the United Kingdom. The country was virtually bankrupt and dealing with the demise of its Empire. America was in ascendancy, both politically and economically and the Cold War dominated international foreign policy.

The Bond franchise focuses of many things that would appeal to the reading public of the time; namely the glamour and opulence that was missing from their lives. Fleming is a master at describing exotic foreign travel, fine cuisine and “playboy” lifestyle. The depiction of sexual activity is quite candid for the times, although it betrays the patronising attitude prevalent to women during that era. There are also a lot of themes that will strike today’s reader as simply xenophobic and racist. Context in key in not allowing such elements to impair ones enjoyment..

“Casino Royale” and “Live And Let Die” are both fairly straight forward thrillers. The events are far from incredulous and the stories progress at a rapid pace. The use of violence is striking and well written. Bond being tortured by having his genitals beaten still has the power to shock. But it is not until “Moonraker” that the books truly hit their stride. The storylines have become a little more complex and you feel that this is the Bond that you remember. “Diamonds Are Forever” and “From Russia With Love” further demonstrate this. The style is very compelling and the characters are well defined. The locations and organisations that feature are meticulously researched. Fleming shows a knack for maintaining tension.

The modern spy or espionage novels owe a tremendous amount to the legacy of Ian Fleming. His own experiences in Naval Intelligence and as a journalist afforded him the ability to create credible and absorbing stories. His own personality trait, such as his penchant for women and the “bon viveur” lifestyle, permeates his writing. For British readers enduring the hardship of the post-war austerity years, he gave glimpses of the world beyond their shores and a lifestyle they could only dream of.

It may be difficult for modern readers to connect to the world in which Bond exists, as it is now removed by several generations. It lacks a lot of the technology that people now associate with the franchise due to the movies. The books also showcase a lot of social conventions and geo-political outlooks that contemporary audience may struggle to identify with. However for those who are prepared to look beyond these points, and embrace the culture of the times, Fleming work provides an intriguing insight into post-colonial Britain that has long gone. He also still offers robust and entertaining spy yarns, especially in the later novels.

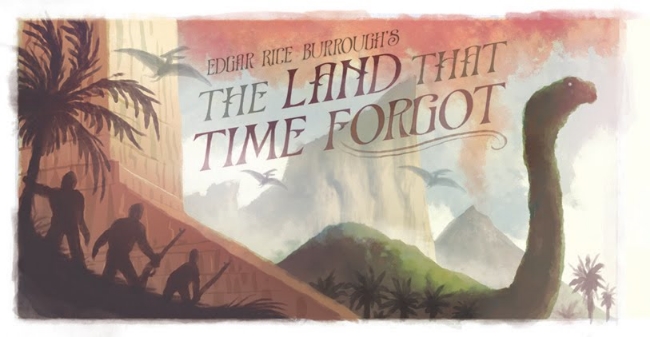

The Land That Time Forgot by Edgar Rice Burroughs (1924)

The Land That Time Forgot is the first part of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ “Caspak” trilogy of science fantasy novels. Commencing as a wartime sea adventure, hence its original working title of The Lost U-Boat, Burroughs’ story ultimately develops into a saga with similarities to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World and Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island. What makes Burroughs work unique is his plot device of a biological system specific to his island, in which the slow progress of evolution manifests itself as individual metamorphosis. This biological feature is only implied in The Land That Time Forgot and explored in greater depth over the course of the next two novels, The People That Time Forgot and Out of Time’s Abyss.

The Land That Time Forgot is the first part of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ “Caspak” trilogy of science fantasy novels. Commencing as a wartime sea adventure, hence its original working title of The Lost U-Boat, Burroughs’ story ultimately develops into a saga with similarities to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World and Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island. What makes Burroughs work unique is his plot device of a biological system specific to his island, in which the slow progress of evolution manifests itself as individual metamorphosis. This biological feature is only implied in The Land That Time Forgot and explored in greater depth over the course of the next two novels, The People That Time Forgot and Out of Time’s Abyss.