Night of the Animated Dead (2021)

George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead is a true genre milestone that is praised not only by horror film fans but mainstream critics alike. If you are interested in watching an intelligent, well researched and entertaining documentary about the film’s provenance and cultural impact then I thoroughly recommend Birth of the Living Dead (2013) by Rob Kuhn. It tells you pretty much all you need to know about why this classic film is so important. As for Night of the Living Dead itself, it still holds up well after 53 years. It is the immediacy and relatability of the premise and overall story that still makes the film relevant. The zombies are purely a “MacGuffin” and the real focus of the plot is how people behave under pressure in life threatening situations. It’s a film about how we can react to the same situation differently and how cultural baggage and the need for people to be “right”, hinders co-operation and thwarts progress.

George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead is a true genre milestone that is praised not only by horror film fans but mainstream critics alike. If you are interested in watching an intelligent, well researched and entertaining documentary about the film’s provenance and cultural impact then I thoroughly recommend Birth of the Living Dead (2013) by Rob Kuhn. It tells you pretty much all you need to know about why this classic film is so important. As for Night of the Living Dead itself, it still holds up well after 53 years. It is the immediacy and relatability of the premise and overall story that still makes the film relevant. The zombies are purely a “MacGuffin” and the real focus of the plot is how people behave under pressure in life threatening situations. It’s a film about how we can react to the same situation differently and how cultural baggage and the need for people to be “right”, hinders co-operation and thwarts progress.

The legacy of Night of the Living Dead is far reaching. It turned zombies from a minor horror subset into an entire genre of their own and propagated the idea of the “zombie apocalypse”. A plot device that can be used to scrutinise and explore all the various facets of the human condition or to provide an endless litany of gore and body horror. The central premise of Romero’s film lends itself to reinvention and interpretation. It has already been officially “remade” in 1990 which added an interesting feminist angle to the story. And there have been numerous unofficial remakes and variations on the same theme from all over the globe. All add something to the basics of the story. Which brings me on to Night of the Animated Dead (2021). The title clearly sets out the film’s pitch. This is an animated feature film remake which closely follows the narrative structure of the original.

According to director Jason Axxin “This is a remake of the original movie. It’s essentially a way to make a classic more accessible to modern audiences. This is in color and there’s a lot more gore and violence. If you were ever hesitant to watch the original film, this is the version to see. It’s a fast-paced roller coaster ride of violence”. Frankly I find this statement and its premise somewhat spurious. Is Night of the Living Dead really outside of a modern audience's frame of reference? If so, that doesn’t say a lot for the average cinema goer. However, if we are to take Axxin’s comments in good faith, the only credible comparison I can come up with is that this version of Night of the Living Dead is intended to be the cinematic equivalent of a Reader’s Digest Condensed Books. A streamlined and somewhat lurid distillation of Romero’s vision. It is also devoid of any character and is possibly the most redundant film I’ve seen since Gus Van Sant’s remake of Psycho in 1998.

Despite having a competent voice cast, featuring Dulé Hill, Katharine Isabelle, Josh Duhamel, Nancy Travis, James Roday Rodriguez, Jimmi Simpson and Will Sasso, the animation style lacks any distinction or innovation. Classic scenes are lovingly recreated but the overall design slavishly adheres to that of the 1968 film and therefore fails to add anything new and say anything different. The minimalist style doesn’t really bring the story or themes into sharp relief and the character designs are somewhat lacking. The screenplay is credited to John A. Russo who wrote the original, as it is a verbatim summary of the 1968 version. The score by Nima Fakhrara is used sparingly and is evocative of the library music that Romero used. As for the “gore” it lacks any real impact due to its rather crude realisation. It comes off as a rather unnecessary embellishment.

I appreciate that there were probably budgetary restrictions that had an impact on the production. Setting aside such considerations, Night of the Animated Dead provides a simplified, less nuanced version of Night of the Living Dead. It hits all the essential beats of Romero’s classic but offers nothing beyond that other than its own inherent novelty. The animation is functional but far from accomplished. That said, Night of the Animated Dead is not an utter disaster. It manages to hold your interest. However, a film being mildly engaging due to its pointlessness is not really a great selling point. If you are a diehard horror fan who is curious to see an ill conceived project, then by all means watch Night of the Animated Dead. But I cannot recommend it in any way as a substitute to the original. At best it is just a minor footnote that serves to highlight the merits of the 1968 version and the talent of George A. Romero.

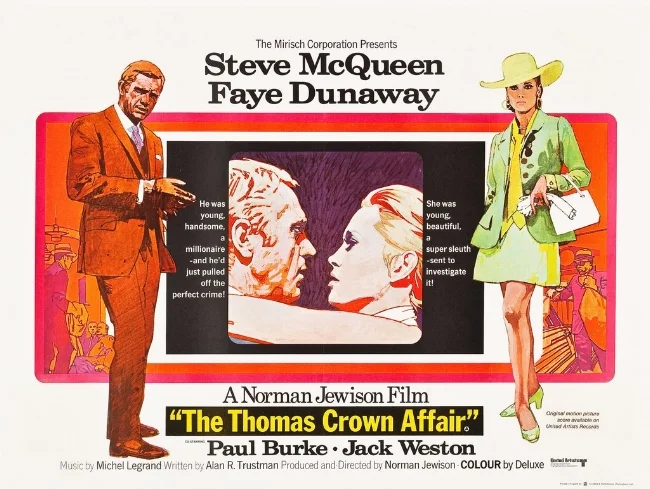

The Thomas Crown Affair (1968)

Millionaire businessman Thomas Crown (Steve McQueen) arranges for four men to steal $2,660,527.62 from a Boston bank. The men, who have never met before or seen Crown, successfully carry out the robbery. A fifth man then transports the stolen money and dumps it in a cemetery trash can. Crown retrieves the money, flies to Geneva and deposits it in a Swiss bank account. Eddy Malone (Paul Burke), the Boston police detective in charge of the case makes no progress until the bank’s insurance company assigns him one of their top investigators, Vicki Anderson (Faye Dunaway). Anderson thinks like a thief and works based upon her instincts. Looking through the evidence, she deduces that Crown is the culprit, potentially committing crimes just for amusement. Anderson subsequently meets Crown socially. Despite the situation and their respective positions, they are immediately attracted to each other and begin a relationship.

Millionaire businessman Thomas Crown (Steve McQueen) arranges for four men to steal $2,660,527.62 from a Boston bank. The men, who have never met before or seen Crown, successfully carry out the robbery. A fifth man then transports the stolen money and dumps it in a cemetery trash can. Crown retrieves the money, flies to Geneva and deposits it in a Swiss bank account. Eddy Malone (Paul Burke), the Boston police detective in charge of the case makes no progress until the bank’s insurance company assigns him one of their top investigators, Vicki Anderson (Faye Dunaway). Anderson thinks like a thief and works based upon her instincts. Looking through the evidence, she deduces that Crown is the culprit, potentially committing crimes just for amusement. Anderson subsequently meets Crown socially. Despite the situation and their respective positions, they are immediately attracted to each other and begin a relationship.

The Thomas Crown Affair is neo noir and a microcosm of Hollywood progressive cinema from the late sixties. It has a French cinematic aesthetic in its lighting and framing. Haskell Wexler’s cinematography is very fluid. The film makes extensive use of split screen and "multi-dynamic image technique", images shifting on moving panes. Director Norman Jewison directs confidently and with style focusing often on what is not being said, rather than what is. McQueen and Dunaway are charismatic and beautiful. They exude sex appeal and the pair carry what is essentially a dialogue light love story, through their onscreen presence. Noel Harrison’s performance of the song, The Windmills of Your mind, is suitably haunting and alludes to the complexities of Thomas Crown’s personality. It is all very arty, drawing upon all the prevailing cinematic trends and tropes of the time.

All of which is why I found The Thomas Crown Affair to be an interesting example of filmmaking from the sixties, rather than being an interesting film per se. Pop culture has evolved and the concept of the millionaire playboy and their “jet set” lifestyles is no longer universally admired and desired. Millionaires are now more often and not seen as Bond villains or at the very least, socially and emotionally dysfunctional. Hence the premise of The Thomas Crown Affair is dated with its self indulgent playboy master criminal. The more interesting aspect of the screenplay by Alan Trustman is the exploration of the “burden of wealth” and how having everything means you have nothing. Sadly, this is not explored sufficiently, as is the subplot about Crown’s dead wife. The bittersweet ending does work well and still rings very true. But the journey to this point is far too enamoured with presentation rather than feelings.

Perhaps the most problematic aspect of The Thomas Crown Affair is the soundtrack by French composer Michael Legrand. Norman Jewison originally wanted Henry Mancini to write the score for the film but he was unavailable and so recommended Legrand. His jazz heavy music was intentionally written for the rough cut of the film. Hence it had to be edited to fit on screen events in the final cut, which further makes the music an incongruous match. Plus jazz is a very broad church, musically speaking. Lalo Schifrin’s score for Bullitt, released the same year as The Thomas Crown Affair, is still cool as hell and funky. Legrands’ approach is far less melodic and far more kinetic. It is often very intrusive and frankly distracting. It ultimately makes a problematic film, even harder to watch for a modern audience. I may give the 1999 remake a watch to see if it handles the subject any better.

