Der Tiger AKA The Tank (2025)

On the Eastern Front in 1943, a German Tiger tank crew led by Lieutenant Philip Gerkens (David Schütter) is sent on a mission to rescue the missing officer Paul von Hardenburg (Tilman Strauss) from a top-secret bunker that is at risk of falling into enemy hands. As they make their way through an eerie no-man’s land, they have to avoid Russian armoured vehicles that seem to be aware of their mission. They also encounter a German unit taking punitive action against a peasant village, in reprisal for partisan activity in the area. The youngest crew member, Michel (Yoran Leicher), talks of the land being home to ghosts and spirits. As the tank penetrates further into contested territory the crew become increasingly disturbed by the uncanny nature of their mission and begin to fall prey to their own inner fears.

On the Eastern Front in 1943, a German Tiger tank crew led by Lieutenant Philip Gerkens (David Schütter) is sent on a mission to rescue the missing officer Paul von Hardenburg (Tilman Strauss) from a top-secret bunker that is at risk of falling into enemy hands. As they make their way through an eerie no-man’s land, they have to avoid Russian armoured vehicles that seem to be aware of their mission. They also encounter a German unit taking punitive action against a peasant village, in reprisal for partisan activity in the area. The youngest crew member, Michel (Yoran Leicher), talks of the land being home to ghosts and spirits. As the tank penetrates further into contested territory the crew become increasingly disturbed by the uncanny nature of their mission and begin to fall prey to their own inner fears.

If you watch Der Tiger AKA The Tank expecting to see a film similar to Fury, then you’ll possibly be disappointed. This is not a traditional war film and it doesn’t take long for the story to stray out of one genre and into another. Perhaps the marketing for this film should have been more specific and indicated that it wasn’t just the wartime story of a Tiger tank crew but something a little more “horror adjacent”. That being said, there is much to like about the film and its production. It is beautifully shot by cinematographer, Carlo Jelavic, who imbues a great deal of atmosphere with evocative lighting. The visual effects both physical and CGI are well realised with the Tiger tank being very plausible. The central performances by the actors portraying the five man crew members are strong. Plus, it is always interesting to see WWII from a perspective other than the Allies.

Yet despite so many good elements, director Dennis Gansel, plays his hand too early in the proceedings tipping off astute viewers as to where the film is really heading. To discuss this in-depth would be a spoiler so I shall not go into further detail. As for those who miss this clue, they run the risk of being disappointed in the climax of the third act when the plot takes a radical change. It’s odd that such a clumsy clue was given and I wonder if it was something imposed upon the production by Amazon Studios. Some streaming companies have a policy to accommodate viewers whose attention is divided between watching TV and their smartphone. Whether that is the case here, remains to be seen. However if it is, then it is a sad indictment of contemporary audiences.

As it stands, Der Tiger is a well made exploration not only of the horrors of war but of being lost in grief. The action scenes are tense and well handled, including an interesting encounter with a Soviet SU-100 tank destroyer. The replica Tiger I is in fact a modified T-55 chassis with an aluminium shell built over it. Overall it is very convincing. The story follows a three act arc, starting as a WWII drama, then transitioning into a homage to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. The third act is bold and its credibility ultimately comes down to whether the viewer wishes to maintain their suspension of disbelief and go with the story or not. Some critics have compared Der Tiger with the 2012 Russian film, White Tiger. I would argue that is not a fair comparison because the latter makes it clear that it is a parable right from the start. I enjoyed Der Tiger but recognise that it may not be for everyone.

Treasure Island (1990)

Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic novel has been adapted for cinema and television numerous times. Perhaps the most well known is the 1950 Disney version, starring Robert Newton as Long John Silver. His eye rolling performance and exaggerated West Country accent is credited with popularising the stereotypical form of “pirate speech" that has become the pop culture default. Although an enjoyable film, it does gloss over the more sinister aspects of both the source text and history, perpetuating the myth that pirates are just loveable scoundrels. Many subsequent adaptations have fallen into the same trap to a greater or lesser degree. However, that is not the case with the 1990 version of Treasure island, which was made for the TNT cable network and released theatrically outside of the US. This darker and notably more violent adaptation closely follows the source text and is widely considered the most faithful to the book.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic novel has been adapted for cinema and television numerous times. Perhaps the most well known is the 1950 Disney version, starring Robert Newton as Long John Silver. His eye rolling performance and exaggerated West Country accent is credited with popularising the stereotypical form of “pirate speech" that has become the pop culture default. Although an enjoyable film, it does gloss over the more sinister aspects of both the source text and history, perpetuating the myth that pirates are just loveable scoundrels. Many subsequent adaptations have fallen into the same trap to a greater or lesser degree. However, that is not the case with the 1990 version of Treasure island, which was made for the TNT cable network and released theatrically outside of the US. This darker and notably more violent adaptation closely follows the source text and is widely considered the most faithful to the book.

Ageing pirate Captain Bones, takes lodging in the Admiral Benbow inn, owned by Jim Hawkins and his widowed mother. One night, Bone’s former crew mates Black Dog and Blind Pew arrive and an altercation breaks out. As more pirates attack the inn, the local Magistrate Dr. Livesey and the local militia drive them off. Bones gives Jim the key to his chest and dies. When Jim searches the chest he finds some papers which he and Dr. Livesey then take to Squire Trelawney. He realises that one is a treasure map belonging to the notorious pirate Captain Flint. Trelawney charters the ship Hispaniola and hires Captain Smollett. He then employs a one-legged publican Long John Silver the as ships cook. Silver then convinces Trelawney to hire his friends as crew. However, both Silver and the men are former associates of Captain Flint and plan to take the treasure.

Written and directed by Fraser C. Heston Treasure Island boasts a notable cast with the likes of Christopher Lee (Blind Pew), Oliver Reed (Billy Bones), Richard Johnson (Squire Trelawney) and Julian Glover (Doctor Livesey). However the focus of this gritty adaptation is Charlton Heston as Long John Silver and Christian Bale as Jim Hawkins. Heston plays Silver as a cold, cunning and dangerous rogue, who pivots between charm and violence. Bale excels as a quick witted “Jim lad”, who is the equal of many of his seniors. The film eschews the cosy “odd couple” interpretation of prior adaptations. Both Silver and Hawkins are pragmatic in their own way and see much of themselves in each other. The production makes excellent use of locations in Devon and Cornwall in the UK, as well as Jamaica, capturing the atmosphere of the times well.

The 1950 Disney production of Treasure Island was not only instrumental in creating the modern contemporary stereotypical depiction of pirates but it also neutered the inherent violence and unpleasantness associated with such a lifestyle. That is not the case here. The crew of the Hispaniola are depicted as scurvy degenerates and it doesn’t take long for them to lapse into violence. Although not excessively graphic there are various stabbings, people being run through with cutlesses and the judicious use of the swivel gun in the final battle scene. All of which is concisely staged by veteran UK stunt co-ordinator Peter Diamond and shot by second unit director Joe Canutt. The proceedings are further bolstered by a traditional folk inspired score by Paddy Maloney and performed by his band The Chieftains. It has an appropriate nautical style without lapsing into cliche.

By following the source text closely, presenting the story within an accurate representation of the period and filling the cast with character actors of note, Treasure Island avoids the puerile and re-establishes the story as an adult, action adventure. Pirates are not jolly, fun characters as they seem to be presented in contemporary pop culture. They are thieves, murderers and worse. Director Fraser C. Heston in many ways set a benchmark as to how you effectively adapt a classic book and make it palatable for modern audiences, without denigrating the material. Sadly, few filmmakers have learned this lesson, instead often deviating from the source text and pandering to modern sensibilities. Mercifully, none of those mistakes are made here. Hence Treasure Island is highly recommended both as an entertaining film and a blue print as to how you adapt classic literature.

