Emperor Of The North (1973)

During the seventies, cinema was not only a source of mass, commercial entertainment but was still perceived as a medium for intellectual and philosophical discourse. Television was a poor relation in terms of art and cultural significance. Film was where the so called auteur director could muse and ruminate upon the nature of the human condition and audiences could subsequently gush sycophantically about their work at dinner parties. Or something like that. Let it suffice to say that some film makers were still indulged by studios and financiers, who were still keen to cash in on the cultural sea change that came to Hollywood in the late sixties. It’s difficult to see how a film such as Emperor of the North (AKA Emperor of the North Pole) could have been made otherwise. A film set in the Great Depression about a hobo illegally travelling on freight trains and his feud with a ruthless conductor.

During the seventies, cinema was not only a source of mass, commercial entertainment but was still perceived as a medium for intellectual and philosophical discourse. Television was a poor relation in terms of art and cultural significance. Film was where the so called auteur director could muse and ruminate upon the nature of the human condition and audiences could subsequently gush sycophantically about their work at dinner parties. Or something like that. Let it suffice to say that some film makers were still indulged by studios and financiers, who were still keen to cash in on the cultural sea change that came to Hollywood in the late sixties. It’s difficult to see how a film such as Emperor of the North (AKA Emperor of the North Pole) could have been made otherwise. A film set in the Great Depression about a hobo illegally travelling on freight trains and his feud with a ruthless conductor.

During the Great Depression, Shack (Ernest Borgnine), the conductor of the No.19 freight train on the Oregon, Pacific and Eastern Railroad, makes sure that no one rides for free on his train. When A-№1 (Lee Marvin), a legendary hobo among his peers, manages to climb aboard the train, a younger and less-experienced hobo called Cigaret (Keith Carradine) follows hims. However, he is seen by Shack, who locks them both inside the boxcar that they're hiding in. A-№1 casually sets fire to the hay onboard, forcing Shack to stop the train at a nearby rail yard. A-№1 escapes to a hobo shanty town, whereas Cigaret is caught by labourers at the rail yard. He brags to them that he is the only hobo to have ridden on Shack’s train. Shack is not liked by the labourers due to his psychotic temperament and they start taking bets that no hobo can ride Shack’s train all the way to Portland. When A-№1 hears of Cigaret’s bragging he decides to take up the challenge, thus claiming the hobo title Emperor of the North Pole.

Robert Aldrich is certainly an interesting director and I particularly like The Dirty Dozen and Flight of the Phoenix as they both examine power struggles in social hierarchies and anti-heroes battling the establishment. I also have a soft spot for Twilight’s Last Gleaming as it strives (but fails) to make a point that is still pertinent today about the nature of war. However, Emperor of the North is far too much of a niche metaphor and simply lacks sufficient narrative and character development to sustain a feature film. It frequently gets bogged down in hobo philosophy which is espoused didactically, rather than depicted directly. Furthermore, as the central characters are archetypes, we learn little of their back stories or motivations. Who was A-№1 before the financial collapse? Why is Shack so zealous in his work? No details are furnished. Director Aldrich was confident that the audience would quickly grasp his symbolism. Sadly, they didn’t or perhaps they did and just weren’t that impressed.

Emperor of the North is far from a terrible film. It is just a somewhat superficial one. It takes nearly two hours to make a minor sociopolitical point that hardly comes as a revelation. Despite having some solid set pieces, it isn’t a pure action film because of the frequent musing on hoboism and its inherent message doesn’t need to be cryptically deciphered because it is as subtle as a Rhinoceros horn up the fundament. It is essentially saved by the presence of its two lead actors who bring far more to their respective roles than what is present in the script. Lee Marvin effortlessly exudes guile and charisma as A-№1 and Ernest Borgnine is every inch the psychopath as he alternates between malevolent scowls and his signature Cheshire Cat grin. Whatever the film’s other failings, the climatic battle on a flatcar with the two stars fighting with chains and an axe, isn’t one of them.

