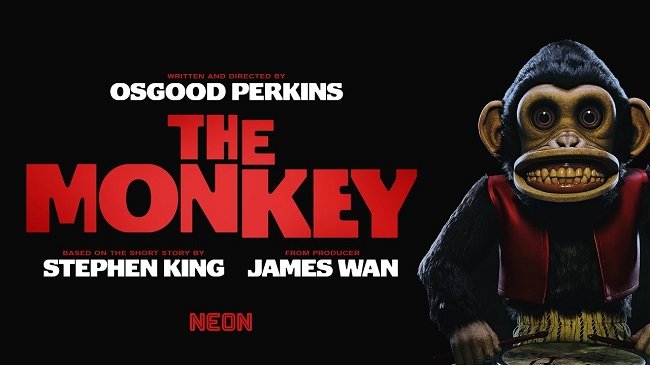

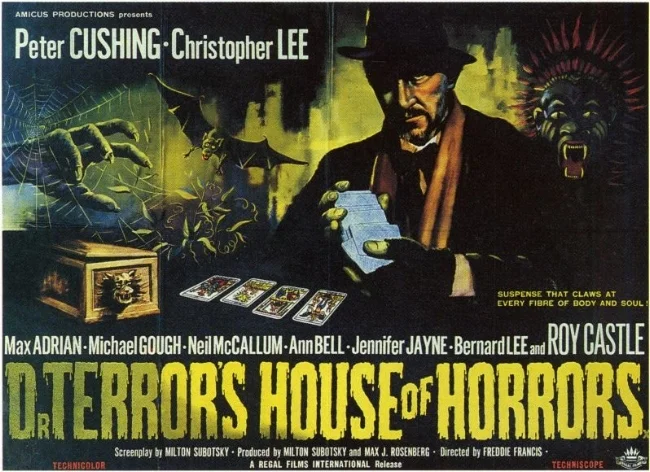

Dr. Terror's House of Horrors (1965)

Dr. Terror's House of Horrors was the first portmanteau horror movie by Amicus Productions. The small British studio was founded by producers and screenwriters Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg. As the horror genre grew in popularity due to the success of Hammer films, Amicus saw the potential in the portmanteau format. Subotsky in particular held Ealing Studios 1945 classic Dead of Night in very high regard. Although only a modest budget movie, Dr. Terror's House of Horrors proved to be financially successful and led to a series of similarly structured films over the next decade. These included Torture Garden (1967), The House That Dripped Blood (1970), Asylum (1972), Tales from the Crypt (1972), The Vault of Horror (1973), From Beyond the Grave (1974),

Dr. Terror's House of Horrors was the first portmanteau horror movie by Amicus Productions. The small British studio was founded by producers and screenwriters Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg. As the horror genre grew in popularity due to the success of Hammer films, Amicus saw the potential in the portmanteau format. Subotsky in particular held Ealing Studios 1945 classic Dead of Night in very high regard. Although only a modest budget movie, Dr. Terror's House of Horrors proved to be financially successful and led to a series of similarly structured films over the next decade. These included Torture Garden (1967), The House That Dripped Blood (1970), Asylum (1972), Tales from the Crypt (1972), The Vault of Horror (1973), From Beyond the Grave (1974),

Set on a late night train from London to Bradley, five passengers encounter a mysterious Dr Schreck (Peter Cushing) who offers to tell each passenger their future with a deck of Tarot cards. Initially most of them are sceptical, however curiosity eventually gets the better of them. As the Dr. proceeds, each man's story plays out as a vignette plays with a suitably sinister tone. All of which inevitably end unfavourably for the protagonists. Can the five passengers possibly escape their predicted demise? Will a fifth card drawn from the deck hold the key? Each time it is the death card; a conclusion they are far from happy with or ready to accept.

The most notable aspect of Dr. Terror's House of Horrors it its strong cast of British character actors. Jeremy Kemp, Bernard Lee and stately Christopher Lee effortlessly acquit themselves. A young Donald Sutherland was secured for the benefit of selling the movie to the US market. Roy Castle and Kenny lynch add some welcome levity to one story, without derailing the atmosphere. But ultimately it is Peter Cushing as the unshaven and shabby Dr. Schreck, who dominates the proceedings. He strikes the right balance between frailty and malevolence perfectly. The sinister look he gives when the first passenger (Neil McCallum) taps the Tarot card three time shows his prodigious acting talent.