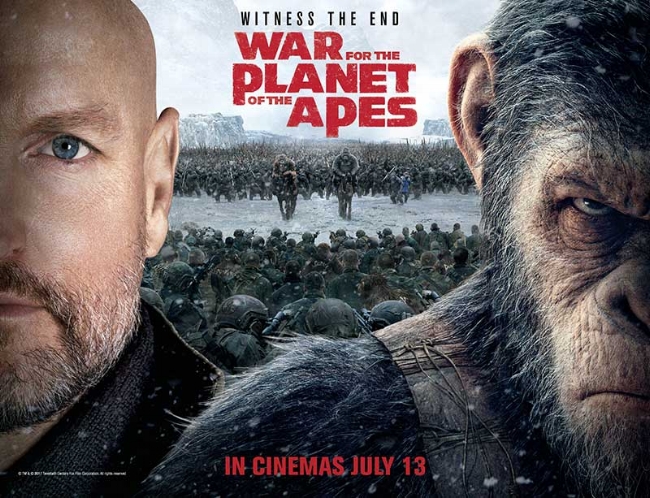

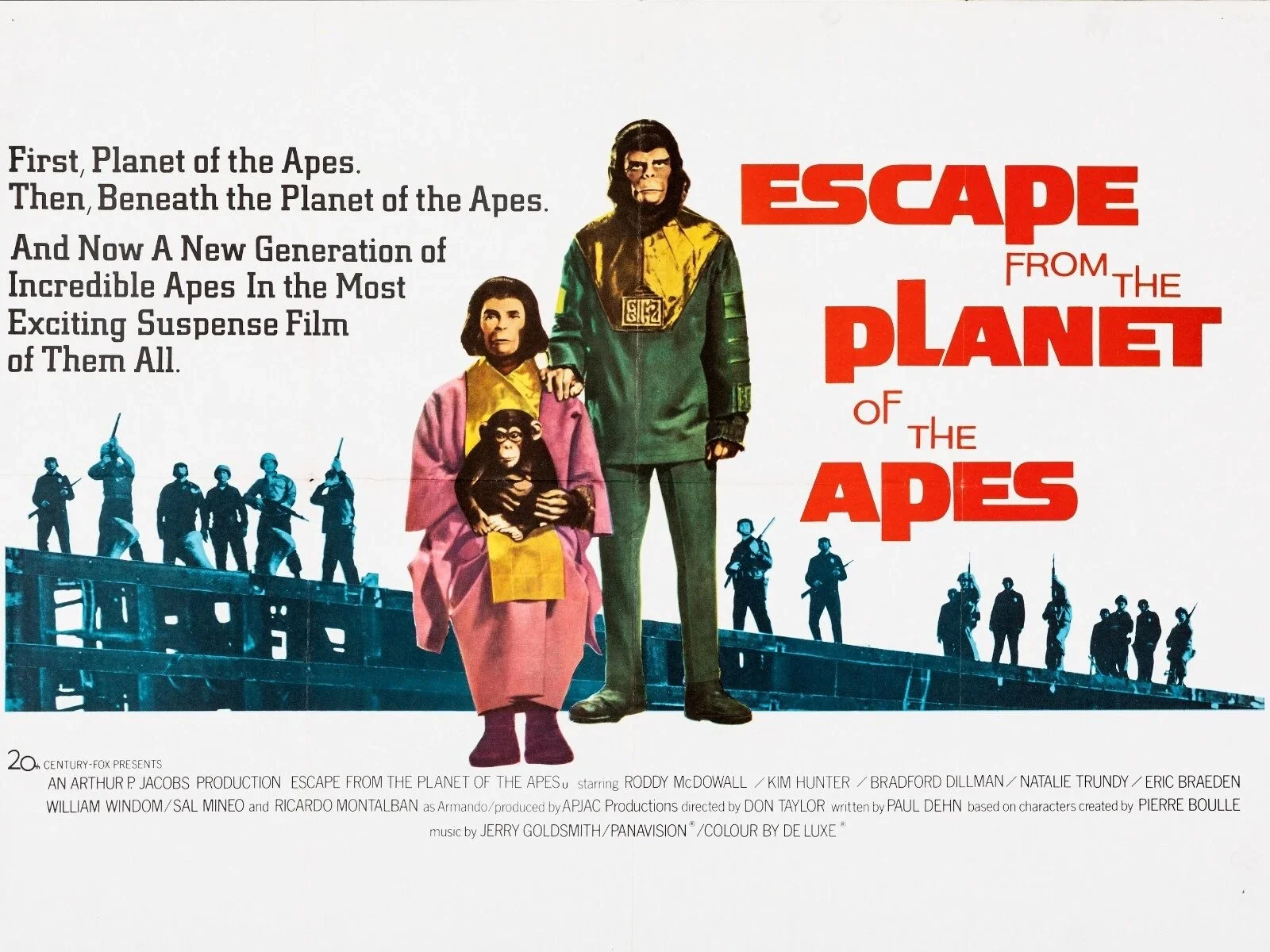

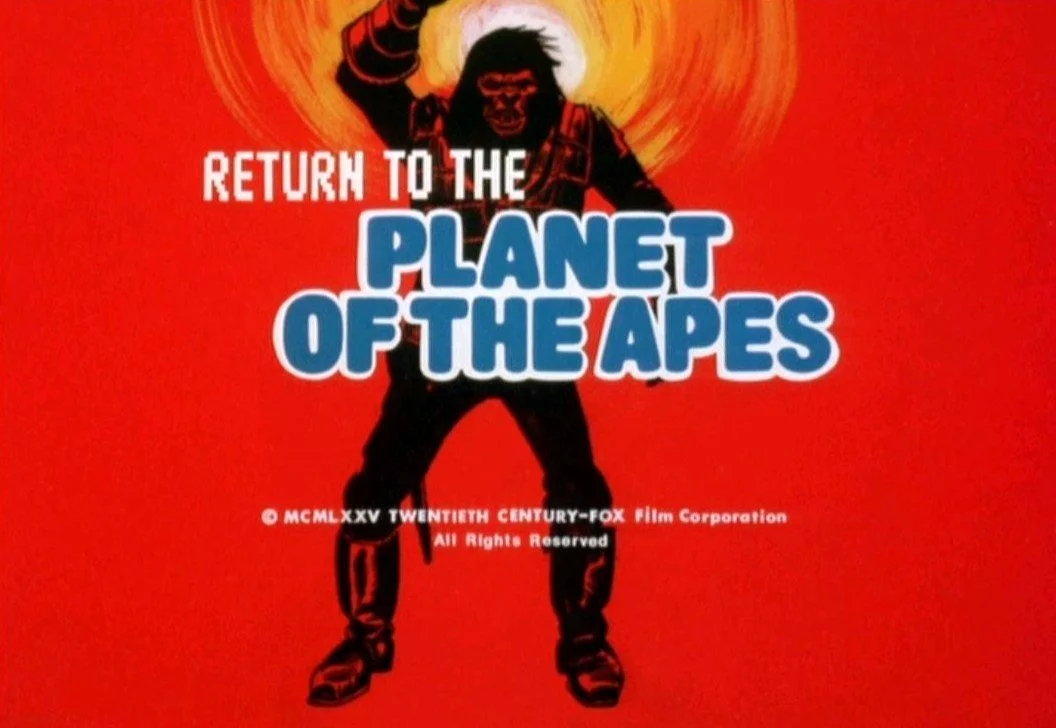

Classic Movie Themes: Escape from the Planet of the Apes

The Planet of the Apes movie franchise took a radical change of course with its third entry in the series. The first two films were set in the future and benefited from high production values to help realise a post apocalyptic earth. However, due to a substantial reduction of budget, Escape from the Planet of the Apes uses a time travel plot device to bring the ape protagonists to present day Los Angeles (1971 in this case). The result is a film with a much smaller narrative scope. However, although it lacks the science fiction spectacle of its predecessors, it features an interesting satirical exploration of celebrity culture and ponders what it is like to be deemed an enemy of the state. As ever, Roddy McDowell and Kim Hunter provide exceptional lead performances as the Chimpanzees Cornelius and Zira. Escape from the Planet of the Apes also captures the pop culture vibe of seventies America.

The Planet of the Apes movie franchise took a radical change of course with its third entry in the series. The first two films were set in the future and benefited from high production values to help realise a post apocalyptic earth. However, due to a substantial reduction of budget, Escape from the Planet of the Apes uses a time travel plot device to bring the ape protagonists to present day Los Angeles (1971 in this case). The result is a film with a much smaller narrative scope. However, although it lacks the science fiction spectacle of its predecessors, it features an interesting satirical exploration of celebrity culture and ponders what it is like to be deemed an enemy of the state. As ever, Roddy McDowell and Kim Hunter provide exceptional lead performances as the Chimpanzees Cornelius and Zira. Escape from the Planet of the Apes also captures the pop culture vibe of seventies America.

The soundtrack for Escape from the Planet of the Apes, marked the return of composer Jerry Goldsmith, whose score for Planet of the Ape had been nominated for an Oscar. On this occasion Goldsmith shifts from the stark, avant-garde style of the first film, to a lighter, more upbeat seventies sound, reflecting the film’s comedic and romantic elements. However, Goldsmith still maintains his signature use of unconventional percussion, brass, and innovative orchestral techniques. The result is a unique, fun and charming score which despite being very much of the time, does a great deal to bolster the unfolding drama. The title theme stands out with its unusual time signature and rhythmic bassline, played by the legendary session musician Carol Kaye. Goldsmith also uses both sitar and steel drums adding to the quirky character of the piece.

Despite the lighter tone of Jerry Goldsmith’s soundtrack, Escape from the Planet of the Apes is a very bleak film with respect to its ending, which features infanticide. Musically, unlike the oppressive dread of the Planet of the Ape, the score for this film embraces the musical informality of the early seventies. The cue “Shopping Spree” captures the romantic interactions between Cornelius and Zira, incorporating charming piano melodies. While tracks such as “The Hunt” offer moments of suspense and are written in a more traditional idiom. However, the main title theme for the film remains the stand out track and is presented here for your enjoyment. It remains a prime example of the inherent versatility of composer Jerry Goldsmith who on this occasion goes for a more pop infused approach to his writing. The result is a charismatic soundtrack that captures the essence of the film and the mood of the time.

Zootopia 2 AKA Zootropolis 2 (2025)

It is not unusual for Disney to change film titles when marketing them outside of the US. In 2016 they renamed the animated feature film Zootopia to Zootropolis in the UK and Europe to avoid trademark conflicts with other existing businesses. For example there is a Danish zoo which already holds the “Zootopia” name. Similarly, in Germany there is a children’s book which caused copyright conflict, which led to the film being released under the title Zoomania. Such changes, although practical for legal reasons, can sometimes cause a degree of confusion. Especially as there are numerous, low budget productions companies that go out of their way to produce similarly titled “mockbusters” whenever there are big, tentpole, releases. So for clarity, Zootopia 2 has been released in the UK as Zootropolis 2.

