Conspiracy (2001)

Conspiracy is a 2001 co-production between the BBC and HBO, that dramatises the events of the Wannsee Conference of 1942. Based upon secret minutes of the meeting, the drama explores the businesslike manner in which the German State decided and implemented the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question" during World War II. Set in a confiscated lakeside villa in the Berlin borough of Wannsee, the plot unfolds around a conference table. The screenplay by Loring Mandel is free from theatrics and hyperbole. Instead it focuses upon a chilling meeting in which genocide is calmly debated in the same way as armament quotas or economic growth. Frank Pierson’s direction is straightforward and uncomplicated allowing the viewer to dwell on the manner and tone of the proceedings. Conspiracy features an ensemble cast, including Kenneth Branagh as Reinhard Heydrich, Stanley Tucci as Adolf Eichmann, Colin Firth as Dr Wilhelm Stuckart and an early appearance by Tom Hiddleston.

Conspiracy is a 2001 co-production between the BBC and HBO, that dramatises the events of the Wannsee Conference of 1942. Based upon secret minutes of the meeting, the drama explores the businesslike manner in which the German State decided and implemented the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question" during World War II. Set in a confiscated lakeside villa in the Berlin borough of Wannsee, the plot unfolds around a conference table. The screenplay by Loring Mandel is free from theatrics and hyperbole. Instead it focuses upon a chilling meeting in which genocide is calmly debated in the same way as armament quotas or economic growth. Frank Pierson’s direction is straightforward and uncomplicated allowing the viewer to dwell on the manner and tone of the proceedings. Conspiracy features an ensemble cast, including Kenneth Branagh as Reinhard Heydrich, Stanley Tucci as Adolf Eichmann, Colin Firth as Dr Wilhelm Stuckart and an early appearance by Tom Hiddleston.

Conspiracy achieves much, considering the scope and implications of the subject matter. It manages to juggle a dozen characters, all of whom are from distinct and diverse backgrounds with clear agendas of their own. Soldiers, government officials and civil servants all seem to view the “final solution” as an administrative, logistical and legal problem. Dr Rudolph Lange (Barnaby Kay) states how execution by shooting is bad for troops' morale. It is an incongruous comment that focuses on psychological welfare of those conducting mass murder. Yet the screenplay successfully provides insight into this broad group’s motivations. Heydrich is shown to be a consummate manipulator as he cajoles and coerces all present into towing the official party line. It soon becomes clear that the decision to commit genocide had already been taken and that this meeting was not designed to agree it but to officially implement it and bind all present to the undertaking by collective involvement.

Conspiracy is a difficult film to watch, in that the magnitude of what is being discussed verges upon the incomprehensible. Performances are universally strong and compelling. There are several key incidents that occur that indicate the inevitability of the proposed “final solution”. Those looking to legitimise the proceedings legally are forced to abandon such a position. One bureaucrat even considers the implementation of this policy as being beneficial to his career. But perhaps the most chilling of all of these is the way in which Heydrich makes all present complicit with the decision, binding them by guilt. And then once the task is complete, all attendees calmly depart back to their regular jobs and posts. Heydrich comments about moving into the villa in which the conference has been held, once the war is over. Conspiracy ends with a summary of what happened to those attending the Wannsee Conference. Many were acquitted by Allied military tribunals after the war and lived the remainder of their lives in West Germany.

His House (2020)

If you are labouring under the erroneous assumption that the horror films are apolitical and devoid of wider social commentary, then I suggest you go and watch Dawn of the Dead, Get Out or Pan’s Labyrinth. The horror genre has for many years been addressing social issues and cultural foibles. So the timely arrival of His House comes as no major surprise. Immigration has become more than a point of debate in recent years, having been usurped and subverted by tabloid hyperbole and populist rhetoric. However, this horror thriller film written and directed by Remi Weekes indulges in none of the negative traits associated with the subject. It intelligently weaves social themes into an atmospheric and disquieting genre tale. Although in many ways the ground that His House treads is classic ghost story territory, it is both the perspective of Sudanese culture and the trauma of their migrant journey that make this such a fresh and engaging film.

If you are labouring under the erroneous assumption that the horror films are apolitical and devoid of wider social commentary, then I suggest you go and watch Dawn of the Dead, Get Out or Pan’s Labyrinth. The horror genre has for many years been addressing social issues and cultural foibles. So the timely arrival of His House comes as no major surprise. Immigration has become more than a point of debate in recent years, having been usurped and subverted by tabloid hyperbole and populist rhetoric. However, this horror thriller film written and directed by Remi Weekes indulges in none of the negative traits associated with the subject. It intelligently weaves social themes into an atmospheric and disquieting genre tale. Although in many ways the ground that His House treads is classic ghost story territory, it is both the perspective of Sudanese culture and the trauma of their migrant journey that make this such a fresh and engaging film.