Yet More Cult Movie Soundtracks

Tenebrae (1982) is probably Dario Argento’s most accessible “giallo” for mainstream audiences. Although violent, it is not as narratively complex as Deep Red (1975) or as bat shit crazy as Phenomena (1985). The story centres on popular American novelist Peter Neal (Anthony Fanciosa) who is in Rome to promote his latest book. Events take a turn for the worst when a series of murders appear to have been inspired by his work. The plot twists and turns, the director explores themes such as dualism along with sexual aberration and blood is copiously spattered across the white walled interiors of modernist buildings. It is slick, disturbing and has a pounding synth and rock score by former Goblin members, Claudio Simonetti, Fabio Pignatelli, and Massimo Morante.

Tenebrae (1982) is probably Dario Argento’s most accessible “giallo” for mainstream audiences. Although violent, it is not as narratively complex as Deep Red (1975) or as bat shit crazy as Phenomena (1985). The story centres on popular American novelist Peter Neal (Anthony Fanciosa) who is in Rome to promote his latest book. Events take a turn for the worst when a series of murders appear to have been inspired by his work. The plot twists and turns, the director explores themes such as dualism along with sexual aberration and blood is copiously spattered across the white walled interiors of modernist buildings. It is slick, disturbing and has a pounding synth and rock score by former Goblin members, Claudio Simonetti, Fabio Pignatelli, and Massimo Morante.

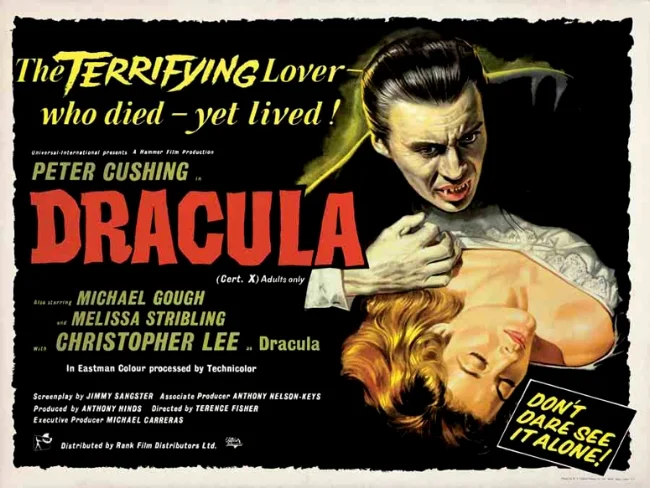

One Million Years B.C. (1966) is a delightful collaboration between Hammer Studios and stop motion animation legend Ray Harryhausen. It is the tale of how caveman Tumak (John Richardson) is banished from his native Rock tribe and after a long journey encounters the Shell tribe who live on the shores of the sea. It’s historically inaccurate, with dinosaurs, faux prehistoric languages and Raquel Welch in a fur bikini. It is also great fun and features a superbly percussive and quasi-biblical themed score by Italian composer Mario Nascimbene. Nascimbene was an innovator and often incorporated non-orchestral instruments and random noises, such as objects being banged together or clockwork mechanisms, into his music to underpin the stories it was telling. There is a portentous quality to his main opening theme as the earth is created and primitive man emerges.

Get Carter (1971) is a classic, iconic British gangster film featuring a smoldering performance by Michae Caine. The musical score was composed and performed by Roy Budd and the other members of his jazz trio, Jeff Clyne (double bass) and Chris Karan (percussion). The musicians recorded the soundtrack live, direct to picture, playing along with the film. Budd did not use overdubs, simultaneously playing a real harpsichord, a Wurlitzer electric piano and a grand piano. The opening theme tune, which plays out as Caine travels to Newcastle by train, is extremely evocative and enigmatic with its catchy baseline, pumping tabla and echoing keyboards. The music is innovative and a radical change from the established genre formula of the previous decade which often featured a full orchestral score.

Witchfinder General (1968) is an bleak and harrowing exploration of man’s inhumanity to man, presented in a very dispassionate fashion. Matthew Hopkins (Vincent Price) is an opportunistic “witch-hunter”, who plays upon the superstitions of local villagers in remote East Anglia and takes advantage of the lawless times, brought about by the English Civil War. Price’s performance is extremely menacing and his usual camp demeanour is conspicuously absent. Director Michael Reeves paints a stark picture of the treatment of women in the 17th century. Yet despite the beatings, torture and rape, composer Paul Ferris crafts a charming and melancholic soundtrack. There is a gentle love theme that has subsequently been used in the low budget Vietnam War film How Sleep the Brave (1981) and even featured an advert for Vaseline Intensive Care hand lotion in the late seventies.

Journey to the Far Side of the Sun AKA Doppelgänger (1969) is the only live action feature film that Thunderbirds creator, Gerry Anderson, produced. It is an intriguing, cerebral science fiction film in which a new planet is discovered in an identical orbit to that of earth but on the exact opposite side of the sun. A joint manned mission is hastily arranged by EUROSEC and NASA to send astronauts Colonel Glenn Ross (Roy Thinnes) and Dr John Kane (Ian Hendry) to investigate. Upon arrival the pair crash on the new planet in a remote and barren region. Ross subsequently awakes to find himself back on earth in a EUROSEC hospital. Exactly what happened and how is he back home? Journey to the Far Side of the Sun is like an expanded episode of the Twilight Zone and boasts great production design by Century 21 Studios under the direction of special effects genius Derek Meddings. The miniature work is outstanding. There is also a rousing score by longtime Anderson collaborator Barry Gray. Gray always expressed what was happening on screen quite clearly in his music, scoring in a very narrative fashion. The highlight of the film is a pre-credit sequence where scientist and spy Dr Hassler (Herbert Lom) removes a camera hidden in his glass eye and develops photographs of secret files. Gray’s flamboyant score featuring an Ondes Martenot works perfectly with the onscreen gadgetry and red light illumination of the dark room.

For further thoughts on cult movie music, please see previous posts Cult Movie Soundtracks and More Cult Movie Soundtracks.

The Legend of Hell House (1973)

There is a school of thought that the key to crafting a good horror or supernatural film lies with creating an atmosphere that impacts upon the viewer’s mind and emotions, rather than relying solely upon visual effects, gore and spectacle. Director Robert Wise clearly demonstrated this in his 1963 film The Haunting, based upon Shirley Jackson’s book The Haunting of Hill House. In many ways the film is seen as vindicating this particular theory. The Legend Of Hell House, made a decade later, is another example of this approach to genre film making. Directed by John Hough and written by Twilight Zone veteran and cult author Richard Matheson, it is another meticulously crafted piece of cinema with a focus on increasing tension and a sense of disquiet. Rather than intermittently scalding the viewer with jump scares, the film’s atmosphere is more akin to placing the audience in water and slowly bringing them to a boil.

There is a school of thought that the key to crafting a good horror or supernatural film lies with creating an atmosphere that impacts upon the viewer’s mind and emotions, rather than relying solely upon visual effects, gore and spectacle. Director Robert Wise clearly demonstrated this in his 1963 film The Haunting, based upon Shirley Jackson’s book The Haunting of Hill House. In many ways the film is seen as vindicating this particular theory. The Legend Of Hell House, made a decade later, is another example of this approach to genre film making. Directed by John Hough and written by Twilight Zone veteran and cult author Richard Matheson, it is another meticulously crafted piece of cinema with a focus on increasing tension and a sense of disquiet. Rather than intermittently scalding the viewer with jump scares, the film’s atmosphere is more akin to placing the audience in water and slowly bringing them to a boil.

Physicist Dr. Lionel Barrett (Clive Revill) is contracted by eccentric millionaire Mr. Deutsch to make an investigation into "survival after death". He must conduct his experiment in "the one place where it has yet to be refuted". The Belasco House, the "Mount Everest of haunted houses", originally owned by the notorious "Roaring Giant" Emeric Belasco. A six-foot-five perverted millionaire and alleged murderer, who disappeared soon after a massacre was discovered at his home. The house is believed to be haunted by numerous spirits, all victims of Belasco's twisted and sadistic desires. Accompanying Barrett are his wife, Ann (Gayle Hunnicutt), as well as two mediums. The first is mental medium and spiritualist minister Florence Tanner (Pamela Franklin) and the second is physical medium Benjamin Franklin "Ben" Fischer (Roddy McDowell). Ben is the only survivor of a previous investigation conducted 20 years before. All others involved either died or subsequently went mad.

British TV and film director John Hough had a very eclectic background prior to making this film. Yet despite only making one previous horror film (Twins of Evil for Hammer studios) he certainly shows a flair for the genre here. Using a very direct style bordering on a faux documentary, The Legend Of Hell House moves efficiently through its story. The Pre-credits sequence clearly sets out the film’s remit and then wastes no time in exploring it. It is not long before there is a seance with ectoplasm manifesting around Florence. And then both Florence and Ann are subject to nocturnal disturbances and whisperings. The spirit activity also plays heavily upon their sexual desires, especially Ann who is repressed. There are some intermittent jump scares and sudden jolts but Hough focuses more upon the characters reaction to the increasingly malevolent atmosphere, as the house itself preys upon each of the four researcher’s weaknesses.