It is not unusual for Disney to change film titles when marketing them outside of the US. In 2016 they renamed the animated feature film Zootopia to Zootropolis in the UK and Europe to avoid trademark conflicts with other existing businesses. For example there is a Danish zoo which already holds the “Zootopia” name. Similarly, in Germany there is a children’s book which caused copyright conflict, which led to the film being released under the title Zoomania. Such changes, although practical for legal reasons, can sometimes cause a degree of confusion. Especially as there are numerous, low budget productions companies that go out of their way to produce similarly titled “mockbusters” whenever there are big, tentpole, releases. So for clarity, Zootopia 2 has been released in the UK as Zootropolis 2.

After the events of the first film, Judy Hopps (Ginnifer Goodwin) and Nick Wilde (Jason Bateman) are now officially partners at the Zootopia Police Department (ZPD). However, after an operation goes awry, due to Hopps’ over eager nature, Chief Bogo (Idris Elba) sidelines them. After finding some shed skin, Judy begins to believe there might be a snake in Zootopia. Nick is sceptical as snakes and other reptiles have been exiled from the city since an incident at its founding. Further clues lead the pair to the Zootenial Gala, celebrating the centennial anniversary of the city’s founding. It soon becomes apparent that the founding family of Lynxes have a dark secret and that a grave miscarriage of justice has been covered up for years. However, Judy and Nick are framed and are forced to go on the run.

Despite a 9 year gap between the release of the first film and this sequel, Zootropolis 2 is immediately engaging mainly due to the strength and appeal of the central characters. The jokes come thick and fast, with plenty of slapstick humour and sight gags. As ever with animated films, action scenes are very frenetic and demand your concentration to see all that is going on. The screenplay by Jared Bush contains the usual pop culture references and clever asides for adult viewers. Hence we have clever homages to The Silence of the Lambs and The Shining. The voice cast is sumptuous and sprawling, ranging from artists such as Shakira and Ed Sheeran, Alan Tudyk, John Leguizamo and Jenny Slate. Guessing the identity of a celebrity voice actor is part of the fun of the film. It took me a few minutes to identify the ever excellent Danny Trejo, as Jesús, a plumed basilisk lizard.

The story, although entertaining, is a little drawn out with several lengthy set pieces unnecessarily expanding its running time. However, this is standard operational procedure these days for films of this kind. Although not as novel as the first film, Zootropolis 2 is engaging, funny and handles sentiment very well. It is interesting how a lot of mainstream Hollywood films are currently exploring traditional themes and focusing on subtexts of equality, inclusion and social cohesion. All of which seems to fly in the face and provide a counter narrative to aspects of contemporary US politics. As for the usual bi-partisan criticism and pushback that occurs when such material is present in mainstream entertainment, it has not harmed the box office returns for Zootropolis 2. The film has earned globally $1.475 billion, having cost $150 million to make. So much for “go woke, go broke”.

The Running Man (2025)

Stephen King’s dystopian story, The Running Man, was previously adapted very loosely in 1987, as a vehicle for Arnold Schwarzenegger. That version focused mainly on the “Battle Royale” element of the story and leaned heavily into Arnie’s personality, rather than the politics of the book. It also wasn’t well received by the author. Edgar Wright’s remake follows the source text a lot more closely and is far more interested in its political themes and wider social commentary. Furthermore, this version re-establishes the everyman quality of the hero of Ben Richards, rather than him being the muscle bound, ex-military hero as per Mr. Schwarzenegger’s prior interpretation. This time round, The Running Man uses a lot of the visual and narrative tropes of contemporary reality TV, making this forty three year old story very relevant to today’s viewers and couching the film in a style that is recognisable and accessible.

Stephen King’s dystopian story, The Running Man, was previously adapted very loosely in 1987, as a vehicle for Arnold Schwarzenegger. That version focused mainly on the “Battle Royale” element of the story and leaned heavily into Arnie’s personality, rather than the politics of the book. It also wasn’t well received by the author. Edgar Wright’s remake follows the source text a lot more closely and is far more interested in its political themes and wider social commentary. Furthermore, this version re-establishes the everyman quality of the hero of Ben Richards, rather than him being the muscle bound, ex-military hero as per Mr. Schwarzenegger’s prior interpretation. This time round, The Running Man uses a lot of the visual and narrative tropes of contemporary reality TV, making this forty three year old story very relevant to today’s viewers and couching the film in a style that is recognisable and accessible.

In the near future, the United States is governed by an authoritarian media conglomerate known simply as the Network. The majority of the public exist in poverty with minimal access to healthcare, while the Network distracts the populace with low-quality, violent game shows and reality television. The most popular show is “The Running Man”, in which "runners" have the opportunity to win $1 billion by surviving a 30 day, nationwide manhunt, by the Network's five “hunters”. Provided with $1,000 and a 12-hour head start, “the runners” must document their experiences daily, or they will lose their earnings yet still remain targets for the hunt. Ben Richards (Glen Powell), a blacklisted blue collar worker, enters the show desperate to earn money to pay for his daughter’s healthcare. The TV show’s producer, Dan Killian, instantly senses that Richard’s maybe an exceptional contestant and a means to achieve the highest ratings ever.

British director Edgar Wright takes a calculated risk by not smoothing the rough edges of the central character of Ben Richards. Although he’s a man with a moral code and fierce loyalty to his family, his anger issues can diminish some of the audience’s sympathy for him. However, as it is this very quality that makes him a perfect candidate for the predatory TV shows that abound in the authoritarian state, it is a necessary evil. As ever, the director cleverly uses gallows humour, intelligent “needle drops” and clever dialogue to make his point. The action scenes are well handled and not too hyperbolic in scope. Shot in London, Glasgow and Bulgaria, the film looks refreshingly unamerican and pivots well between the grimy, run down aesthetic of the poor neighbourhoods and the neon modernism of the rich suburbs.

Glen Powell is well cast and his character has a logical arc. He also acquits himself well in the action scenes and the use of CGI is minimal. Josh Brolin is plausible as the scheming producer of this titular TV show and exudes appropriate insincere charm. Colman Domingo has a lot of fun with the role of Booby T, the slick host of the nation’s favourite show, whipping up the audience with his inflammatory and hyperbolic rhetoric. If there is a weak character then it is Evan McCone played by Lee Pace. Although the main “hunter” of the story, Pace has little to do apart until the third act when his role becomes mainly expository. However, this aside, The Running Man is a fast paced, clever and slick re-imagining of a somewhat bleak novel. It is not just another generic action movie and clearly shows the hallmark of its director’s persona and style.

The Haunted Doll’s House (2012)

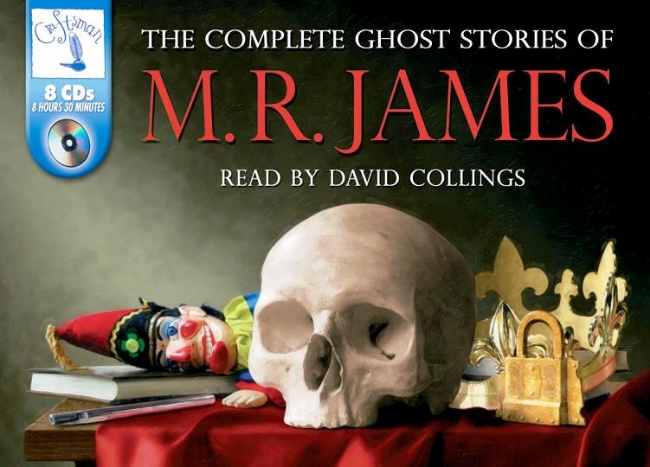

The Haunted Dolls House is a short film based on a story by M.R. James about a unique antique that is subject to supernatural phenomenon. Adapted by Stephen Gray and David Lilley, this is the third of three short films based upon James’ work that the pair have made. It stars Steven Dolton as Mr. Dillet, a collector of antique dolls houses, who acquires a bargain only to discover that it harbours a ghostly secret. Made on an extremely modest budget over the course of 2012 this clever, innovative and rather sinister adaptation is a fine example of short film creativity. It manages to offer a unique visual depiction of M.R. James’ classic story whilst capturing the unsettling quality of the author’s work. Like so many independently made short films it is clearly a labour of love, made with modest resources. It succinctly captures the spirit of the author’s work and is both innovative and rewarding.

The Haunted Doll’s House is a short film based on a story by M.R. James about a unique antique that is subject to supernatural phenomenon. Adapted by Stephen Gray and David Lilley, this is the third of three short films based upon James’ work that the pair have made. It stars Steven Dolton as Mr. Dillet, a collector of antique doll’s houses, who acquires a bargain only to discover that it harbours a ghostly secret. Made on an extremely modest budget over the course of 2012 this clever, innovative and rather sinister adaptation is a fine example of short film creativity. It manages to offer a unique visual depiction of M.R. James’ classic story whilst capturing the unsettling quality of the author’s work. Like so many independently made short films it is clearly a labour of love, made with modest resources. It succinctly captures the spirit of the author’s work and is both innovative and rewarding.