Bol (Sope Dirisu) and Rial (Wunmi Mosaku) are refugees fleeing from the civil war in South Sudan. While crossing the Mediterranean, a sudden storm causes their overcrowded boat to sink. Many drown including Bol and Rial’s daughter Nyagak. After spending 3 months in a UK refugee centre the couple are granted probational asylum. They are assigned a dilapidated inner city house and given strict instructions not to move or seek employment or they face potential deportation. Their case worker Mark (Matt Smith), tells them the house is “better than what he got” and how he hopes the couple are one of "the good ones". However, soon after moving in nocturnal disturbances, noises and bad dreams afflict Bol and Rial. Bol desperately wants to fit in and stubbornly refuses to acknowledge the presence of the supernatural. But Rial wants to return home and feels there is no place for them in the UK. Has something followed them from South Sudan and are the couple harbouring a secret?

His House covers a lot of ground and works on multiple levels. If you’re just looking for a tense horror then it provides exactly that and has the added bonus of referencing non-european superstitions and supernatural folklore. The digital effects are surprisingly creative and most effective during several dream sequences depicting Bol and Rial’s dangerous sea crossing. There is a strong sense of unease to be found both inside and outside of the house as the story progresses. When the scare’s come they hit home effectively and the film has a very strong sound design. Also throughout the story there is a robust streak of real social horror but it is intelligently explored. Bol is automatically followed by security when he visits a discount department store. The UK immigration service is depicted as indifferent to the couple’s emotional trauma. And in a very bold move, Rial is racial abused by a black British youth and told to “go back to Africa”. His House also works as a tale exploring the loss of a child and the conflict it causes between the grieving couple.

But at the heart of the story, driving it forward are the compelling performances by Sope Dirisu and Wunmi Mosaku. They are a plausible, vulnerable and very likeable couple. British writer-director Remi Weekes handles the proceeding assuredly and delivers a well timed curveball two thirds into the film, which puts the events in a different perspective. The story’s conclusion manages to avoid being overtly bleak but instead reflects upon reconciliation and coming to terms with the past. It has been a while since I have seen such a universally strong directing debut and I am eager to learn what Remi Weekes’ next project is going to be. His House is a fine example of how the horror genre can deftly explore more than just the supernatural. It also provides some robust and innovative scares, as well as a very timely contemporary storyline that leaves you thinking long after you’ve finished viewing.

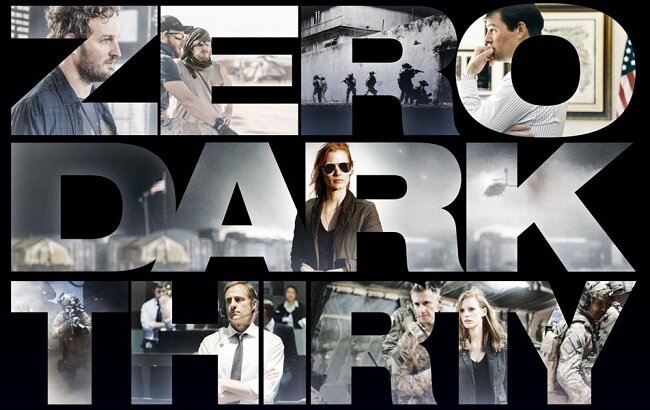

Zero Dark Thirty (2012)

I did not watch Zero Dark Thirty upon its initial release, due to the politics surrounding it. I wanted to be able to view it free from bipartisan debate. Eight years on I believe this now achievable and although debate still exists it is now more measured and less strident. Zero Dark Thirty is certainly a compelling movie. It plays as a docudrama, providing an in-depth study of the US intelligence services hunt for Osama Bin Laden. It cannot be faulted on a technical level and the performances are very strong. It does not adopt a celebratory or triumphalist tone in its approach to the story. Director Kathryn Bigelow endeavours to keep the proceedings focused upon the intricacies of an intelligence driven manhunt. There is little or no tubthumping, jingoism. The decision to find Bin Laden is shown as a political and military exercise of foreign policy. The film solely focuses on the story from a US perspective but that is perfectly acceptable as it is not intended to be an exploration of geo-politics.

I did not watch Zero Dark Thirty upon its initial release, due to the politics surrounding it. I wanted to be able to view it free from bipartisan debate. Eight years on I believe this now achievable and although debate still exists it is now more measured and less strident. Zero Dark Thirty is certainly a compelling movie. It plays as a docudrama, providing an in-depth study of the US intelligence services hunt for Osama Bin Laden. It cannot be faulted on a technical level and the performances are very strong. It does not adopt a celebratory or triumphalist tone in its approach to the story. Director Kathryn Bigelow endeavours to keep the proceedings focused upon the intricacies of an intelligence driven manhunt. There is little or no tubthumping, jingoism. The decision to find Bin Laden is shown as a political and military exercise of foreign policy. The film solely focuses on the story from a US perspective but that is perfectly acceptable as it is not intended to be an exploration of geo-politics.