As for the five stories that unfold, The Werewolf and Disembodied Hand are perhaps the strongest and the most traditionally grounded in horror. The others make up for in style what they lack in genuine horror. The Roy Castle's Voodoo tale is quite comic and reminiscent in tone to the Golfing story in Dead of Night. The Creeping Vine in which a family home is menaced by a sentient plant is surprisingly low key (due to minimal special effects) and works better that way. Vampire sees a newlywed Doctor who discovers that his wife may be a vampire. It has a rather clever sting in the tail. The resolution of the entire film holds yet another plot twist, though I'm sure it will come as no surprise to those familiar with this genre.

Despite its modest budget, this was considered a finely crafted horror vehicle at the time and had an X certificate rating. DVD copies currently available in the UK are now rated PG by the British Board of Film Classification. However it must be remembered that the British horror genre at the time was still in a state of transition. Hammer Studios had introduced more lurid elements to the proceedings but many films involving the supernatural still tended to rely on atmosphere and tone. Hence there is an emphasis on dialogue and performances in Dr. Terror's House of Horrors over gore. The atmospheric cinematography by Alun Hume (Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi, A View to a Kill) and the use of Techniscope elevate this mainly studio based production into something more than the average horror movie.

The portmanteau format proved lucrative for Amicus, mainly due to their focus on inventive writing and their stable of regular stars. The sub-genre fell out of favour in the late seventies as Hollywood scored box office success with blockbuster horror films such as The Exorcist and The Omen. However the influence of Dr. Terror's House of Horrors left its mark and occasionally film makers still try their hand with the multi-story format. The success of George Romero's Creepshow, based upon the baroque style of EC horror comics and Stephen King's Cat's Eye prompted a resurgence of the portmanteau horror in the mid-eighties. With the industries current penchant for rebooting past successes, perhaps we'll see a return of horror compilation.

Nightmares (1983)

Due to the commercial success of George A. Romero’s Creepshow in 1982 and the Twilight Zone: The Movie in 1983, there was a resurgence of anthology horror films in the eighties and nineties. Nightmares is one of many “portmanteau movies” that followed and is neither the worst, or the best that the genre has to offer. Originally conceived as a pilot for a NBC TV show, the completed film was deemed too “intense” for television and eventually released theatrically with an “R” rating. Judged by today’s standards, it is not especially violent and the strongest content is in the first chapter of the four part story. Written by Jeffrey Bloom and Christopher Crowe, both of whom have a background in popular seventies television, Nightmares has the look and feel of a TV production.

Due to the commercial success of George A. Romero’s Creepshow in 1982 and the Twilight Zone: The Movie in 1983, there was a resurgence of anthology horror films in the eighties and nineties. Nightmares is one of many “portmanteau movies” that followed and is neither the worst, or the best that the genre has to offer. Originally conceived as a pilot for a NBC TV show, the completed film was deemed too “intense” for television and eventually released theatrically with an “R” rating. Judged by today’s standards, it is not especially violent and the strongest content is in the first chapter of the four part story. Written by Jeffrey Bloom and Christopher Crowe, both of whom have a background in popular seventies television, Nightmares has the look and feel of a TV production.

The first story, Terror in Topanga, follows a homicidal patient who escapes from a mental institution and attacks a police officer. Meanwhile, chain smoking housewife Lisa (Christina Raines) drives to the local store to buy cigarettes. Will their paths cross? The second chapter, The Bishop of Battle, follows teenager J.J. (Emilio Estevez) obsessive battle to reach the mysterious thirteenth level of a video game in his local arcade. J. J. learns that all is not quite as it appears. The third chapter, The Benediction, stars Lance Henriksen as priest Frank MacLeod, who leaves his parish after a crisis of faith. He is stalked on a remote desert road by a black pickup truck that has murderous intent and potentially supernatural origins. The final chapter, Night of the Rat, features a suburban family (Richard Masur, Veronica Cartwright and Brigette Andersen) being menaced by a particularly large and intelligent rat.