The Haunted Doll’s House creates an interesting period atmosphere of the early nineteen twenties and sets the scenes for the ghostly events. Professional antique collector Mr. Dillet seems very pleased with his latest acquisition and sits late into the night cataloguing its contents by dictating into a Phonograph Recorder. However, as Mr. Dilet lists the respective details, they seem to become more intricate each time he checks them. Perhaps he is just overly tired? He subsequently retires to bed for the evening, however he is woken during the night when a strange light illuminates the doll's house. It would appear that the latest addition to his collection has something to show him. A rather disturbing story plays out among the antique’s occupants; a family of dolls consisting of a husband and wife, two children and a bedridden Grandfather.

The director's use of stop motion animation is a major positive asset for this adaptation. The minimalist character design of the dolls and the lack of dialogue do not in any way hinder the narrative. The silent actions of the puppets not only clearly convey the story but embellish it with a great deal of atmosphere and pathos. In many ways it plays out like a sinister episode of Camberwick Green and I do not mean that in a derogatory manner but as the highest possible compliment. The transition from animation to live action is cleverly done and provides an appropriate codicil to this supernatural tale. The Haunted Doll’s House makes good use of its eleven minute running time making it an ideal seasonal ghost story. It is a fine example of the high quality independent short films that you can often find online, if you take the time to search them out. The Haunted Doll’s House is available to watch on YouTube.

No One Lives (2012)

A lot of people may know Luke Evans from the live action version of Beauty and the Beast or Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit trilogy. With his matinee idol good looks, charming Welsh demeanour and his “smoky” tenor singing voice, he projects a sense of old school stardom. Which brings us to No One Lives; a film which is a radical departure from his previous work. His performance is disconcerting to say the least and the film is somewhat unhinged. Directed by Ryuhei Kitamura, who made an interesting adaptation of Clive Barker’s The Midnight Meat Train, this cinematic outing is similarly replete with robust shocks and gore. There are some interesting ideas about the nature of violence, Stockholm Syndrome and whether one should deny or embrace one’s nature. However, these are ultimately minor asides. Philosophical musings in between bouts of surprisingly striking unpleasantness.

A lot of people may know Luke Evans from the live action version of Beauty and the Beast or Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit trilogy. With his matinee idol good looks, charming Welsh demeanour and his “smoky” tenor singing voice, he projects a sense of old school stardom. Which brings us to No One Lives; a film which is a radical departure from his previous work. His performance is disconcerting to say the least and the film is somewhat unhinged. Directed by Ryuhei Kitamura, who made an interesting adaptation of Clive Barker’s The Midnight Meat Train, this cinematic outing is similarly replete with robust shocks and gore. There are some interesting ideas about the nature of violence, Stockholm Syndrome and whether one should deny or embrace one’s nature. However, these are ultimately minor asides. Philosophical musings in between bouts of surprisingly striking unpleasantness.

After a burglary goes awry, a small town gang of robbers consider how to recoup their losses. Led by Hoag (Lee Tergesen), the gang consists of his brother Ethan (Brodus Clay), his daughter Amber (Lindsey Shaw), his girlfriend Tamara (America Olivo), Amber's boyfriend Denny (Beau Knapp) and the volatile Flynn (Derek Magyar). Flynn targets a couple passing through town, assuming that the expensive car and trailer means that they’re rich and easy pickings. The couple, Betty (Laura Ramsey) and “The Driver” (Luke Evans) are taken to an abandoned gas station by Ethan while Flynn searches their car. Betty, clearly distressed by events, commits suicide. Meanwhile Flynn discovers a woman held captive in the car trunk. She is Emma Ward (Adelaide Clemens) who was kidnapped 8 months ago. The gang quickly realise they’ve crossed paths with a predator and are in serious danger.

No One Lives quickly sets out its stall and keeps moving over an efficient 86 minutes. What is effectively a blending of the slasher and revenge genres is somewhat elevated above the average by an enigmatic performance by Luke Evans. The screenplay by David Cohen focuses on the dynamic between kidnapper and victim. Adelaide Clemens gives a good performance as a woman determined to survive and not become just a “victim”. Luke Evans’character remains suitably vague, with little back story. He often lapses into introspective musing about his own nature, much to the confusion of his “mediocre” prey. When asked if he’s a serial killer he retorts “A serial killer? Sweet Jesus, no. Serial killers deal in singularities. I’m a numbers guy”. When another victim states how they don’t deserve what is happening, he blithely agrees and commiserates that she is “just unlucky”.

Shot on 16mm film, No One Lives has a grimy aesthetic that suits the subject matter. Cinematographer Daniel Pearl was the DP on Tobe Hooper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Next to Luke Evans’ compelling presence, the second standout aspect of this film are the set pieces. Japanese Australian Director Ryuhei Kitamura constructs some singularly unpleasant death scenes and knows exactly how to fish hook horror fans. He also explores some interesting themes, for those who want something a little deeper but they are presented as optional extras. No One Lives will primarily appeal to horror aficionados due to several “squishy” WTF moments. It also works as a thriller but casual viewers may find the excess of unpleasantness a little too gruelling. The film is certainly an interesting addition to Luke Evans’ resume. I hope he does more like this.

Underwater (2020)

In the near future, Kepler 822, a research and drilling facility located at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, suffers a sudden and catastrophic structural failure. There are only six survivors. Mechanical engineer Norah Price (Kristen Stewart), Captain Lucien (Vincent Cassel), biologist Emily Haversham (Jessica Henwick), engineer Liam Smith (John Gallagher Jr.) and crew members Rodrigo (Mamoudou Athie) and Paul (T.J. Miller). As all the functional escape pods have been used and they are unable to contact the surface, the Captain suggests using pressurized suits to walk one mile across the ocean floor to the Roebuck 641 drill installation. There they will find more escape pods. However, it soon becomes apparent that the disaster was not caused by an undersea earthquake and that they are not alone as they make their journey.

In the near future, Kepler 822, a research and drilling facility located at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, suffers a sudden and catastrophic structural failure. There are only six survivors. Mechanical engineer Norah Price (Kristen Stewart), Captain Lucien (Vincent Cassel), biologist Emily Haversham (Jessica Henwick), engineer Liam Smith (John Gallagher Jr.) and crew members Rodrigo (Mamoudou Athie) and Paul (T.J. Miller). As all the functional escape pods have been used and they are unable to contact the surface, the Captain suggests using pressurized suits to walk one mile across the ocean floor to the Roebuck 641 drill installation. There they will find more escape pods. However, it soon becomes apparent that the disaster was not caused by an undersea earthquake and that they are not alone as they make their journey.

Underwater starts with all the hallmarks of a film that is very derivative of Alien. The technology and immediate environment all have an industrial aesthetic that is worn and feels used. The crew is made up of “working men” rather than clean cut academics and the corporation that owns and runs the facility is simply referenced by branding on bulkheads or on monitor lockscreens. The screenplay by Brian Duffield (No One Will Save You) and Adam Cozad is lean and moves quickly but there’s sufficient dialogue to get the measure of each character. The threat comes quickly during the film’s concise 95 minute running time and it is here that Underwater diverges from similar films. DeepStar Six featured a prehistoric Eurypterid and Leviathan had monsters caused by mutagens containing piscine DNA. Underwater has a distinctly Lovecraftian nemesis.

Director William Eubank maintains a tense and claustrophobic atmosphere. Due to the seven mile depth, there is no sunlight and the ocean floor is illuminated by the lights on the crew’s environment suits and from LEDs on equipment. Hence, for the first two acts the aquatic menace is seen only fleetingly and the shocks come mainly from jump scares. The death scenes are hectically edited and you certainly get the impression that something unpleasant has happened but you cannot see the detail. Although initially frustrating this becomes the film’s greatest strength as it becomes clear this is not just a case of an apex predator. The crew do a little theorising about what is happening around them but it is left vague and there are no convenient answers. The climax and final reveal work better as a result of this approach.

Underwater is an effective genre outing. It isn’t a masterpiece and certainly isn’t original. It takes some standard tropes from “creature features” and horror films and it tries its best to do something a little different with them. The $60 million budget covers a lot of ground, with the sets, production design and VFXs looking polished and plausible. The cast is competent and the characters likeable. Marco Beltrami’s score at times has shades of vintage John Carpenter and Alan Howarth. But it is the film’s final act that is responsible for making Underwater better than average. Casual viewers may not necessarily get the inference but those who are aware of the concept of cosmic horror should enjoy the eldritch payoff. Underwater is a well crafted rollercoaster ride, that doesn’t out stay its welcome and should be judged as such.

Primitive War (2025)

One of the most common objections raised regarding the Jurassic Park/Jurassic World franchise is that the films are specifically made to obtain a PG-13 rating from the Motion Picture Association, for purely commercial reasons. Hence, in all films, there is little on screen violence and the dinosaurs are mainly portrayed as a threat and a means of providing jump scares. When a character is killed by a dinosaur it usually happens off screen, is obscured by something else in frame, or is shown in long shot with very little detail. The realities of being eaten alive by a predator are conspicuously absent. Hence, audiences looking for films featuring more graphic dinosaur attacks, have not been well catered for apart from some minor direct-to-video titles. Primitive War finally fills this gap in the market with a frenetic genre mashup that strives to punch above is budgetary weight.