Underpinning the proceedings is a discordant and sinister electronic score from former BBC Radiophonic workshop pioneers Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson. It is composed mainly of sounds and rhythms rather than traditional music and motifs and it works incredibly well. The cast are all on top form and acquit themselves well, especially McDowell. His calm demeanour hides the true horror of his previous experience at the Belasco House. There is a disquieting scene in which he finally lowers his psychic barriers to the evil presence. The camera spends several seconds holding McDowell in a close shot only for him to scream directly into the camera. Gayle Hunnicutt also gives a very sympathetic performance, as the spirit exploits her latent desires. Screenwriter Richard Matheson, who adapted his own novel, has toned down the sexual content and it is handled intelligently rather than explicitly. Viewers are made abundantly aware how human lust becomes a point of leverage by the force inhabiting the house.

The Legend Of Hell House remains a genuinely creepy and undeniably uneasy viewing experience. It explores the conflicts between traditional spiritualism and scientific enquiry into the so-called supernatural with an honest eye. The two make for curious bedfellows but this idea works well with the confines of this story. The ending is a curious blend of both methodologies which I felt was genuinely innovative. I would also like to note how the Blu-ray release of The Legend Of Hell House benefits greatly by having subtitles. They show what many of the inaudible whispering voices are saying which greatly enhances the story. Over the years The Legend Of Hell House has grown in reputation. It received mixed reviews upon its theatrical release in 1973 but has garnered more attention over time by critics who see it as a more cerebral work, rather than standard horror exploitation fodder. Discerning genre fans with an interest in noteworthy films should certainly add it to their watch list.

The Chairman (1969)

The Cold War was a mainstay of many a thriller and action movie throughout the sixties, seventies and eighties. However, all too often it was depicted in terms of the US versus the Soviet Union. China didn’t seem to feature so much, although it was just as equally an “enemy” of the West. Hence when I recently read about The Chairman (which has just had a Blu-ray release), it was of interest to me. An espionage story, starring Gregory Peck with a hidden bug implanted in his skull, infiltrating China to steal a secret enzyme formula is quite an intriguing premise. Furthermore, director J. Lee Thompson had previously worked with Peck on The Guns of Navarone, which is a solid action movie. Therefore I was initially optimistic that this film which I was previously unaware of, would be an interesting diversion. Unfortunately, having now seen The Chairman, all I can really describe it as is a cinematic curiosity. One of numerous films produced by a big studio in the late sixties that failed to satisfy anyone's expectations.

The Cold War was a mainstay of many a thriller and action movie throughout the sixties, seventies and eighties. However, all too often it was depicted in terms of the US versus the Soviet Union. China didn’t seem to feature so much, although it was just as equally an “enemy” of the West. Hence when I recently read about The Chairman (which has just had a Blu-ray release), it was of interest to me. An espionage story, starring Gregory Peck with a hidden bug implanted in his skull, infiltrating China to steal a secret enzyme formula is quite an intriguing premise. Furthermore, director J. Lee Thompson had previously worked with Peck on The Guns of Navarone, which is a solid action movie. Therefore I was initially optimistic that this film which I was previously unaware of, would be an interesting diversion. Unfortunately, having now seen The Chairman, all I can really describe it as is a cinematic curiosity. One of numerous films produced by a big studio in the late sixties that failed to satisfy anyone's expectations.

Nobel Prize-winning scientist Dr John Hathaway (Gregory Peck) receives a letter from a former Professor Soong Li (Keye Luke), who now resides in The People's Republic of China, requesting his assistance. Raising concerns with the US authorities, Hathaway is "invited" by Lt. General Shelby (Arthur Hill) to visit the Professor, who has allegedly developed an enzyme that allows crops to grow in any kind of climate. Hathaway subsequently agrees and finds himself embroiled in a joint operation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. A transmitter is implanted in Hathaway's skull which can be monitored by a satellite. He is not informed that the device also includes explosives that can be triggered by the Americans if necessary. Neither the U.S. nor the Soviet Union wants the enzyme to remain exclusively in Chinese hands. Hathaway flies to Hong Kong to request “authorisation” to visit China and meets Security Chief Yin (Eric Young) who is deeply suspicious of his motives.

The Chairman has high tech trappings, similar to those seen in The Forbin Project or even Fantastic Voyage. Staff sit at computers monitoring Hathaways pulse and respiration, big screens track his locations and military staff pace up and down drinking coffee from plastic cups. The basic premise is sound and Peck makes for an unlikely hero. But once the plot has been established, very little happens. Hathaway goes to Hong Kong, meets the shadowy figure of Yin and then is granted permission to travel to China. There is a brief diversion when a Chinese agent attempts to seduce him while another searches his apartment but nothing is made of the plot device. On arrival in China Peck is given an official tour of the country, with a few nods to the continuous military presence everywhere. He next meets Mao Tse Tung (the chairman of the communist party and leader of China) who needs his help in finding a way to mass produce the enzyme. They trade political views and philosophy over a game of table tennis.

Peck is always compelling to watch and it’s interesting to see a story which attempts to explore the fear of China at the time. But there simply isn’t sufficient to sustain the narrative. There is an action sequence at the end of the film when Hathaway flees the remote experimental compound with the help of a deep cover Soviet operative played by Burt Kwouk. There’s then a chase to the border and an attempt to penetrate the minefield and electrified fences. But it’s too little, too late. The film ends with all three superpowers sitting on the information they all share and Peck attempting to place the information in the public domain for the benefit of mankind. It is a suitable ending and the film is quite concise at 98 minutes but it all feels very undeveloped and unremarkable. The main point of note is a solid score by the ever dependable Jerry Goldsmith.

Red Tails (2015)

In 1944, the USAAF faces increased losses of Allied bombers conducting operations over Europe. The 332d Fighter Group (The Tuskegee Airmen), consisting of young African-American fighter pilots, are confined to ground attack missions in Italy and hampered with ageing, poorly maintained Curtiss P-40 Warhawk aircraft. After the Tuskegee Airmen distinguish themselves in support of the Allied landings at Anzio, Col. A.J. Bullard (Terence Howard) is surprised when the USAAF Bomber Command asks him if his men will escort the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers on their day time raids. Casualties have become unacceptably high. Bullard accepts on the condition his unit be supplied with the new North American P-51 Mustang. The tails of the new aircraft are painted bright red and become the unofficial name of the outfit. Bullard orders his pilots to remain with the bombers that they’re escorting and their first escort mission proves a success without the loss of a single bomber. Slowly, entrenched racist attitudes within the USAAF begin to change.

In 1944, the USAAF faces increased losses of Allied bombers conducting operations over Europe. The 332d Fighter Group (The Tuskegee Airmen), consisting of young African-American fighter pilots, are confined to ground attack missions in Italy and hampered with ageing, poorly maintained Curtiss P-40 Warhawk aircraft. After the Tuskegee Airmen distinguish themselves in support of the Allied landings at Anzio, Col. A.J. Bullard (Terence Howard) is surprised when the USAAF Bomber Command asks him if his men will escort the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers on their day time raids. Casualties have become unacceptably high. Bullard accepts on the condition his unit be supplied with the new North American P-51 Mustang. The tails of the new aircraft are painted bright red and become the unofficial name of the outfit. Bullard orders his pilots to remain with the bombers that they’re escorting and their first escort mission proves a success without the loss of a single bomber. Slowly, entrenched racist attitudes within the USAAF begin to change.

George Lucas is not known for his subtlety as a director, focusing more on visual flair than finely honed character development. Mercifully Red Tails does not do any sort of disservice to the memory of The Tuskegee Airmen. However, it doesn’t do them a great justice either. There are many aspects of the production that are outstanding, such as the ensemble cast featuring Nate Parker, David Oyelowo and Tristan Wilds and striking visual effects. But the weak link in the chain yet again is the screenplay by John Ridley and Aaron McGruder. It is laboured and pitched at a rather simplistic level. Subjects such as institutionalised bigotry, fascism and personal sacrifice need to be dignified with a bit more intelligence when depicted on screen. They are too important and complex issues to be portrayed in such an arbitrary fashion and sadly that is exactly how Red Tails plays out.

As a piece of populist entertainment, Red Tails works sufficiently. With the full weight of Industrial Light and Magic behind the visual effects, there is plenty of spectacle and the traditional story arc follows a distinctly tried and tested formula. The characters are engaging but this is predominantly due to the personalities of the respective actors. There is very little depth to the screenplay and the cast are mainly tasked with providing archetypes. The film will certainly play well to audiences who may not be so familiar with this aspect of World War II. The mixture of action and fast paced story should suit a youth demographic. But for the more sophisticated viewer, Red Tails will seem a bit light in content and lacking anything to make it distinctive. Portraying the Germans as “bad” because they are “Germans”, does not wash and seems a hangover from war films of the fifties. Furthermore the film seems to imply that after the success of The Tuskegee Airmen that the systemic problems of a segregated Air Force are effectively remedied. This sadly was not the case.