Nightmares is efficiently directed by veteran filmmaker Joseph Sargent. However, the inherent problem with portmanteau films is ensuring that all stories are equally engaging. Sadly that is not the case here. Terror in Topanga is the most efficient of the four chapters. It sets out its stall and delivers a suitable climax to its story arc. But the next instalment, The Bishop of Battle is a major tonal shift from horror to fantasy and an obvious and uninspired tale. The Benediction offers a variation on an established theme (see Duel or The Car) but is carried by the presence of Lance Henriksen. Night of the Rat, which was intended to be the bravura ending to Nightmares, is somewhat stilted due to a weak script and an unlikeable lead character. Yet despite these inconsistencies Nightmares doesn’t out stay its 99 minute running time. It manages to get its pacing right. Something other anthologies often fail to do.

When viewed with a contemporary eye, Nightmares has some interesting points of interest. Setting aside the trope of the escaped murderer, Terror in Topanga uses smoking as a central plot device. Something that seems somewhat archaic today. The Bishop of Battle provides a window not only on arcade culture from the eighties but touches upon hardcore punk, with songs by Black Flag and Fear. The Benediction features a truck stunt that was used heavily in the marketing of the film. Such a thing would nowadays be done digitally, but here it is a physical effect and more impressive for it. Overall, Nightmares now serves mainly as a nostalgic reminder of the popularity of the anthology genre during the horror boom of the eighties. It is an amusing diversion for those well disposed towards such material and may play better to those who grew up during this era.

Tales of Terror (1962)

Directed by Roger Corman, Tales of Terror is an anthology horror film based upon three short stories by Edgar Allan Poe. “Morella”, “The Black Cat” and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar”. Adapted by Richard Matheson, the screenplay offers a ghoulish tale of revenge, a humorous story of a drunk who murders his wife and her lover and a sinister story of a mesmerist who hypnotises a terminally ill man at the point of death. Deftly produced and looking far more sumptuous than you’d expect from such a modest budget film, Tales of Terror benefits from a strong cast of old school, Hollywood character actors. The anthology format affords each story a fairly prompt and ghoulish climax and as ever with the films of Roger Corman from this period, visual creativity and innovation elevate the proceedings above the standard exploitation fare of the time.

Directed by Roger Corman, Tales of Terror is an anthology horror film based upon three short stories by Edgar Allan Poe. “Morella”, “The Black Cat” and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar”. Adapted by Richard Matheson, the screenplay offers a ghoulish tale of revenge, a humorous story of a drunk who murders his wife and her lover and a sinister story of a mesmerist who hypnotises a terminally ill man at the point of death. Deftly produced and looking far more sumptuous than you’d expect from such a modest budget film, Tales of Terror benefits from a strong cast of old school, Hollywood character actors. The anthology format affords each story a fairly prompt and ghoulish climax and as ever with the films of Roger Corman from this period, visual creativity and innovation elevate the proceedings above the standard exploitation fare of the time.

Tales of Terror is the fourth entry into the Roger Corman’s series of adaptations of the work of Edgar Allan Poe and the first to use the portmanteau format. Vincent Price makes a return after being absent in the previous entry Premature Burial which starred Ray Milland. Price demonstrates his acting prowess not only in three lead roles but by also providing the linking narration that frame all the stories. The short nature of each story doesn’t afford an opportunity for any in depth character development, hence the presence of a cast of robust and charismatic actors is invaluable in bolstering the narrative. The financial success of the previous instalments of the series meant that there was a greater budget available for the cast. Hence Price is joined by two stalwarts from the golden age of Hollywood; Peter Lorre and Basil Rathbone.

As ever with Corman productions, the production design by Daniel Haller is handsome and the sets are cleverly contrived to look more opulent than they actually are. Many have been recycled from previous production. Cinematographer Floyd Crosby, a long time collaborator of Roger Corman productions, lights the proceedings in an atmospheric way. This is especially noticeable in the last story, in which the mutlicoloured light used by mesmerist Mr. Carmichael (Basil Rathbone), bathes the actors in red, blue and yellow light in turn. There are also several sequences that use optical effects to distort the film image and give the stories a suitably supernatural ambiance. They also mask the basic nature of some of the make up effects. Legendary special effects artist Albert Whitlock created two notable matte paintings for the film. The Locke residence next to the sea and the Valdemar mansion nestled among the trees.