One of the most common objections raised regarding the Jurassic Park/Jurassic World franchise is that the films are specifically made to obtain a PG-13 rating from the Motion Picture Association, for purely commercial reasons. Hence, in all films, there is little on screen violence and the dinosaurs are mainly portrayed as a threat and a means of providing jump scares. When a character is killed by a dinosaur it usually happens off screen, is obscured by something else in frame, or is shown in long shot with very little detail. The realities of being eaten alive by a predator are conspicuously absent. Hence, audiences looking for films featuring more graphic dinosaur attacks, have not been well catered for apart from some minor direct-to-video titles. Primitive War finally fills this gap in the market with a frenetic genre mashup that strives to punch above is budgetary weight.

In 1968 during the Vietnam War, Colonel Jericho (Jeremy Piven) orders Vulture Squad, a reconnaissance unit, to track down a Green Beret platoon that has gone missing on a classified mission. Sergeant First Class Ryan Baker (Ryan Kwanten) is concerned about the secrecy surrounding the mission and well being of his squad. After being dropped by helicopter in a remote region of the jungle the squad finds evidence of a firefight along with a large bird-like foot print. Upon searching a tunnel complex they are attacked by a pack of Deinonychus and are split up. Baker along with new squad member Verne (Carlos Sanson) are rescued from a Tyrannosaurus attack by a Soviet paleontologist, Sofia Wagner (Tricia Helfer), who shelters them in a nearby bunker. He learns that a Russian General has been experimenting with a particle collider, resulting in wormholes and the dinosaurs’ presence.

Primitive War takes the standard genre tropes found in Vietnam War movies, along with those common to “creature features” and mixes them together with B movie aplomb and the candid honesty inherent in Australian exploitation cinema. The result is fast paced, violent and thoroughly entertaining. The computer generated dinosaurs and animatronics are broadly good and when it does start to get a bit sketchy, it’s not a deal breaker because it is clear that the production is really trying hard to do it best with what its budget. Furthermore, rather than just resting on its high concept, exploitation laurels, Primitive War even takes a stab at focusing on characters and getting audiences emotionally invested in the protagonists. You could argue that it tries a little too hard but the film is ambitious and that is a praiseworthy quality these days because so many film productions do exactly the opposite.

Based on books by Ethan Pettus, who co-wrote the screenplay with director Luke Sparke, Primitive War strikes the right tone with its hard boiled, military dialogue and hyperbolic kiss-off lines. I especially enjoyed “Come get some, you Foghorn Leghorn motherfuckers”. The cast, who are mainly from television, acquit themselves well and the screenplay endeavours to give this dirty half-dozen some back story, touching upon such themes as PTSD and survivors guilt. The set pieces are violent and the dinosaur attacks show the reality of being devoured alive. Considering the $8 million dollar budget, the visual effects hold up well. There are some sequences that don’t work as well such as an aerial attack by a flock of Quetzalcoatlus but the film strives to style it out with its pacing. The dinosaurs reflect contemporary scientific thinking, hence many are brightly coloured and feathered.

Primitive War is a superior example of exploitation filmmaking. It makes its pitch quickly and efficiently to the audience and doesn’t waste time delivering upon viewer expectations. What stands out about this production is that it doesn’t allow its financial constraints to impact upon its creative ambitions. Director Luke Sparke and the cast clearly took the film seriously and strived to do their best. The result is a film that is ambitious, entertaining and exactly what was promised in the trailer. There are some rough edges along the way but that is to be expected. This isn’t a big studio production. Perhaps it could have been a slightly tighter 110 minutes instead of 133 but there are far more bloated, self indulgent films out there. Like most of the Jurassic Park/Jurassic World franchise. Unlike a lot of mainstream films these days, Primitive War is an honest film. If you want dinosaurs versus soldiers during the Vietnam War, that is what you get.

Emperor Of The North (1973)

During the seventies, cinema was not only a source of mass, commercial entertainment but was still perceived as a medium for intellectual and philosophical discourse. Television was a poor relation in terms of art and cultural significance. Film was where the so called auteur director could muse and ruminate upon the nature of the human condition and audiences could subsequently gush sycophantically about their work at dinner parties. Or something like that. Let it suffice to say that some film makers were still indulged by studios and financiers, who were still keen to cash in on the cultural sea change that came to Hollywood in the late sixties. It’s difficult to see how a film such as Emperor of the North (AKA Emperor of the North Pole) could have been made otherwise. A film set in the Great Depression about a hobo illegally travelling on freight trains and his feud with a ruthless conductor.

During the seventies, cinema was not only a source of mass, commercial entertainment but was still perceived as a medium for intellectual and philosophical discourse. Television was a poor relation in terms of art and cultural significance. Film was where the so called auteur director could muse and ruminate upon the nature of the human condition and audiences could subsequently gush sycophantically about their work at dinner parties. Or something like that. Let it suffice to say that some film makers were still indulged by studios and financiers, who were still keen to cash in on the cultural sea change that came to Hollywood in the late sixties. It’s difficult to see how a film such as Emperor of the North (AKA Emperor of the North Pole) could have been made otherwise. A film set in the Great Depression about a hobo illegally travelling on freight trains and his feud with a ruthless conductor.

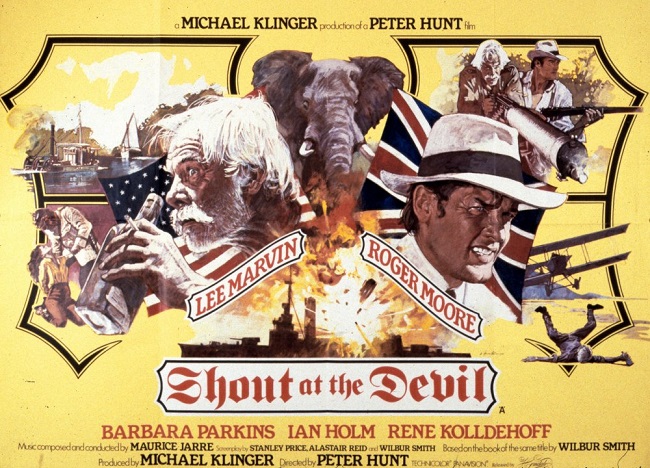

During the Great Depression, Shack (Ernest Borgnine), the conductor of the No.19 freight train on the Oregon, Pacific and Eastern Railroad, makes sure that no one rides for free on his train. When A-№1 (Lee Marvin), a legendary hobo among his peers, manages to climb aboard the train, a younger and less-experienced hobo called Cigaret (Keith Carradine) follows hims. However, he is seen by Shack, who locks them both inside the boxcar that they're hiding in. A-№1 casually sets fire to the hay onboard, forcing Shack to stop the train at a nearby rail yard. A-№1 escapes to a hobo shanty town, whereas Cigaret is caught by labourers at the rail yard. He brags to them that he is the only hobo to have ridden on Shack’s train. Shack is not liked by the labourers due to his psychotic temperament and they start taking bets that no hobo can ride Shack’s train all the way to Portland. When A-№1 hears of Cigaret’s bragging he decides to take up the challenge, thus claiming the hobo title Emperor of the North Pole.

Robert Aldrich is certainly an interesting director and I particularly like The Dirty Dozen and Flight of the Phoenix as they both examine power struggles in social hierarchies and anti-heroes battling the establishment. I also have a soft spot for Twilight’s Last Gleaming as it strives (but fails) to make a point that is still pertinent today about the nature of war. However, Emperor of the North is far too much of a niche metaphor and simply lacks sufficient narrative and character development to sustain a feature film. It frequently gets bogged down in hobo philosophy which is espoused didactically, rather than depicted directly. Furthermore, as the central characters are archetypes, we learn little of their back stories or motivations. Who was A-№1 before the financial collapse? Why is Shack so zealous in his work? No details are furnished. Director Aldrich was confident that the audience would quickly grasp his symbolism. Sadly, they didn’t or perhaps they did and just weren’t that impressed.

Emperor of the North is far from a terrible film. It is just a somewhat superficial one. It takes nearly two hours to make a minor sociopolitical point that hardly comes as a revelation. Despite having some solid set pieces, it isn’t a pure action film because of the frequent musing on hoboism and its inherent message doesn’t need to be cryptically deciphered because it is as subtle as a Rhinoceros horn up the fundament. It is essentially saved by the presence of its two lead actors who bring far more to their respective roles than what is present in the script. Lee Marvin effortlessly exudes guile and charisma as A-№1 and Ernest Borgnine is every inch the psychopath as he alternates between malevolent scowls and his signature Cheshire Cat grin. Whatever the film’s other failings, the climatic battle on a flatcar with the two stars fighting with chains and an axe, isn’t one of them.

The film’s original full title was Emperor of the North Pole, alluding to a self-deprecating hobo moniker that is grand but ultimately empty, as the North Pole at the time was considered a barren kingdom. However, outside of the US and later on home media the film title was shortened to Emperor of the North, apparently to avoid confusion that it was some sort of Christmas story. Casual viewers are probably best served not watching this one and opting for a better known example of the director’s work. Those with broader tastes may well enjoy the cast of notable character actors from the era, along with the raw brutality that is ever present in Aldrich’s work. Beware the excruciating song that plays out at the beginning of the film over a montage of steam train footage as it traverses the landscape. Tune it out if possible and reflect upon how there was once a time when a mainstream studio would greenlight a motion picture about a hobo riding trains.