All films regardless of genre, require the suspension of disbelief by the audience to varying degrees and Red Tails is no different. Unfortunately George Lucas requires the audience not only to do this but to actively leave their common sense as home. You don’t have to be a military plane enthusiast to quibble over obvious technical inaccuracies or liberal bending of the laws of physics. One expects this to a degree in mainstream filmmaking but there are limitations. In this respect Red Tails does cross over the line. Ultimately, this could have been a superior film as opposed to just adequate, if a more seasoned director had been at the helm, armed with a more robust screenplay. One has to wonder exactly how much influence executive producer George Lucas had over various aspects of this production as Red Tails does exhibit the usual in-balance of content associated with his work.

The Marksman (2021)

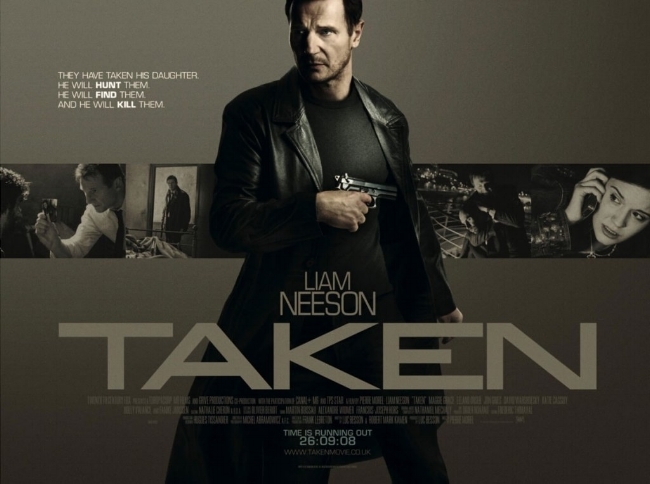

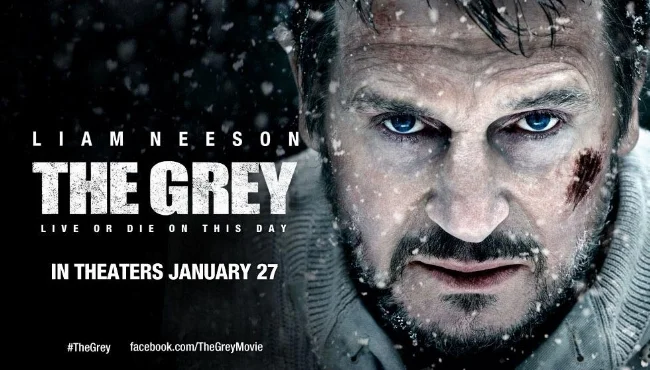

Former United States Marine Corps Scout Sniper and Vietnam War veteran Jim Hanson (Liam Neeson) lives on a ranch on the Arizona-Mexico border. The mortgage on the property is in arrears after the death of his wife has left him medically bankrupt. One day while patrolling his property he encounters Mother Rosa (Teresa Ruiz) with her son Miguel (Jacob Perez) illegally crossing the border fence. He calls his step daughter Sarah (Katheryn Winnick) in the border patrol and reports them as they’re miles from any habitation. However, Rosa and Miguel are fleeing a drug cartel and Mauricio (Juan Pablo Raba), one of their enforcers. When Mauricio and his men try to forcibly take Rosa, Jim intervenes and a car chase and firefight ensue. Mauricio’s brother is killed and Rosa is fatally wounded. She gives Jim a note with her family's address in Chicago and he reluctantly agrees to take Miguel there.

Former United States Marine Corps Scout Sniper and Vietnam War veteran Jim Hanson (Liam Neeson) lives on a ranch on the Arizona-Mexico border. The mortgage on the property is in arrears after the death of his wife has left him medically bankrupt. One day while patrolling his property he encounters Mother Rosa (Teresa Ruiz) with her son Miguel (Jacob Perez) illegally crossing the border fence. He calls his step daughter Sarah (Katheryn Winnick) in the border patrol and reports them as they’re miles from any habitation. However, Rosa and Miguel are fleeing a drug cartel and Mauricio (Juan Pablo Raba), one of their enforcers. When Mauricio and his men try to forcibly take Rosa, Jim intervenes and a car chase and firefight ensue. Mauricio’s brother is killed and Rosa is fatally wounded. She gives Jim a note with her family's address in Chicago and he reluctantly agrees to take Miguel there.

The various trailers and advertisements for The Marksman give the impression that this is an action film but that is not the case. This thoughtful, low key drama is far more of a character study of the relationship between Jim and Miguel. The film explores bereavement and loss, the plight of migrants across the US border and what happens when the “American Dream” turns bad. It bears a lot of similarities to Clint Eastwood’s A Perfect World (1993). Critics claims that the story is formulaic are indeed true and there are not many plot surprises along the way. However, the film’s strength lies in the two central performances which are both very good. There is genuine pathos as opposed to contrived sentimentality and again we are reminded that Neeson is a serious actor who reinvented himself as an action star. Plus it helps that Neeson can do “gruff” and “sad” with his eyes shut. He does much with the simple dialogue to establish his Rooster Cogburn credentials. “Nobody needs to call me, and I like it that way” he exclaims when asked why he doesn’t own a cell phone.

The Marksman is obviously made on a modest budget yet its cinematography by Mark Patten is handsome and makes the most of the vistas and scenery of Arizona and Wyoming. The film does a good job of conveying the immense size and often remote nature of the US border states. The action scenes are functional and do not strain the viewer's sense of credulity. Neeson is supposed to be an ageing Marine and not a special forces operative. He handles himself well in a fight but he also takes a beating. Everything of this nature remains within the confines of the film’s PG-13 rating which is fine as this is a story about characters bonding rather than breaking bones. Director Robert Lorenz has one final trick up his sleeve after teasing us with an action movie and giving us a character drama for 100 minutes. The ending, as Liam Neeson takes a bus to return home, is very reminiscent of Midnight Cowboy. It’s a little unexpected but in step with the film’s overall tone. The Marksman is by no means a masterpiece but is certainly better than its marketing campaign implied.

Minions (2015)

It would appear that there is a Minions 2, although it’s release around the world has been staggered due to the pandemic. So I thought I’d revisit the original movie for a second viewing. Spin-off movies can be a risky venture. Side characters may work well in a supporting role within a successful movie but may not necessarily find an audience in their own vehicle. However this is most definitely not the case with Minions. The movie is ninety one minutes of exquisitely crafted cinema. From the opening Universal fanfare (which the Minions sing-a-long to) to the post credit rendition of Revolution, the film is consistently funny and perfectly paced. The production design and overall aesthetic is beautifully realised and the central characters of Kevin, Stuart and Bob are thoroughly engaging. Actually, forget "engaging ''. They are genuinely loveable. Directors Pierre Coffin and Kyle Balda barely put a foot wrong.

It would appear that there is a Minions 2, although it’s release around the world has been staggered due to the pandemic. So I thought I’d revisit the original movie for a second viewing. Spin-off movies can be a risky venture. Side characters may work well in a supporting role within a successful movie but may not necessarily find an audience in their own vehicle. However this is most definitely not the case with Minions. The movie is ninety one minutes of exquisitely crafted cinema. From the opening Universal fanfare (which the Minions sing-a-long to) to the post credit rendition of Revolution, the film is consistently funny and perfectly paced. The production design and overall aesthetic is beautifully realised and the central characters of Kevin, Stuart and Bob are thoroughly engaging. Actually, forget "engaging ''. They are genuinely loveable. Directors Pierre Coffin and Kyle Balda barely put a foot wrong.

Set in 1968, the Minions are in an emotional decline as they cannot find a master to serve. So Kevin, Stuart and Bob set off from home to find the biggest and baddest villain around with a view of becoming their henchmen. They chance upon international criminal Scarlet Overkill (Sandra Bullock) and due to good luck, inadvertently win her favour. If they can secure the Queen of England's crown for her, then Scarlet will find a home for them and restore them to their rightful role as henchmen. This broad plot lends itself to a wealth of sixties pop culture references and clever in-joke, along with continual slapstick humour. This is a movie that entertains on multiple levels which explains why the adults outnumbered the children in the screening I saw back in 2015.

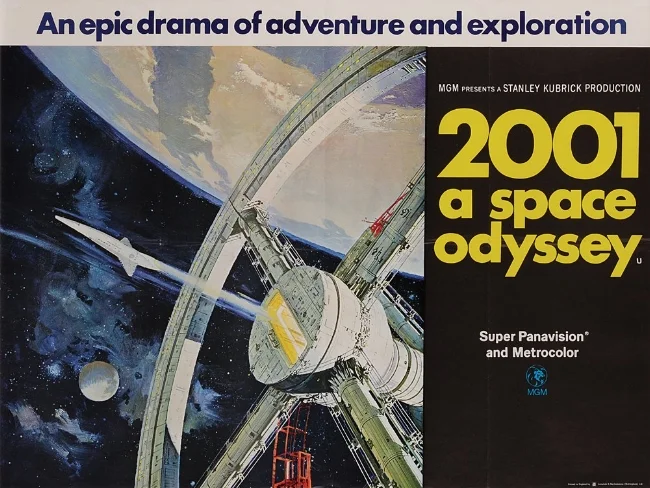

During the course of their misadventures Kevin, Stuart and Bob drive through a movie set where Stanley Kubrick is faking the Moon Landing, get walked over by The Beatles at the Abbey Road zebra crossing and pull the sword Excalibur from the stone, thus claiming the throne of England. Minions is the sort of movie that requires multiple viewings to fully appreciate all it's throwaway gags and one liners. I spotted a great deal more second time round. The period setting also lends itself to a cornucopia of classic tunes by the likes of The Who, The Kinks and The Rolling Stones. Are they clichéd? Yes. Do they still work? Most certainly due to the way they superbly underscore the onscreen action.