The film’s original full title was Emperor of the North Pole, alluding to a self-deprecating hobo moniker that is grand but ultimately empty, as the North Pole at the time was considered a barren kingdom. However, outside of the US and later on home media the film title was shortened to Emperor of the North, apparently to avoid confusion that it was some sort of Christmas story. Casual viewers are probably best served not watching this one and opting for a better known example of the director’s work. Those with broader tastes may well enjoy the cast of notable character actors from the era, along with the raw brutality that is ever present in Aldrich’s work. Beware the excruciating song that plays out at the beginning of the film over a montage of steam train footage as it traverses the landscape. Tune it out if possible and reflect upon how there was once a time when a mainstream studio would greenlight a motion picture about a hobo riding trains.

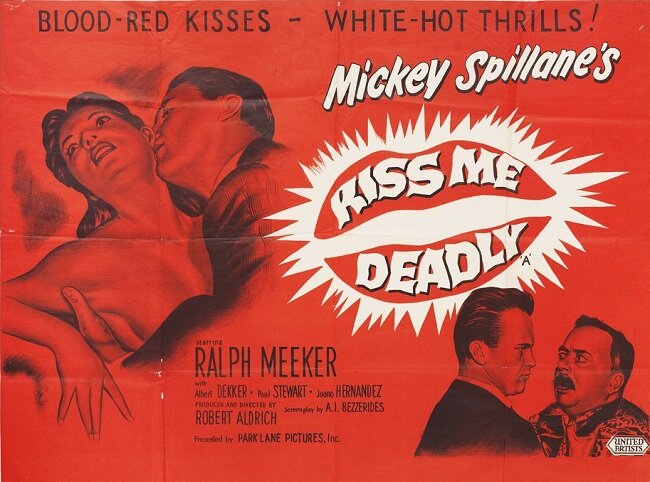

Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

Film Noir often reflects the numerous things that influenced it. German expressionism, French poetic realism and American hardboiled fiction. Hence many films from this genre have a tendency to be stylised both visually and narratively speaking, with a fatalistic tone. Kiss Me Deadly, directed by Robert Aldrich in 1955, takes all these attributes as well as others and amplifies them in one of the bleakest and most uncompromising movies of the fifties. It features a brutal protagonist who isn’t even a decent detective and a plot that seems at first glance to come straight out of Greek mythology. Yet Kiss Me Deadly is compelling and lean without any superfluous scenes or narrative baggage. There’s also what appears to be the mother of all cinematic "MacGuffins" but once the film is over and the viewer reflects upon what they have seen, it can be argued that maybe the characters and the inevitability of their actions are actually the driving plot device instead.

Film Noir often reflects the numerous things that influenced it. German expressionism, French poetic realism and American hardboiled fiction. Hence many films from this genre have a tendency to be stylised both visually and narratively speaking, with a fatalistic tone. Kiss Me Deadly, directed by Robert Aldrich in 1955, takes all these attributes as well as others and amplifies them in one of the bleakest and most uncompromising movies of the fifties. It features a brutal protagonist who isn’t even a decent detective and a plot that seems at first glance to come straight out of Greek mythology. Yet Kiss Me Deadly is compelling and lean without any superfluous scenes or narrative baggage. There’s also what appears to be the mother of all cinematic "MacGuffins" but once the film is over and the viewer reflects upon what they have seen, it can be argued that maybe the characters and the inevitability of their actions are actually the driving plot device instead.

P. I. Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) is driving his sports car one evening when he is forced to stop due to a woman running barefoot along the road, wearing nothing but a trench coat. He offers her a lift and she identifies herself as Christina (Cloris Leachman). She then asks him to "remember me", regardless of what happens next, alluding to a poem by Christina Rossetti. The pair are subsequently run off the road by unseen assailants. Hammer is knocked out in the crash and briefly comes round to find himself in a house where Christina is tortured to death. Hammer is then put back in his car along with Christina's body and the vehicle is pushed off a cliff. He awakes in hospital, to find his secretary Velda (Maxine Cooper) waiting for him. He decides to investigate Christina's murder believing that it "must be connected with something big." He subsequently tracks down Lily Carver (Gaby Rodgers), Christina's roommate. Lily tells Hammer she is hiding from sinister forces who are trying to find a mysterious box that, she believes, has contents worth a fortune.