Do not expect to see all the traditional elements of narrative cinema in Zero Dark Thirty. CIA operative Maya (Jessica Chastain) is a driven woman but this is not really explored to any degree, because it is not the focus of the plot. Because she is a senior employee of the CIA, we simply have to assume that she is a patriot and hence culturally traumatised by the events of September 11th. All characters are presented in a similar fashion. We follow their actions and processes, as opposed to scrutinising their personalities and motivations. This is very much a movie about "how" and not "why". A lot is left to the viewer to consider and decide for themselves, should they see fit to do so. Such as is the use of torture effective? Was the US government right to invest so much resources into hunting one man? Was the death of Osama Bin Laden of any real military relevance or simply an act of national closure and political opportunism?

The final act of the movie reconstructs the Navy SEAL raid on the compound at Abbottabad. Those expecting a traditional action sequence will be disappointed. Technically accurate, it is bereft of all the faux melodrama usually associated with Hollywood's depiction of such events. It is depressingly plausible and in some ways anti-climatic. That is not to say that the part of the film is without suspense. It just has an overwhelming air of inevitability. A sentiment that seems to be felt by all involved as the decade long operation reaches its conclusion. The cast as well as the audience are left to ponder, was this a real victory or had its meaning ultimately been lost? Zero Dark Thirty ends it's two and a half hour journey on a note of emotional ambiguity. It makes for strangely fascinating viewing but does no more than present the viewer with the "facts", although there are hints at where the filmmaker's feelings lie.

The Cloverfield Paradox (2018)

Cloverfield (2008) was a surprise hit, earning $172 million worldwide at the box office against a $25 million budget. Paramount Pictures naturally wanted a sequel but director Matt Reeves and writer Drew Goddard struggled to find a suitable narrative means to progress the original story. Both eventually left the project and the production descended into development hell. The subsequent success of Godzilla and Pacific Rim saw the Kaiju genre becoming oversaturated and so the decision to make a direct sequel was re-evaluated. Eventually a “speculative screenplay” called The Cellar was purchased and repurposed to include some additional science fiction elements and became 10 Cloverfield Lane. Despite being a curious genre hybrid which only tenuously links to the original movie, this too fared well at the box office. Therefore it was inevitable that a third movie in the so-called “Cloververse” would follow.

Cloverfield (2008) was a surprise hit, earning $172 million worldwide at the box office against a $25 million budget. Paramount Pictures naturally wanted a sequel but director Matt Reeves and writer Drew Goddard struggled to find a suitable narrative means to progress the original story. Both eventually left the project and the production descended into development hell. The subsequent success of Godzilla and Pacific Rim saw the Kaiju genre becoming oversaturated and so the decision to make a direct sequel was re-evaluated. Eventually a “speculative screenplay” called The Cellar was purchased and repurposed to include some additional science fiction elements and became 10 Cloverfield Lane. Despite being a curious genre hybrid which only tenuously links to the original movie, this too fared well at the box office. Therefore it was inevitable that a third movie in the so-called “Cloververse” would follow.

Due to an emerging energy crisis on Earth, a multinational crew on the Cloverfield Station test the Shepard particle accelerator in an attempt to produce clean and accessible power. The crew consists of English engineer Ava Hamilton (Gugu Mbatha-Raw), American Commander Kiel (David Oyelowo), German physicist Ernst Schmidt (Daniel Brühl), Brazilian medical doctor Monk Acosta (John Ortiz), Irish engineer Mundy (Chris O'Dowd), Russian engineer Volkov (Aksel Hennie), and Chinese engineer Tam (Zhang Ziyi). Ava worries about leaving her husband Michael, especially in light of the recent loss of their children in a house fire. After several years of failed attempts, the accelerator finally works but a subsequent power surge causes a series of strange events. Volkow becomes paranoid and potentially homicidal. A woman is found fused with wires behind a bulkhead. The crew learn that she comes from an identical Cloverfield Station in another dimension. Meanwhile on earth the interdimensional crossovers result in mass destruction. Can the crew of Cloverfield Station rectify the situation?