I laughed continuously while watching Minions and was more than happy to surrender myself to its inherent stupidity and tangential narrative. The minions themselves are extremely likeable. There is no need for them to possess complex character traits or to have convoluted motivations beyond their Joie de vivre and penchant for bananas. This most certainly has been the funniest movie I've seen for a while and I felt immensely restored by seeing it. Laughter really does have curative properties and there is simply so much material to see here. Oh and if you do decide to watch Minions, stay right until the end and ensure you watch all the credits and beyond. You'll be well rewarded. Let us hope that the sequel delivers more of the same.

The Fourth Protocol (1987)

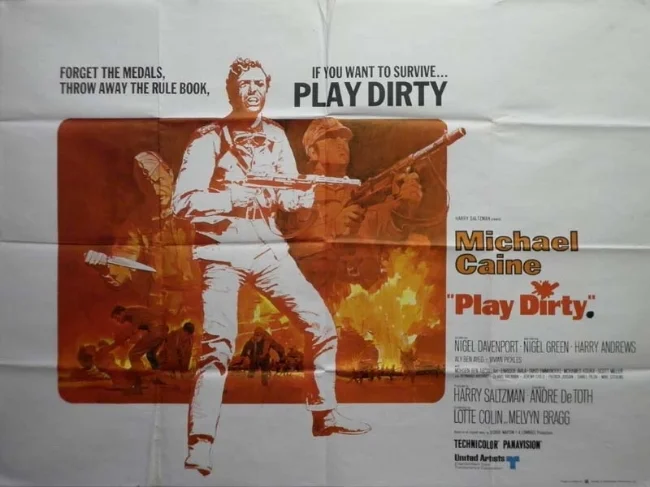

Sometimes a perfectly competent film simply misses the boat. The Fourth Protocol is a prime example of this. Based upon the novel by Frederick Forsythe this well made, somewhat clinical thriller arrived in cinemas at a time when the cold war was coming to an end due to “glasnost” and the “red menace” was becoming a somewhat tired plot device. It didn’t help that a similar story about a rogue Russian mission to detonate a nuclear device on a US base had already featured four years earlier in the Bond film, Octopussy. Michael Caine spent several years trying to get the project off the ground, after initially reading the author’s draft manuscript of the novel. Veteran screenwriter George Axelrod was hired and John Frankenheimer was sought to direct the film. However, difficulties in financing the project led to changes in the production and Forsythe ended writing the screenplay himself, while John Mackenzie (The Long Good Friday) took on the direction.

Sometimes a perfectly competent film simply misses the boat. The Fourth Protocol is a prime example of this. Based upon the novel by Frederick Forsythe this well made, somewhat clinical thriller arrived in cinemas at a time when the cold war was coming to an end due to “glasnost” and the “red menace” was becoming a somewhat tired plot device. It didn’t help that a similar story about a rogue Russian mission to detonate a nuclear device on a US base had already featured four years earlier in the Bond film, Octopussy. Michael Caine spent several years trying to get the project off the ground, after initially reading the author’s draft manuscript of the novel. Veteran screenwriter George Axelrod was hired and John Frankenheimer was sought to direct the film. However, difficulties in financing the project led to changes in the production and Forsythe ended writing the screenplay himself, while John Mackenzie (The Long Good Friday) took on the direction.

MI5 officer John Preston (Michael Caine) discovers that British government official George Berenson (Anton Rodgers) is leaking government documents. Although his investigation is well received by British Secret Service official Sir Nigel Irvine (Ian Richardson), Preston's methods embarrass the acting Director of MI5, Brian Harcourt-Smith (Julian Glover) and he is reassigned to "Airports and Ports". Meanwhile in Russia, KGB General Yevgeny Karpov (Ray MacAnally) suspects that his immediate superior, General Gavorshin (Alan North) is mounting an unauthorised operation. He discovers that Major Valeri Petrofsky (Pierce Brosnan) has recently assumed a long established fake identity and been dispatched to the UK. In the meantime, Preston investigates the death of a Russain merchant seaman who was run over while trying to leave port without authorisation. While searching through his personal affects he discovers a metal disk. This is subsequently identified as polonium, which could be used as part of a detonator for an atomic bomb.

The Fourth Protocol has a very similar feel to The Day of the Jackal, insofar that it is procedurally driven and plays at times more like a faux docudrama rather than thriller. The fact they’re both written by the same author is obviously relevant. In the case of The Fourth Protocol, this very procedural approach to Preston’s investigation, juxtaposed with Petrofsky’s methodical collection of the various bomb parts, does come somewhat at the expense of character development. This is a film mainly about archetypes and political themes common to the spy genre. However the film does offer some great detail such as when Berenson (Anton Rodgers) is followed by an MI5 surveillance team across London. Petrofsky’s elimination of casual witnesses is also quite grim. The practicalities of creating a nuclear bomb are also starkly presented, although certain aspects of the process are ignored for practical and narrative reasons.

Caine and Brosnan do much of the heavy lifting and keep the drama afloat. The latter does very well considering he does have a minimal amount of dialogue. Caine has some smart one liners that he delivers with relish and the scene where he forensically deals with two skinheads on the London Underground who are racially harassing a passenger is spot on. The film has some very good yet somewhat low key stunts. The scene where Caine and his MI5 sidekick drive directly onto a platform at King’s Cross station and Caine leaps onto the moving train is well handled. The fact that it's executed within a single tracking shot makes it all the more impressive. The film also benefits from a solid score by Lalo Schifrin which underpins the action and enhances the drama. All in all, this is a solid thriller which keeps the viewer engaged for nearly two hours. Unfortunately, timing is important and public tastes change. Hence The Fourth Protocol was just a few years too late and didn’t quite make its mark.

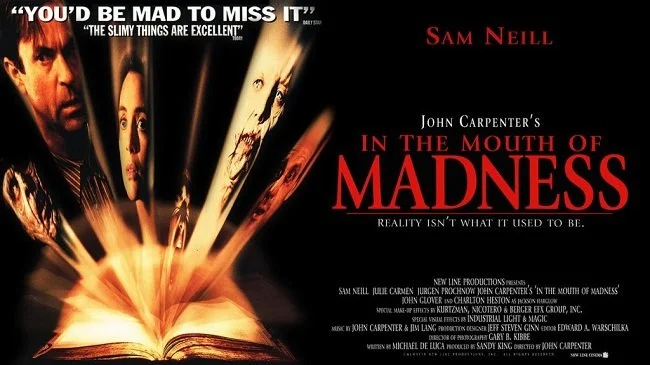

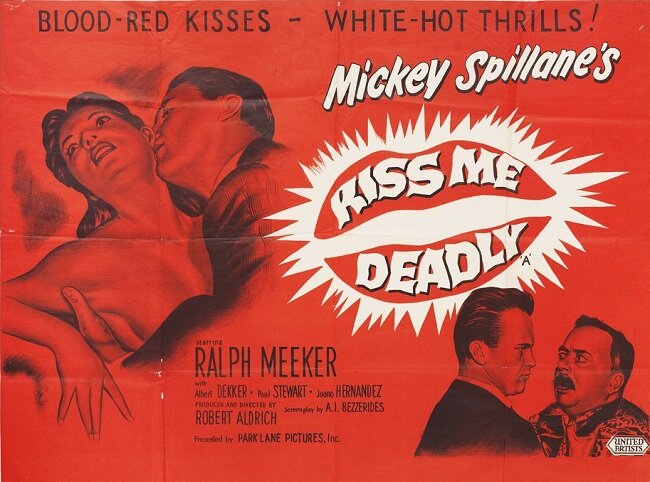

Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

Film Noir often reflects the numerous things that influenced it. German expressionism, French poetic realism and American hardboiled fiction. Hence many films from this genre have a tendency to be stylised both visually and narratively speaking, with a fatalistic tone. Kiss Me Deadly, directed by Robert Aldrich in 1955, takes all these attributes as well as others and amplifies them in one of the bleakest and most uncompromising movies of the fifties. It features a brutal protagonist who isn’t even a decent detective and a plot that seems at first glance to come straight out of Greek mythology. Yet Kiss Me Deadly is compelling and lean without any superfluous scenes or narrative baggage. There’s also what appears to be the mother of all cinematic "MacGuffins" but once the film is over and the viewer reflects upon what they have seen, it can be argued that maybe the characters and the inevitability of their actions are actually the driving plot device instead.