Tales of Terror presents an interesting change of approach from the earlier Roger Corman adaptations of the work of Edgar Allan Poe. The anthology format has both strengths and weaknesses. It provides a convenient means to swiftly build up to a climatic shock and offers three stories instead of one. Yet the strong cast have to rely on their established cinematic personalities to carry each story, as the script doesn’t offer much beyond what you see. Perhaps the most noticeable deviation from prior Poe adaptations is the humorous tone of the second story, The Black Cat. Peter Lorre is an amusing drunk and doesn’t really come across as a potential threat and murderer. However, despite this tonal shift, Tales of Terror remains a well crafted and enjoyable example of US Gothic horror form the sixties. Although similar in many ways to the UK’s Hammer productions, Corman’s work has a very different look and feel to it.

Tales That Witness Madness (1973)

I have a soft spot for portmanteau horror films, especially those made in the UK during the seventies. They often have an impressive cast of character actors and offer a snapshot of fashion, culture and sensibilities from the times. However, their weakness often lies with the inconsistency of the various stories. These can range from the outstanding, to what can best be described as filler. Furthermore, although the latter category have just as short a running time as the other vignettes, it is always the poor ones that seem to drag and disrupt the flow of the film. Tales That Witness Madness does not suffer too badly from this problem. Out of the four stories that are featured two stand out and two others are just average and not overtly bad. However, irrespective of potential narrative inconsistencies, there are some good ideas and a ghoulish streak running throughout the fill’s ninety minute running time.

I have a soft spot for portmanteau horror films, especially those made in the UK during the seventies. They often have an impressive cast of character actors and offer a snapshot of fashion, culture and sensibilities from the times. However, their weakness often lies with the inconsistency of the various stories. These can range from the outstanding, to what can best be described as filler. Furthermore, although the latter category have just as short a running time as the other vignettes, it is always the poor ones that seem to drag and disrupt the flow of the film. Tales That Witness Madness does not suffer too badly from this problem. Out of the four stories that are featured two stand out and two others are just average and not overtly bad. However, irrespective of potential narrative inconsistencies, there are some good ideas and a ghoulish streak running throughout the fill’s ninety minute running time.

Tales That Witness Madness is not an Amicus production but instead made by World Film Services. Efficiently directed by Freddie Francis, the framing story set in a high security psychiatric hospital sets an interesting tone. It is a brightly lit, modern environment and a far cry from the typical gothic asylums that are de rigueur in the horror genre. Jack Hawkins (dubbed by Charles Gray) and Donald Pleasance effortlessly navigate through their respective roles as two Doctors discussing cases. The first story, “Mr.Tiger”, is by far the weakest and is no more than the sum of its parts. A young boy has an imaginary friend who happens to be a tiger. It subsequently kills his parents who are constantly bickering. No explanation or deeper motive is provided. The second tale, “Penny Farthing”, packs a lot more into its duration including time travel, murder and a fiery denouement. It doesn’t make a lot of sense when thought about but it is a creepy vignette.

“Mel” is by far the oddest and most interesting story on offer. While out running Brian (Michael Jayston) finds a curious tree that has been cut down. He brings it home and places it in his lounge, much to his wife Bella’s annoyance (Joan Collins). Fascinated by the tree, which has the name Mel carved into it, he lavishes it with attention. Bella becomes jealous and decides to get rid of her rival. Naturally the story has a twist. There’s also a lurid dream sequence featuring Mel attacking Bella that predates The Evil Dead. The final story “Luau” about Auriol Pageant (Kim Novak) whose new client Kimo (Michael Petrovich) has designs on her daughter Ginny (Mary Tamm) is formulaic. The finale featuring a feast to appease a Hawaiian god is somewhat obvious. The climax of the framing story is also somewhat perfunctory but it does neatly conclude the proceedings.

The portmanteau horror sub genre has on occasions surpassed itself with such films as Dead of Night and Creepshow. But the inherent risk of providing a “visual buffet”, is that like the culinary equivalent, they’ll always be something you don’t like or that has been added because it’s cheap and easy. There is an element of this in Tales That Witness Madness. However, when reflecting upon not only British horror films from the seventies but other genres as well, one must remember that cinema was still a major source of entertainment and that a lot of the material was quickly produced to fill gaps in the market that TV could not provide at the time. With this in mind, Tales That Witness Madness may not be especially entertaining to the casual viewer. The more dedicated horror fan may find it more entertaining and of interest as an example of a specific sub genre that has fallen into decline in recent years.