Author Mickey Spillane created the character of Mike Hammer in 1946 and he was never intended to be as cerebral or as reflective as other hard boiled literary P.I.s such as Philip Marlowe. Director Robert Aldrich refines the character even further. In an early scene Christina makes an intuitive assessment of Hammer stating that he is the sort of man that “never gives in a relationship, who only takes”. And take he does. Hammer is a cheap private detective who usually does nothing more than squalid divorce cases. He often involves Velda in his work who does his dirty work out of love and devotion.Things he uses to his benefit. He also takes a beating. Regularly. Due to a plot conceit involving a suspended gun permit, Hammer never pulls a weapon. He only makes progress with his case because the villains of the story briefly consider using him to their advantage. Hammer is lacking in sophistication or breadth of vision. He is indeed like his name, a very specific tool and sees everything “as nails”. In many ways like the US foreign policy during the era.

Robert Aldrich was a radical film maker who smuggled his anti-establishment ideas in what many would assume were mainstream films. Kiss Me Deadly is not really a hard-boiled crime drama but a parable about the risks of nuclear proliferation with the clear metaphor of opening Pandora’s box. He shows how violence, allegedly an anathema to the righteous and virtuous, often becomes a convenient tool as they pursue their cause. Hammer casually destroys an Opera lover's record collection in front of him, relishing his discomfort. He also slams a drawer on an old man’s hand for “reasons”. Aldrich is also far more enamoured with his female characters. Their clearly marginalised status in 1950s America affords them a far more introspective and philosophical nature. Velda quickly grasps the magnitude of the mysterious box that is being sought by multiple parties, referring to it at the great “whatsit”. Christina knows that her fate is sealed the moment she strays into the affairs of men.

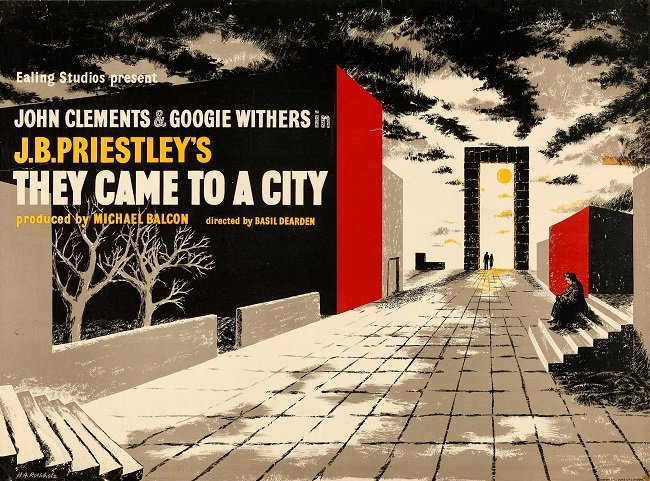

The script for Kiss Me Deadly by AI Bezzerides, a left leaning blacklisted screenwriter at the time, is very precise and minimalist. Something that a lot of modern writers need to learn. The sumptuous black and white cinematography by Ernest Laszlo is inherently classic yet reflects the modernity that post World War II America exulted. Perhaps the most memorable aspect of Kiss Me Deadly is its ending. Aldrich saves his best metaphor for last. Is Lily, like the United States, so obsessed with the power inherent with destruction, compelled to open the lid to satisfy her insatiable curiosity? The denouement still leaves an impression today and it has clearly influenced many other filmmakers. Steven Spielberg references it during the ending of Raiders of the Lost Ark. And the concept of an all powerful force in the trunk of a car was similarly adopted by Alex Cox in his 1984 science fiction movie Repo Man.

Oh look, that’s similar…