Film Noir often reflects the numerous things that influenced it. German expressionism, French poetic realism and American hardboiled fiction. Hence many films from this genre have a tendency to be stylised both visually and narratively speaking, with a fatalistic tone. Kiss Me Deadly, directed by Robert Aldrich in 1955, takes all these attributes as well as others and amplifies them in one of the bleakest and most uncompromising movies of the fifties. It features a brutal protagonist who isn’t even a decent detective and a plot that seems at first glance to come straight out of Greek mythology. Yet Kiss Me Deadly is compelling and lean without any superfluous scenes or narrative baggage. There’s also what appears to be the mother of all cinematic "MacGuffins" but once the film is over and the viewer reflects upon what they have seen, it can be argued that maybe the characters and the inevitability of their actions are actually the driving plot device instead.

P. I. Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) is driving his sports car one evening when he is forced to stop due to a woman running barefoot along the road, wearing nothing but a trench coat. He offers her a lift and she identifies herself as Christina (Cloris Leachman). She then asks him to "remember me", regardless of what happens next, alluding to a poem by Christina Rossetti. The pair are subsequently run off the road by unseen assailants. Hammer is knocked out in the crash and briefly comes round to find himself in a house where Christina is tortured to death. Hammer is then put back in his car along with Christina's body and the vehicle is pushed off a cliff. He awakes in hospital, to find his secretary Velda (Maxine Cooper) waiting for him. He decides to investigate Christina's murder believing that it "must be connected with something big." He subsequently tracks down Lily Carver (Gaby Rodgers), Christina's roommate. Lily tells Hammer she is hiding from sinister forces who are trying to find a mysterious box that, she believes, has contents worth a fortune.

Author Mickey Spillane created the character of Mike Hammer in 1946 and he was never intended to be as cerebral or as reflective as other hard boiled literary P.I.s such as Philip Marlowe. Director Robert Aldrich refines the character even further. In an early scene Christina makes an intuitive assessment of Hammer stating that he is the sort of man that “never gives in a relationship, who only takes”. And take he does. Hammer is a cheap private detective who usually does nothing more than squalid divorce cases. He often involves Velda in his work who does his dirty work out of love and devotion.Things he uses to his benefit. He also takes a beating. Regularly. Due to a plot conceit involving a suspended gun permit, Hammer never pulls a weapon. He only makes progress with his case because the villains of the story briefly consider using him to their advantage. Hammer is lacking in sophistication or breadth of vision. He is indeed like his name, a very specific tool and sees everything “as nails”. In many ways like the US foreign policy during the era.

Robert Aldrich was a radical film maker who smuggled his anti-establishment ideas in what many would assume were mainstream films. Kiss Me Deadly is not really a hard-boiled crime drama but a parable about the risks of nuclear proliferation with the clear metaphor of opening Pandora’s box. He shows how violence, allegedly an anathema to the righteous and virtuous, often becomes a convenient tool as they pursue their cause. Hammer casually destroys an Opera lover's record collection in front of him, relishing his discomfort. He also slams a drawer on an old man’s hand for “reasons”. Aldrich is also far more enamoured with his female characters. Their clearly marginalised status in 1950s America affords them a far more introspective and philosophical nature. Velda quickly grasps the magnitude of the mysterious box that is being sought by multiple parties, referring to it at the great “whatsit”. Christina knows that her fate is sealed the moment she strays into the affairs of men.

The script for Kiss Me Deadly by AI Bezzerides, a left leaning blacklisted screenwriter at the time, is very precise and minimalist. Something that a lot of modern writers need to learn. The sumptuous black and white cinematography by Ernest Laszlo is inherently classic yet reflects the modernity that post World War II America exulted. Perhaps the most memorable aspect of Kiss Me Deadly is its ending. Aldrich saves his best metaphor for last. Is Lily, like the United States, so obsessed with the power inherent with destruction, compelled to open the lid to satisfy her insatiable curiosity? The denouement still leaves an impression today and it has clearly influenced many other filmmakers. Steven Spielberg references it during the ending of Raiders of the Lost Ark. And the concept of an all powerful force in the trunk of a car was similarly adopted by Alex Cox in his 1984 science fiction movie Repo Man.

Oh look, that’s similar…

Keeping a Popular Franchise Relevant

I’ve written in the past about “how long should a TV show run for” and it remains a very interesting talking point. An ageing cast and a played out formula are not uncommon problems that can lead to a popular show being cancelled. But some long standing TV dramas have different issues that can blight them. Such as overly complicated lore, a vocal fanbase and a need to stay relevant in a way that some other shows don’t have to worry about. Martin Belam has recently written a very good article about this subject. He cites Doctor Who as a show that is extremely fatigued at present and suggests that maybe taking it off air and having some time out may well be the solution to its “problems”. I agree with him. Not only with regard to Doctor Who but basically any TV or movie franchise that has become ubiquitous and therefore tired as a result.

I’ve written in the past about “how long should a TV show run for” and it remains a very interesting talking point. An ageing cast and a played out formula are not uncommon problems that can lead to a popular show being cancelled. But some long standing TV dramas have different issues that can blight them. Such as overly complicated lore, a vocal fanbase and a need to stay relevant in a way that some other shows don’t have to worry about. Martin Belam has recently written a very good article about this subject. He cites Doctor Who as a show that is extremely fatigued at present and suggests that maybe taking it off air and having some time out may well be the solution to its “problems”. I agree with him. Not only with regard to Doctor Who but basically any TV or movie franchise that has become ubiquitous and therefore tired as a result.

Here are a few select quotes that I think are pertinent. Again these are specifically about Doctor Who but are equally applicable to comparable shows.

“Sometimes it feels like the show is being buried under the weight of its own continuity”.

“The decision to cast a woman as the Doctor has also meant the franchise became a pawn in the culture wars, further souring relationships in the fandom, and making the social media posts of the show’s creators and stars toxic to wade through”.

“It feels as if it is telling an increasingly self-absorbed meta-story about its own run, accompanied by a very vocal online fandom that isn’t quite sure what it wants, but knows it doesn’t want this”.

Doctor Who has been absent from our televisions in the past. It lost its way back in the middle to late eighties and was taken off air when audiences started declining. The sixteen year hiatus certainly made a difference and when it returned in 2005 it had totally reinvented itself and found exactly the right tone for a modern audience. James Bond is another prime example. The franchise has taken time out twice to rethink its direction. GoldenEye (1995) put the franchise back on track after the excesses of the Roger Moore era (The two Dalton movies were a change of tone too quickly). And Casino Royale (2006), possibly the best realisation of the character from the original text, made Bond relevant again after the franchise started losing ground to its competitors. However, taking a break doesn’t always guarantee an improved return. Dare I mention a certain franchise set in a galaxy, far, far away.

It is easy to see why owning a popular franchise is appealing to a TV network or film studio. Once established they become known quantities that need to be managed and curated. Spinoffs offer potential new content and do not pose the same risk as completely new products. You only have to look at Disney + to see a textbook example of such portfolio management. The BBC is not in such a position with Doctor Who. It doesn’t have the finances unless it goes into business partnership with a third party. Such a collaboration could potentially reinvigorate the franchise. But there is also equal scope for it to go the other way. A major US backer would naturally want a product tailored to its domestic market. All things considered, if Doctor Who doesn’t rethink its current direction it is destined to repeat the same mistakes of the late eighties, become a caricature of itself and get cancelled. Perhaps it is better to jump, than be pushed. A short hiatus may well be the solution.

The Sea Wolves (1980)

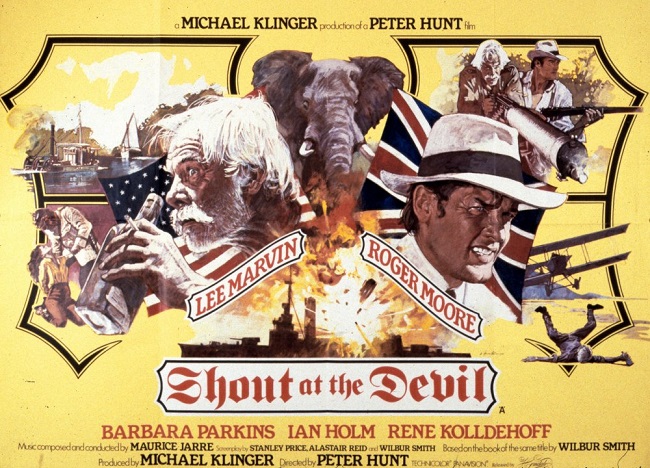

I have always had a soft spot for the action movies that Euan Lloyd produced in the late seventies and early eighties. The Wild Geese (1978), The Sea Wolves (1980), Who Dares Wins (1982) and Wild Geese II (1985). They were quite gritty and all had a strong cast of British character actors. Sadly some of them strayed into political issues with their stories and often got out of their depths. The Wild Geese ham-fistedly explores the political landscape of post colonial Africa and Who Dares Wins clumsily deals with terrorism and the concept of unilateral nuclear disarmament. Yet despite the somewhat school boy approach to geopolitics, the action scenes are well crafted (often by legendary Bond stunt arranger Bob Simmons) and the cast more than make up for any narrative failings. All four films also have charismatic soundtracks by Roy Budd. However The Sea Wolves differs from the other three movies in so far that it is set during World War II and is loosely based on real events.