Terrified (2017)

In Buenos Aires, Clara (Natalia Señorales) hears voices emanating from the plughole in her kitchen sink. The voices seem to be plotting against her. Her husband Juan (Agustín Rittano) says the sounds are coming from next door. That night, Juan finds Clara’s dead body levitating in their bathroom, slamming against the wall by an invisible force. Meanwhile their neighbour, Walter (Demián Salomón), is experiencing supernatural occurrences while he tries to sleep. An invisible force repeatedly shakes his bed. After using a video camera to film these events, he sees a tall, cadaverous figure emerging from under the bed, standing over him as he sleeps. Across the road, Alicia (Julieta Vallina) is grieving for her recently deceased son, who was run over outside Walter’s house. Alicia's ex-boyfriend, police commissioner Funes (Maximiliano Ghione) calls Jano (Norberto Gonzalo), a paranormal investigator and the pair soon discover more supernatural occurrences in the area.

In Buenos Aires, Clara (Natalia Señorales) hears voices emanating from the plughole in her kitchen sink. The voices seem to be plotting against her. Her husband Juan (Agustín Rittano) says the sounds are coming from next door. That night, Juan finds Clara’s dead body levitating in their bathroom, slamming against the wall by an invisible force. Meanwhile their neighbour, Walter (Demián Salomón), is experiencing supernatural occurrences while he tries to sleep. An invisible force repeatedly shakes his bed. After using a video camera to film these events, he sees a tall, cadaverous figure emerging from under the bed, standing over him as he sleeps. Across the road, Alicia (Julieta Vallina) is grieving for her recently deceased son, who was run over outside Walter’s house. Alicia's ex-boyfriend, police commissioner Funes (Maximiliano Ghione) calls Jano (Norberto Gonzalo), a paranormal investigator and the pair soon discover more supernatural occurrences in the area.

There are times when it benefits a film to clearly define the parameters of its story and then get on with the job of telling it efficiently. Conversely, there are other times when the best thing a film can do is simply drop the audience into the middle of some unusual event or situation and just let them experience what is happening without an excess of exposition or lore. This is what Terrified (AKA Aterrados) does. The film begins with two separate supernatural events which are quite different in nature. The story then moves on to a third vignette and it becomes apparent that these activities are happening in the same neighbourhood. Although the story subsequently follows three paranormal investigators and a local police commissioner’s attempts to determine exactly what is happening, there is no overall explanation for these events or what can be done about them.

Through the use of “hyperlink cinema”, we see several aspects of something potentially much larger unfolding. This adds much to the film’s atmosphere. Director Demián Rugna, eschews the standard approach of modern US horror of building to an event and instead dives immediately into multiple fatal, supernatural events. He further wrong foots audiences by having these activities taking place in modern suburbia, making a contemporary kitchen and bedroom the centre of these phenomena. However, he still taps into deeply ingrained, traditional fears such as something lurking under the bed. The jump scares are well conceived, as are some of the more graphic set pieces, blending CGI and practical effects cleverly. He also does not squander the film’s running time, starting at a pace and maintaining it through the lean and efficient 87 minute duration.

Another factor that makes Terrified interesting is its setting. Buenos Aires, in Argentina, is like any other modern city but it has a subtropical climate and flora. The actors also speak a specific Spanish dialect. All of which offers viewers both a degree of familiarity and a sense of difference. The ubiquitous nature of US film making along with its standard tropes can at times be a source of cinematic fatigue. Terrified side steps these, offering a well constructed and intriguing tale, with a palpable sense of tension and fear. The film excels at scaring the audience by presenting paranormal encounters in a setting one doesn’t expect by default. Furthermore, the subsequent investigations are conducted with the modern tools, which still fail to yield any viable answers. Rather than giving us an explanation, the audience is instead given an intense experience, that they then have to process themselves.

If you like to be spoon-fed highly predictable jump scares, via a story working within an established narrative framework, you may not necessarily enjoy Terrified. It doesn’t play but such cinematic rules. If you are seeking an innovative horror vehicle whose primary goal is to scare and discombobulate you, then turn off the lights, crank up the sound and revel in Demián Rugna sensory assault. Horror is an extremely flexible genre that can accommodate a broad spectrum of themes, ideas and stylistic presentations. All too often film makers simply follow an established formula, providing no more than minimal variations on a theme. Terrified does more than that, offering a window into startling and disturbing supernatural happenings. It is a film that focuses on the journey, rather than the destination and it is an exceptionally well conceived and shocking journey.

Black Sabbath (1963)

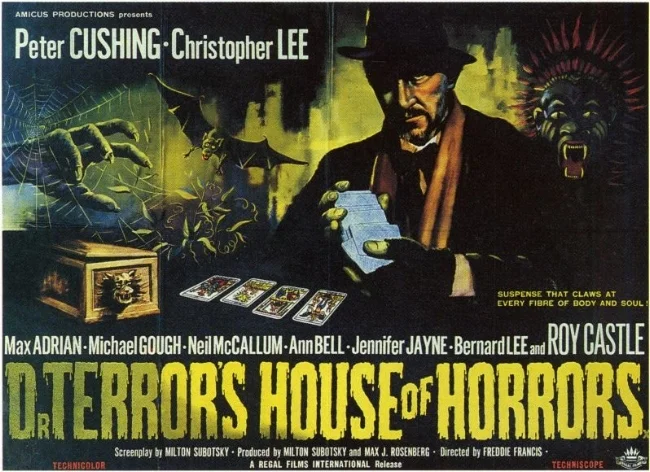

Black Sabbath (AKA I tre volti della paura) is a 1963 horror anthology film directed by Mario Bava. Although an Italian production, the film was co-financed by American International Pictures and as such was conceived to appeal to US audiences. Hence, the English dialogue edit of the film which was released in America differs significantly to the original Italian version. Despite the presence of the legendary Boris Karloff and the popularity of both anthology and gothic horror at the time,the film was only a modest success at the US box office and did not do well in Italy. However, in more recent years there has been a critical reappraisal of Black Sabbath, especially the Italian dialogue version. Many aspects of the film which are standard genre tropes today, were in fact novel at the time. Also despite the production mainly being studio bound, the film oozes style and has a striking visual aesthetic.

Black Sabbath (AKA I tre volti della paura) is a 1963 horror anthology film directed by Mario Bava. Although an Italian production, the film was co-financed by American International Pictures and as such was conceived to appeal to US audiences. Hence, the English dialogue edit of the film which was released in America differs significantly to the original Italian version. Despite the presence of the legendary Boris Karloff and the popularity of both anthology and gothic horror at the time,the film was only a modest success at the US box office and did not do well in Italy. However, in more recent years there has been a critical reappraisal of Black Sabbath, especially the Italian dialogue version. Many aspects of the film which are standard genre tropes today, were in fact novel at the time. Also despite the production mainly being studio bound, the film oozes style and has a striking visual aesthetic.

The Italian version starts with “The Telephone”, in which upmarket call-girl Rosy (Michèle Mercier) returns to her basement apartment at night and starts to receive a series of menacing phone calls, allegedly from her former pimp Frank who she testified against and had jailed. She calls an ex-lover, Mary (Lidia Alfonsi), and asks for her help but things are not as they appear to be. The second story, “The Wurdulak”, features a 19th century Serbian nobleman Vladimir D'Urfe (Mark Damon) who takes shelter for the night with a peasant family in their farmhouse. They await the return of their father Gorca (Boris Karloff) who has gone to kill a Turkish bandit who has been terrorising the area. When Gorca returns his family fear that he has become a Wurdulak; a living corpse that feeds on blood. The final story “The Drop of Water”, is set in 1910 London, features her nurse Helen Chester (Jacqueline Pierreux) who steals a sapphire ring from an elderly deceased medium she is preparing for burial. On returning home she is plagued by the sound of dripping water and a ghostly apparition.

The most immediate difference between the US and Italian versions of Black Sabbath is the colour timings. The Italian print which was processed by Technicolor Roma and supervised by Mario Bava, has a vibrant, more flamboyantly nightmarish colour palette. The cinematography by Ubaldo Terzano and Mario Bava is fluid and often uses movement to create atmosphere. The use of vivid, saturated hues and dramatic lighting, particularly the contrast between light and shadow, creates a foreboding and menacing atmosphere, making the visuals themselves participants in the horror. Karloff’s entrance as Gorca is a masterfully composed sequence. He steps into frame with his back to the camera and the limps ominously towards the farmhouse. His imposing demeanour is enhanced by makeup that contrasts with being lit from below. These details are more pronounced in this version.

The Italian edit also has the stories in a different order to the US release. The film begins with “The Telephone” and in this version the sexual subtext is far more apparent. Rosy is clearly a prostitute. Mary is possibly a former client who subsequently fell in love with Rosy. Themes that were excised from the US prints. This story plays out in many respects as a giallo, bearing many narrative hallmarks. Next is “The Wurdulak”, the most gothic of the three vignettes. The Italian version has a little more violence, when Gorca reveals the head of the dead bandit. Finally “The Drop of Water” is identical in both versions of the film, as its shock lies in jump scares, rather than violence. The US release has a different introduction by Boris Karloff and he links each new story. The Italian version has him appear at the start and end of the film only. The original score by Roberto Nicolosi is present in the Italian release but was replaced in the US version by a new soundtrack by AIP stalwart Les Baxter.

Overall the Italian release of Black Sabbath, is the superior version. It delivers three supernatural tales, featuring adult themes with style and atmosphere. The US version is tamer in tone, mainly because horror films at the time were aimed at the teenage market. The visual impact of the Italian version is greater due to the more vivid use of colour and the original score is less intrusive and melodramatic than the new American soundtrack. If Mario Bava’s version has one failing it is the dubbing of Boris Karloff into Italian. Although a necessity for the film’s release in its home market, it does have an impact upon Karloff’s performance. Modern audiences may consider some of the ideas, especially those in “The Telephone”, to be a little tired and overused However, the notion of a stalker in this instance predates most US films by a decade.

The artistry and structure in Black Sabbath, particularly its blend of suspense and supernatural horror, directly influenced the Italian giallo genre and the wider global horror aesthetic. Beyond the supernatural, the film masterfully explores themes of guilt and the encroaching forces of evil, making the terror deeply relatable and psychologically disturbing. Mario Bava continued to have a significant impact upon cinema throughout the sixties and seventies. He pre-empted the US slasher genre with the gory giallo A Bay of Blood (1971) and clearly had an influence upon Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) with his atmospheric science fiction film, Planet of the Vampires (1965). Black Sabbath is a fine example of the stylish European approach to gothic horror and is therefore “must see” viewing for horror aficionados. Seek out the Italian version if possible.

Biggles (1986)

After the success of Raiders of the Lost Ark in 1981, filmmakers scrambled to find existing intellectual properties that they could use for similar films. Hence archaic heroes such as Alan Quatermain were hastily given a modern makeover and thrust into generic movies, in a vague attempt to replicate Steven Spielberg’s successful formula. Which brings us neatly on to James Charles Bigglesworth AKA “Biggles”, a fictional pilot and adventurer from a series of books written by W. E. Johns between 1932 and 1968. Several attempts had been made in the past to bring this character to the silver screen, including one by Disney but they all failed. However, the commercial and critical success of Indiana Jones provided sufficient impetus to greenlight a new film. However, due to some curious production choices, when Biggles was finally released it was far from just a period set, action movie.

After the success of Raiders of the Lost Ark in 1981, filmmakers scrambled to find existing intellectual properties that they could use for similar films. Hence archaic heroes such as Alan Quatermain were hastily given a modern makeover and thrust into generic movies, in a vague attempt to replicate Steven Spielberg’s successful formula. Which brings us neatly on to James Charles Bigglesworth AKA “Biggles”, a fictional pilot and adventurer from a series of books written by W. E. Johns between 1932 and 1968. Several attempts had been made in the past to bring this character to the silver screen, including one by Disney but they all failed. However, the commercial and critical success of Indiana Jones provided sufficient impetus to greenlight a new film. However, due to some curious production choices, when Biggles was finally released it was far from just a period set, action movie.

Catering salesman Jim Ferguson (Alex Hyde-White), is unexpectedly transported from New York City to 1917 France, where he saves the life of Royal Flying Corps pilot James "Biggles" Bigglesworth (Neil Dickson) after he is shot down on a reconnaissance mission. Immediately afterwards, Jim is transported back to 1986, where his fiance Debbie (Fiona Hutchinson) struggles to believe his explanation as to what happened to him. However, Jim is subsequently visited by Biggles’ former commanding officer, Air Commodore William Raymond. Raymond tells him about his theory that Ferguson and Biggles are "time twins", spontaneously transported through time when the other is in mortal danger. Shortly after Jim is reunited with Biggles, along with Debbie who held onto Jim when he was transported across time. They discover that the Germans are working on a sonic weapon that could change the outcome of The Great War.

Yellowbill Productions acquired the rights to the Biggles books in 1981 and the initial aspirations of producer Kent Walwin were high. The plan was to produce a series of period set films, in the James Bond idiom, featuring action and drama. Both Jeremy Irons and Oliver Reed were originally associated with the production. Initial drafts of the screenplay were set in WWI and were faithful to W. E. Johns’ original novels. However, the producers subsequently decided to add a science fiction spin to the main story, possibly due to the imminent release of Back to the Future. Whatever the reason, the film morphed into a curious hybrid which didn’t really do justice to either the science fiction or period action genres. Furthermore, the production schedule was expedited so it could take advantage of UK tax breaks that were due to expire. As a result the screenplay was still being rewritten when director John Hough began filming.

As a result, Biggles (retitled Biggles: Adventures in Time in the US) is somewhat narratively and tonally inconsistent. Neil Dickson is well cast as James Charles Bigglesworth but has to compete for screen time with Jim Ferguson, his somewhat uninteresting time twin. The film briefly improves when Peter Cushing appears, in what was to be this iconic actor’s last role. But overall Biggles just doesn’t know what it wants to be. It feels like the writers have added multiple cinematic tropes to the screenplay out of desperation. Sadly, the romance and occasional slapstick humour fall flat. The action scenes, although well conceived, betray their low budget, featuring old tricks such as a plane flying behind a hill before exploding. Plus there’s a somewhat gory scene involving a soldier who is killed by the sonic weapon, which seems out of place.

Biggles failed at the UK box office and was equally unsuccessful when released later in the US. However, all things considered, a flawed film can still be an entertaining one. Biggles is all over the place but it does raise a wry smile from time to time. There’s plenty of the old “British stiff upper lip” with our hero telling his nemesis, Hauptmann Erich von Stalhein (Marcus Gilbert) “I'll not put a bullet in your head, old boy, because that’s not how we do business”. The flying scenes have a sense of momentum and are well shot by second unit director Terry Coles, who had done similar work on Battle of Britain. The soundtrack is also peppered with several very eighties songs from Mötley Crüe, Queen and Jon Anderson from Yes. Hence, if you’re looking for some undemanding entertainment or have an interest in the various films that tried to cash in on Indiana Jones, then you may wish to give Biggles a go.

Red Dawn (2012)

Setting aside the hubris of remaking a film such as Red Dawn, the 2012 reboot had a troubled production. Shot over the course of late 2009, on location in Michigan, MGM intended to release the film in September 2010. However, the studio’s financial problems became unsustainable over the course of that year and the film was shelved, while a financial solution was sought. Furthermore, while Red Dawn was in post production, there was a major economic shift within Hollywood due to the increasing importance of the Chinese market. This was a significant problem for MGM because the new version of Red Dawn had the Chinese invading the USA instead of Russia. Hence there were reshoots and the need for additional visual effects, so that the Chinese could be replaced with North Koreans. MGM eventually went bankrupt and the distribution rights to Red Dawn were sold off. The film was eventually released in 2012.

Setting aside the hubris of remaking a film such as Red Dawn, the 2012 reboot had a troubled production. Shot over the course of late 2009, on location in Michigan, MGM intended to release the film in September 2010. However, the studio’s financial problems became unsustainable over the course of that year and the film was shelved, while a financial solution was sought. Furthermore, while Red Dawn was in post production, there was a major economic shift within Hollywood due to the increasing importance of the Chinese market. This was a significant problem for MGM because the new version of Red Dawn had the Chinese invading the USA instead of Russia. Hence there were reshoots and the need for additional visual effects, so that the Chinese could be replaced with North Koreans. MGM eventually went bankrupt and the distribution rights to Red Dawn were sold off. The film was eventually released in 2012.

Directed by stunt coordinator and second unit director Dan Bradley, Red Dawn offers nothing more than a formulaic narrative and a simplistic plot, supplemented by some distinctly PG-13 rated action scenes. Unlike the original film, written and directed by legendary filmmaker John Milius, there is little character development, a conspicuous lack of political commentary and nothing of note to say on the nature of war. Furthermore there is no credible attempt to explain how the US was invaded by North Korea. It is casually brushed aside after a vague opening montage and then conspicuously ignored for the remainder of the story. It is possible that such material may well have existed in the original cut of the film, when the enemy was China and there was no time or resources to replace it. Or it could just be poor writing.

Upon its release in 1984, the original version of Red Dawn was denounced as Reaganite propaganda by some critics. However, irrespective of director John Milius’ politics, the film had quite a powerful anti-war commentary. It also had characters you cared about with a credible story arc. You got to watch them grow up and make hard decisions. There was some depth to the proceedings, as well as things going “boom”. Dan Bradley’s remake has nothing other than things going “boom” and even that is not especially well done. The teenage cast lack a credible journey, simply morphing from green kids to crack troops, courtesy of a training montage. The main antagonist, Captain Cho (Will Yun Lee) lacks any backstory and is simply flagged as “bad” when he executes a lead character’s father. Calling Red Dawn perfunctory is generous.

Even the presence of Chris Hemsworth fails to improve the situation. Furthermore, this time round his character has prior military experience which mitigates the main theme of the story that wars are often fought by the young, who have to learn on their feet. The much revised script by Carl Ellsworth and Jeremy Passmore makes a few vague attempts to try and say something meaningful but these fail. Hence one character espouses “I miss Call of Duty” only for his colleague to admonish him with the philosophical retort “Dude, we're living Call of Duty... It sucks”. Viewers can’t even take solace in a gritty action scene, as the film is meticulously edited to meet the criteria of its chosen rating. The fire-fights are bloodless and there’s a single and rather obvious use of the word “Fuck” in a contrived kiss off line. Even the film’s title no longer makes any sense due to the plot changes.