I have always had a soft spot for the action movies that Euan Lloyd produced in the late seventies and early eighties. The Wild Geese (1978), The Sea Wolves (1980), Who Dares Wins (1982) and Wild Geese II (1985). They were quite gritty and all had a strong cast of British character actors. Sadly some of them strayed into political issues with their stories and often got out of their depths. The Wild Geese ham-fistedly explores the political landscape of post colonial Africa and Who Dares Wins clumsily deals with terrorism and the concept of unilateral nuclear disarmament. Yet despite the somewhat school boy approach to geopolitics, the action scenes are well crafted (often by legendary Bond stunt arranger Bob Simmons) and the cast more than make up for any narrative failings. All four films also have charismatic soundtracks by Roy Budd. However The Sea Wolves differs from the other three movies in so far that it is set during World War II and is loosely based on real events.

During World War II, many British merchant ships are being sunk by German U-boats. British intelligence, based in India, believe that the information is being passed to the U-boats by a radio transmitter hidden on board one of three German merchant ships interned in the neutral Portuguese colony of Goa. Lieutenant-Colonel Pugh (Gregory Peck) of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) is tasked with finding the German spy passing the shipping information and destroying the radio transmitter onboard the interned ships. Accompanied by fellow operative Captain Gavin Stewart (Roger Moore), the pair travel to Goa to attempt to capture a high level German spy known as Trompeta (Wolf Kahler). After he dies during a struggle, Pugh decides to make a daring raid on the interned ships in Goa harbour. Due to Portugal's neutrality SOE cannot use British troops. So Pugh asks Colonel W.H. Grice (David Niven), the commanding officer of a Territorial unit of British expatriates called the Calcutta Light Horse, if they would carry out the mission covertly. They all volunteer as they are all ex-service men and keen to 'do their bit'.

The Sea Wolves is a very traditional high adventure movie directed by veteran filmmaker Andrew V. McLaglen. The film’s strength lies with its strong cast featuring the likes of Trevor Howard, Patrick Macnee and Patrick Allen. The script is functional and has occasional moments of droll dialogue, usually based around the age of the various old soldiers complaining about their aches and pains. The locations are interesting and the production design does a good job of recreating the period. Furthermore, the miniature effects by Kit West and Nick Allder are top drawer and the action scenes are credible, well edited and entertaining. The Sea Wolves eschews the cliched cinematic conceit of the German cast speaking English, instead opting for authentic dialogue and subtitles. Yet despite many positive elements, the film drags during the turgid romance between Captain Stewart and divorcee (and German spy) Agnes Cromwell (Barbara Kellerman).

Roger Moore was 52 when he was cast in The Sea Wolves and he was clearly losing his boyish good looks. Yet the film industry still insisted upon casting him as a romantic lead. He continued with Bond well after his best before date and frankly it showed. In this instance his torrid affair is very much written in the idiom of the times and it is as dull as ditch water. The plot grinds to a halt during these scenes. Furthermore critics at the time made a big deal out of Gregory Peck’s English accent but I’ve heard far worse over the years and don’t consider it to be a deal breaker. It should be remembered that to finance such a British production Euan Lloyd needed a known star that would clearly appeal to the US market. Peck was such an actor and works well in the role. He certainly shines in his scene with David Niven who he worked with previously on The Guns of Navarone.

Film’s about World War II proved a mainstay of the UK and US box office for over 30 years. However interest waned eventually as a new generation of cinema viewers, who were born in the post war years, became the principal audience. Films that have revisited this historical period since then have tended to take a more revisionist approach to the subject matter. The Sea Wolves is one of the last old school, “for King and country” style of action movie. Perhaps that is why it didn’t fare as well at the box office as other Euan Lloyd productions. He personally blamed this on the demise of co-financier Lorimar Pictures and their poor marketing. I think that audiences simply wanted something more contemporary, as proved by Who Dares Wins. Viewed with a modern perspective The Sea Wolves does seem somewhat dated in its tone. However, it can still prove entertaining and certainly offers an unusual story, set away from the European theatre of war.

Assassin’s Creed (2016)

On paper, a video games franchise such as Assassin’s Creed lends itself perfectly to a cinematic adaptation. The parkour action scenes, the historical settings and the contemporary conspiracy theory themes are all elements that should play well with a modern youth audience. Hence with the backing of a major studio such as Twentieth Century Fox and a budget of $125 million, the 2016 movie should have been a guaranteed box office hit. The casting of Michael Fassbender, an actor who is comfortable with serious roles and big Hollywood franchises, should have carried this film comfortably over the finishing line. Director Justin Kurzel, who had found critical success with his adaptation of MacBeth a year previously, must have looked like a safe pair of hands to handle such a project. Sadly, that was not the case. Assassin’s Creed is not the sum of its parts, in fact many elements appear to be pulling in opposite directions. The resulting feature film is staggeringly dull, soulless and a chore to watch. A testament to how modern big budget franchise movies have become a production line, with all the art stripped from them.

On paper, a video games franchise such as Assassin’s Creed lends itself perfectly to a cinematic adaptation. The parkour action scenes, the historical settings and the contemporary conspiracy theory themes are all elements that should play well with a modern youth audience. Hence with the backing of a major studio such as Twentieth Century Fox and a budget of $125 million, the 2016 movie should have been a guaranteed box office hit. The casting of Michael Fassbender, an actor who is comfortable with serious roles and big Hollywood franchises, should have carried this film comfortably over the finishing line. Director Justin Kurzel, who had found critical success with his adaptation of MacBeth a year previously, must have looked like a safe pair of hands to handle such a project. Sadly, that was not the case. Assassin’s Creed is not the sum of its parts, in fact many elements appear to be pulling in opposite directions. The resulting feature film is staggeringly dull, soulless and a chore to watch. A testament to how modern big budget franchise movies have become a production line, with all the art stripped from them.

Convicted murder, Callum Lynch (Michael Fassbender), is sentenced to death by lethal injection in a prison in Texas. He awakes from his execution to find himself very much alive and in a high tech research laboratory in Madrid, run by the Abstergo Foundation and its sinister CEO Alan Rikkin (Jeremy Irons). Dr. Sofia Rikkin (Marion Cotillard) explains to Cal that she wishes to access inherited memories hidden in his DNA, of his ancestor Aguilar de Nerha, who was a member of the Assassins Brotherhood in 15th Century Spain. Abstergo Industries is actually funded and controlled by the Templars, an ancient order that has been at war with the Assassins Brotherhood for centuries. They seek the Apple of Eden, an artefact that holds the code to humanity’s ability for free will, which they seek to control. Cal is placed in the Animus, a machine which allows him to relive (and the scientists to observe) Aguilar's genetic memories, so that Abstergo can learn what he did with the Apple. Aguilar was previously charged with protecting the artefact from Templar Grand Master Tomas de Torquemada.

Within minutes of the film’s opening sequence which is set in 1492 Andalusia, the muddy colour palette and swooping camera it becomes clear that Assassin’s Creed has been shot using all the visual styles and editing techniques that are currently in vogue. It is the sort of movie where all concerned are far more enamoured by the aesthetic they have created rather than presenting the audience with a coherent and engaging narrative. Naturally, the production design and visual effects are top draw as you would expect from a mainstream film with this sort of budget. Yet the entire movie is presented in a singularly unappealing fashion and unfolds in a ponderous manner. The colours are muted, the camera refuses to stay still, inducing a sense of motion sickness. The editing is so rapid it often renders the onscreen action incomprehensible and the imagery strikes hard upon the senses. It is also clear that the film has chosen this technique to mask and reduce the levels of violence, so it can maintain the desired PG-13 rating.

There are three writers credited with the screenplay for Assassin’s Creed. Michael Lesslie, Adam Cooper and Bill Collage. Yet despite their efforts the story is perfunctory and the central characters are utterly forgettable. Action movies never used to be like this. In 1981 Raiders of the Lost Ark featured a wealth of interesting, enjoyable characters and the screenplay was savvy, filled with knowing genre references and droll, hard boiled dialogue. There is none of that here and a cast of solid actors are saddled with the most arbitrary of expository dialogue. Brendon Gleason has a cameo as Michael Fassbender’s Father. The relatively short role is supposed to provide an emotional epiphany within the story and create a sense of pathos but it is devoid of any dramatic resonance. It simply serves as an expostionary scene to move the story on. As for the more philosophical aspects of the plot regarding free will and determinism, these are abandoned immediately after they are mentioned.