Electra Glide in Blue (1973)

American music producer James William Guercio is primarily known for his work in the music industry. He was the producer of the band Chicago’s first eleven studio albums. In the mid-seventies he also managed the Beach Boys and was a member of their backing band. He was during this time, well known in his field and respected. In 1973, Guercio directed, produced and wrote the score for his first and only feature film, Electra Glide in Blue. He was 28 years old at the time. Upon release the film received mixed reviews from many traditional US newspapers, who were dismissive of its revisionist themes and poetical style. However, in Europe the film was received more favourably and was entered into the 1973 Cannes Film Festival. Fifty two years on and Electra Glide in Blue is now considered an overlooked cult classic and is analysed in a more measured fashion.

American music producer James William Guercio is primarily known for his work in the music industry. He was the producer of the band Chicago’s first eleven studio albums. In the mid-seventies he also managed the Beach Boys and was a member of their backing band. He was during this time, well known in his field and respected. In 1973, Guercio directed, produced and wrote the score for his first and only feature film, Electra Glide in Blue. He was 28 years old at the time. Upon release the film received mixed reviews from many traditional US newspapers, who were dismissive of its revisionist themes and poetical style. However, in Europe the film was received more favourably and was entered into the 1973 Cannes Film Festival. Fifty two years on and Electra Glide in Blue is now considered an overlooked cult classic and is analysed in a more measured fashion.

John Wintergreen (Robert Blake) is a short motorcycle cop who patrols the rural Arizona highways with his partner Zipper (Billy "Green" Bush). Wintergreen is involved in a passionate affair with local bar owner Jolene (Jeannine Riley) and aspires to transfer to the Homicide unit. When he is informed by Crazy Willie (Elisha Cooke Jnr) of an apparent suicide-by-shotgun, Wintergreen believes the case is actually a murder. Detective Harve Poole (Mitchell Ryan) confirms the case as a homicide, after a .22 bullet during the autopsy, as well as learning about a possible missing $5,000 from the victim's home. Wintergreen is subsequently transferred to homicide to assist Poole. He soon finds himself at odds with both the detective’s methods and the local hippie community. Matters are further complicated when he learns that Jolene has an existing relationship with Poole.

Apparently Guercio watched the films of John Ford numerous times as a child. Hence when facing the prospect of filming in Monument Valley, Arizona, Guercio sought out a suitably talented Director of Photography who could capture the visual impact of the environment. He allegedly took a director’s fee of one dollar, so that the production had sufficient budget to hire Conrad Hall (Cool Hand Luke, Hell in the Pacific and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) as cinematographer. Hence, Electra Glide in Blue certainly has the look of a western. Yet tonally it takes elements from multiple film genres such as road movies, circular tales and black comedies. The film transcends its police procedural trappings but doesn’t quite adopt the revisionist approach to the cop genre, as seen in films such as The New Centurions. Instead it has a leisurely and poetic structure, choosing to take time with off beat character studies and aspects of the ongoing counterculture, over moving the plot forward.

Robert Blake is perfectly cast as “Big” John Wintergreen, an idealistic, easygoing and fundamentally decent motorcycle cop. An ex-marine and Vietnam veteran, he aspires to be a detective and “get paid for thinking, instead of sitting on my ass getting calluses”. Yet the enormity of the Arizona landscape and its remote nature, has created a community that is indolent, disillusioned and corrupt. The local hippy commune and culture is in many ways a protest against the status quo and both groups are contemptuous of the other. John is a tragic hero who is doomed because he is an authority figure, irrespective of his amiable personality and liberal leanings. He is also a fish out of water with his police colleagues due to his ambitions and his unwillingness to abuse his power. Hence, there is a feeling of impending doom throughout the film, though not as overt as say Lonely Are the Brave.

Electra Glide in Blue languidly sets up its central narrative, briefly touching on police procedure but overall preferring to showcase various vignettes to paint a picture of the lead characters and their motivations. Wintergreen’s height is frequently explored via some witty dialogue and his friendship with Zipper is shown to be one of polar opposites. Zipper has no ambition and seems to harbour a grudge which manifests itself in the way he bullies the local hippies. When an action scenes and chase sequence are required by the plot they are dutifully supplied. A high speed motorcycle chase between the two cops and a gang of bikers is simply conceived, well executed and practically presented. It stands out in contrast as to what has gone before in the film. The film’s soundtrack and selection of “needle drops” are also well chosen and work very well. Hardly a surprise given the director’s credentials. There is also some concert footage integrated into the plot which again highlights the cultural divide that is central to the plot.

It is not unusual for people from one creative industry to experiment with another. There is a long history of musicians crossing over to acting or film productions. Look no further than Frank Sinatra, David Bowie, Mick Jagger and George Harrison. Hence James William Guercio foray into filmmaking shouldn’t not be considered a surprise. However, the way that so many elements come together so well on his first and only film, certainly is. As to why he chose not to continue directing, is ultimately only known to Mr Guercio. After making Electra Glide in Blue, he transitioned over the next decade from music to the cattle, oil industries and other business ventures. This one time dalliance into filmmaking adds a further mystique to Electra Glide in Blue. A film very much of its time with its loose structure, tangential dialogue and bleak ending. Yet it is those very qualities and others that make it so interesting.

Gangster Squad (2013)

When I first saw the promotional trailer for Gangster Squad back in 2012, prior to its release, I wasn't especially impressed. I simply thought the film was another attempt to re-invent the gangster genre for a generation who were not especially familiar with it. I wasn't exactly overwhelmed with director Ruben Fleischer's resume either. I didn't particularly like Zombieland and haven't seen 30 Minutes Or Less. Then came the tragic mass shootings in Aurora, Colorado which led to the movie being delayed so that the original ending, which featured a shoot-out in a movie theatre, could be replaced. Hence when I finally watched this film recently, I wasn't expecting a movie up to the standards of say Once Upon A Time In America or Miller’s Crossing and it would seem that I was right do so. Gangster Squad is not especially noteworthy in any respect.

When I first saw the promotional trailer for Gangster Squad back in 2012, prior to its release, I wasn't especially impressed. I simply thought the film was another attempt to re-invent the gangster genre for a generation who were not especially familiar with it. I wasn't exactly overwhelmed with director Ruben Fleischer's resume either. I didn't particularly like Zombieland and haven't seen 30 Minutes Or Less. Then came the tragic mass shootings in Aurora, Colorado which led to the movie being delayed so that the original ending, which featured a shoot-out in a movie theatre, could be replaced. Hence when I finally watched this film recently, I wasn't expecting a movie up to the standards of say Once Upon A Time In America or Miller’s Crossing and it would seem that I was right do so. Gangster Squad is not especially noteworthy in any respect.

Set in 1949 Los Angeles, sadistic gangster Mickey Cohen (Sean Penn) expands his operations with the intention of controlling all criminal activity in the city. He has bribed sufficient officials and police, that no one is willing to cross him or testify against him. Everyone except Sergeant John O'Mara (Josh Brolin), a former World War II soldier, who wants to raise a family in a peaceful Los Angeles. Police Chief William Parker (Nick Nolte) decides to form a special unit to tackle Mickey Cohen, putting O'Mara in charge. O'Mara asks fellow cop and war veteran Jerry Wooters (Ryan Gosling) to join him. He initially refuses but reconsiders after he witnesses the murder of a young boy by Cohen's people. Despite initial setbacks, such as a casino raid thwarted by corrupt Burbank cops, the squad successfully starts to shut down key parts of Cohen’s operations, leading to violent reprisals.

Gangster Squad has a beautiful production design and a great amount of period detail lavished upon it. Unfortunately no such attention has been lavished upon the plot with Will Beall's screenplay playing like an over simplified version of The Untouchables. The movie attempts to bolster the ailing narrative with numerous action set pieces but these violent punctuation points lack any impact and are simply present out of necessity. The plot has none of the usual subtexts about poverty, honour among thieves, political or religious oppression that you usually find in this genre. Instead it’s all somewhat perfunctory. Gangster Squad suffers from all the usual problems of contemporary action films and thrillers. It looks great but rings hollow. The sort of film that you struggle to remember any specific detail a year later.

Sean Penn’s excessive performance as crime boss Cohen is trying and Emma Stone is miscast as a femme-fatale. The remainder of the cast, both old and young, struggle to bring any conviction to the uninspired dialogue. It is a criminal waste of such talents as Josh Brolin, Giovanni Ribisi and Nick Nolte. The movie’s hastily reshot conclusion is perfunctory, offering the spectacle of violence and precious little else. I was not overly concerned about the resulting plot holes arising from the rewrite, as I had precious little interest in the story or characters by this point. The overall impression I was left with after watching Gangster Squad, was that the entire production was a missed opportunity. It seems that everyone concerned with the film had obviously watched all the classics from the genre, but had sadly learned nothing from them.

Fluke (1995)

Fluke is a curious film about a man who is reincarnated as a dog and his subsequent realisation that he may have been murdered. It takes an adult novel by British author James Herbert, which is filled with philosophical musing and strives to adapt it in a far more family friendly fashion. The result is a somewhat bipolar production which thematically alternates between existential introspection and Buddhism. It then strives to deliver its message in a Disneyesque idiom. Children will potentially be confused and upset by what they see and adults will be wrongfooted by the continual shift in tone. Fluke was not a critical or commercial success upon release and the flaws that were identified by critics at the time still ring true today. That being said, Fluke is still an interesting and entertaining film, despite its faults.