Assassin’s Creed offers several clear nods to its source material. The costume design, hidden blades, parkour and historical setting certainly tap into the vibe of the first two games. The realisation of the Animus is also creative. Yet irrespective of the money and talent that is involved in the production, the film is staggeringly unexciting. In many ways it is a textbook example of all the artistic failings of corporate film making these days. Too much of our popular entertainment, be it music, TV or film are generic and made to an established formula. 40 years ago summer blockbusters were not only commercially successful but artistically created with flair and panache. The homogenous nature of their modern counterparts robs them of any unique personality of their own. For example, Assassin’s Creed runs for nearly 2 hours and features a musical score by Jed Kurzel that is essentially forgettable. I still recall the impact that James Horner’s soundtrack for Krull (1983) had upon me when I first saw it and it remains a personal favourite all these years later

Assassin’s Creed made a total profit of $240,697,856 internationally. It nearly doubled its investment yet was deemed a box office failure by those that financed it. A similar mindset is prevalent in the video game industry. Expectations regarding profit are often ambitious to say the least. Considering how poor the final movie is, I suspect that the entire project was a litany of continuous interventions by focus groups and sub-committees. So in many ways the studios are the architects of their own problem. To those who have a serious interest in cinema and are curious to see an example of when a film inherently fails on all levels, I would recommend Assassin’s Creed as a point of study. Beyond this niche market analysis, I cannot think of any positive points for the benefit of the casual viewer. Avid fans of the games will more than likely be disappointed as there is no exploration of their themes beyond the very superficial. Perhaps the failure of Assassin’s Creed will at least encourage the industry to rethink its approach to such movies and the wider action genre.

The Sparks Brothers (2021)

The music business is a strange, interesting and broad church. A spectrum of musical styles and personalities all fulfilling the needs of different markets. There are pop stars who are buoyant but ephemeral. Then there are singer/songwriters who take their work seriously as they express their critique of the human condition via their music. There are also style icons, novelty acts, indie bands, lounge crooners and a myriad of other niche acts, all doing their own thing. And occasionally there are enigmas. Artists and bands that fly in the face of prevailing trends and commercial interest, who do consider their work to be an artistic endeavour and an expression of themselves and as such, do not see the virtue of personal compromise or corporate interests. Esoteric musicians who reinvent themselves continuously as they grow and age. Constantly defying the expectations of both their own fans and naysayers. Sparks are such a musical entity and the subject of a fascinating documentary by director Edgar Wright.

The music business is a strange, interesting and broad church. A spectrum of musical styles and personalities all fulfilling the needs of different markets. There are pop stars who are buoyant but ephemeral. Then there are singer/songwriters who take their work seriously as they express their critique of the human condition via their music. There are also style icons, novelty acts, indie bands, lounge crooners and a myriad of other niche acts, all doing their own thing. And occasionally there are enigmas. Artists and bands that fly in the face of prevailing trends and commercial interest, who do consider their work to be an artistic endeavour and an expression of themselves and as such, do not see the virtue of personal compromise or corporate interests. Esoteric musicians who reinvent themselves continuously as they grow and age. Constantly defying the expectations of both their own fans and naysayers. Sparks are such a musical entity and the subject of a fascinating documentary by director Edgar Wright.

Sparks, created by brothers Ron and Russell Mael, are musical chameleons. During the course of their five decade long career they have flirted with rock, synth pop and the art song but always in their own unique and idiosyncratic way. They’re the very definition of a cult band who have often charted a course parallel to that of mainstream music. Yet their influence is far reaching as they very much appear to be “your favourite band’s favourite band”. The Sparks Brothers attempts to explore all these things in an energetic and surprisingly droll fashion. Director Edgar Wright, explains their appeal in part by emphasizing its essential nebulous and arcane nature. The documentary follows a simple chronological path from the brothers early life and first forays into music then continues to delineate their seminal albums and changes of musical direction over the ensuing years. Ron and Russell are clearly intelligent, talented and conscious of their own enigma. They are also very witty and personable. There are no divas here, just hardworking disciplined artists, intent on doing their thing.

Sparks’s public image is clearly defined and is possibly one of few constants about the duo. It is also one of contrasts. Vocalist Russell’s athletic physique, flowing locks and matinee-idol looks are contrasted by brother Ron and his gangrel deportment, deadpan countenance and Brilliantined hair. He has always sported a moustache that is somewhere between that of Charlie Chaplin and Adolf Hitler. Russell’s falsetto voice and energetic on stage antics are further offset by Ron’s static performance as he sits at his keyboard exuding a miasma of curious strangeness. During the course of their career the brothers have made genuinely creative videos and their stage shows have bordered on performance art. Hence they have an appeal that reaches across musical genres and sexual demographics. All while singing about Sherlock Holmes, breasts and other eclectic subjects. Over the years their music has featured rock guitar riffs, synth arpeggios and infuriatingly catchy baroque song structures that draw upon classical composers such as Bach and Beethoven.

One of the most interesting aspects of The Sparks Brothers is the way the guest talking heads try to assess them and express their befuddlement at trying to pin them down. Nick Heyward candidly states “I thought they didn’t really exist” after he saw them in the flesh, out and about. Jonathan Ross describes their uniqueness and how they eschewed the traditional band image. “They look like people who’ve been sort of let out for a day”. Franz Ferdinand lead singer, Alex Kapranos, touches upon a commonly held misconception about the band “I always thought Sparks were a British Band” mainly because it seemed unlikely that the US could spawn an act so eccentric. The Sparks Brothers successfully sheds some light on the duo, who despite their European sound and anglophile nature were raised in California. Russell was surprisingly a high-school quarterback. Their father, an artist, seems to have had a major influence upon the brothers instilling a love of music, cinema and art. He tragically died when Ron was 11 and Russell 8.

Edgar Wright, the director of quirky and intelligent films such as Shaun of the Dead and Baby Driver is eminently suited to document and dissect a band such as Sparks. In many ways they are kindred spirits and therefore both have a strong understanding of each other. Wright also has a proven track record of understanding music as he has used it so intelligently in his body of work. He manages to look beyond the band’s eccentric schtick and gets some very honest opinions out of them. They’re surprisingly unpretentious despite their somewhat esoteric body of work. They just think that music is more than just a disposable commodity and it is frankly very refreshing the way they constantly strive to do something different. They certainly do not seem to be disposed toward resting upon their laurels or retiring anytime soon.

The Sparks Brothers may be a little long for the casual viewer. Some may tire of the celebrity endorsements and find it a little borderline “lovies, darlings” but I would counter that with the relevance of being recognised and admired by your peers, rather than mainstream media. I deem one to be more significant and genuine than the other. The documentary references many of their best songs and I was surprised at how many I was directly or subconsciously familiar with. I even bought a 3 CD “best of” boxset as a result. Even if you’re not completely sold on the Mael brother’s brand of music, I can wholeheartedly recommend the documentary just as a study on genuine creativity and artistic integrity. Both are rare commodities these days. And for your edification, here is the song Something for the Girl With Everything which is pretty much Sparks in a nutshell. The tune is catchy but unusual and the lyrics are a psychologist's dream.

Something for the girl with everything

See, the writing's on the wall

You bought the girl a wall

Complete with matching ball-point pen

You can breathe another day

Secure in knowing she won't break you (yet)

Something for the girl with everything

Have another sweet my dear

Don't try to talk my dear

Your tiny little mouth is full

Here's a flavour you ain't tried

You shouldn't try to talk, your mouth is full

Something for the girl with everything

Three wise men are here

Three wise men are here

Bearing gifts to aid amnesia

She knows everything

She knows everything

She knew you way back when you weren't yourself

Here's a really pretty car

I hope it takes you far

I hope it takes you fast and far

Wow, the engine's really loud

Nobody's gonna hear a thing you say

Something for the girl with everything

Three wise men are here

Three wise men are here

Where should they leave these imported gimmicks

Leave them anywhere, leave them anywhere

Make sure that there's a clear path to the door

Something for the girl with everything

Something for the girl with everything

Something for the girl with everything

Something for the girl with everything

Three wise men are here

Three wise men are here

Three wise men are here

Three wise men are here

Here's a partridge in a tree

A gardener for the tree

Complete with ornithologist

Careful, careful with that crate

You wouldn't want to dent Sinatra, no

Something for the girl who has got everything,

Yes everything

Hey, come out and say hello

Before our friends all go

But say no more than just hello

Ah, the little girl is shy

You see of late she's been quite speechless, very speechless

She's got everything

300: Rise of an Empire (2014)

300: Rise of an Empire is a curious beast, being neither a sequel nor a prequel. It is infact a tale that takes place simultaneously with those of the original movie. While Gerard Butler is busy making a last stand at the Battle of Thermopylae, fellow warrior and politician Themistokles, played by the singularly uncharismatic Sullivan Stapleton, leads a similar army of buffed Greeks against the Persian fleet. Once again we have a movie that is the epitome of style over substance, complete with a sound design that challenges what can physically be endured by human hearing. They say the first casualty of war is innocence but in this type of movie it's closely followed by historical accuracy and authentic depictions of ethnicity. 300: Rise of an Empire is a cinematic assault upon the senses but not in a good way like Mad Max: Fury Road.

300: Rise of an Empire is a curious beast, being neither a sequel nor a prequel. It is infact a tale that takes place simultaneously with those of the original movie. While Gerard Butler is busy making a last stand at the Battle of Thermopylae, fellow warrior and politician Themistokles, played by the singularly uncharismatic Sullivan Stapleton, leads a similar army of buffed Greeks against the Persian fleet. Once again we have a movie that is the epitome of style over substance, complete with a sound design that challenges what can physically be endured by human hearing. They say the first casualty of war is innocence but in this type of movie it's closely followed by historical accuracy and authentic depictions of ethnicity. 300: Rise of an Empire is a cinematic assault upon the senses but not in a good way like Mad Max: Fury Road.