As Paramount Pictures were so successful in adapting an original script and transforming it into a tangential sequel with 10 Cloverfield Lane, it is understandable why they elected to try this a second time. Hence another spec script, this titled God Particle, was procured and retrofitted into a third edition to the “Cloververse”. The only difference this time is that that transition is far from seamless and results in a film that looks like it has been clearly assembled from separate elements. Many of the plot devices in The Cloverfield Paradox just don’t hang well together. The screenplay focuses on the particle accelerator experiments tearing the fabric of space time and opening portals to multiple parallel universes. Because these incursions can occur at any point in Earth’s timeline, this provides a convenient means to explain both previous sequels. Hence we have a Kaiju attack in 2008 and an alien invasion in 2016. But other elements of the story remain woefully underdeveloped. Michael Hamilton’s rescue of a young girl offers an opportunity to explore his own loss of his children. It is however neglected. The backstory and dynamics of the crew on the Cloverfield Space Station is also very thin.

Director Julius Onah does not manage to pull the elements together cohesively and so The Cloverfield Paradox often feels like a series of clever but ever so contrived CGI set pieces, linked by some clumsy and at times dull plot exposition. What makes it all the more frustrating is that there are some good ideas here and with more care and attention to the screenplay, this could have been a far better film. The final scene pretty much highlights everything that is wrong in the film, as it crassly crowbars in a reference to Cloverfield that couldn’t have been any less subtle if it tried. However, budget overruns and a lack of confidence in the finished product saw Paramount Pictures sell The Cloverfield Paradox to Netflix, rather than risk a theatrical release. Which means that this odd and vicarious trilogy of films, which grew into a franchise out of purely financial reasons, has more than likely run its course.

As Above, So Below (2014)

The found footage genre is predicated on the concept that the material the audience watches is supposed to be filmed from real life. This therefore presents a challenge for actors as their performances have to appear like everyday social interactions. Most people are not great orators with extensive vocabularies, in real life. Watch any wedding video or vox pop on a news broadcast and you’ll quickly become aware of the gulf between how people express themselves in reality and the stylised, contrived manner in which actors deliver dialogue. Hence, during the first act of As Above, So Below I became aware that the cast were “acting”. They were using dramatic techniques commonly used in conventional film but which stands out far more in this genre. This changed as the film progressed and the story became more deliberately chaotic. But it was noticeable during the initial set up to the story. It’s not something I’ve noticed before with other found footage movies. But in many ways, As Above, So Below is quite different compared to other genre examples

The found footage genre is predicated on the concept that the material the audience watches is supposed to be filmed from real life. This therefore presents a challenge for actors as their performances have to appear like everyday social interactions. Most people are not great orators with extensive vocabularies, in real life. Watch any wedding video or vox pop on a news broadcast and you’ll quickly become aware of the gulf between how people express themselves in reality and the stylised, contrived manner in which actors deliver dialogue. Hence, during the first act of As Above, So Below I became aware that the cast were “acting”. They were using dramatic techniques commonly used in conventional film but which stands out far more in this genre. This changed as the film progressed and the story became more deliberately chaotic. But it was noticeable during the initial set up to the story. It’s not something I’ve noticed before with other found footage movies. But in many ways, As Above, So Below is quite different compared to other genre examples

Archaeologist Scarlett Marlowe (Perdita Weeks) is obsessed with finding Nicholas Flamel's alchemical Philosopher's Stone. After finding an inscription in a cave in Iran, written in Aramaic, she travels to Paris along with her documentary cameraman Benji (Edwin Hodge). She meets with her former boyfriend George (Ben Feldman) who is an expert in ancient languages. After deciphering the inscription and using it to find hidden information on the back of Nicholas Flamel's gravestone, they discover that the Philosopher's Stone is located in the Parisian Catacombs. The team then finds a group of unofficial guides, Papillon, Siouxie and Zed, who are experienced exploring the parts of the Catacombs not open to the public. They enter the subterranean necropolis and when a tunnel collapses, are forced to take a route that has previously not been explored. Papillon is nervous as a close friend of his La Taupe vanished here, despite his knowledge. As the group travel further they become aware that all is not as it seems and that they’re all being haunted by their own past.

Once the cast are trapped in the Parisian Catacombs the plot draws heavily from Dante's Inferno. Given the scope of the story and the nature of themes therein, I would argue that maybe it would have been preferable to have made As Above, So Below a standard horror film, rather than in the found footage format. However, writers Paco Plaza, Luis A. Berdejo and Jaume Balagueró certainly are innovative with regards to pushing the boundaries of this genre. There are several noticeable scenes which have a palpable sense of claustrophobia that I’ve only seen previously in The Borderlands (2013) and The Descent (2005). The characters are at times somewhat annoying with their bickering and squabbling but that is a reflection of their personalities. There is a tipping point in the story where events veer from the strange into the pure eldritch. Stone faces appear in the walls and attack people, hooded figures charge at the unwary and the narrow corridors of the necropolis fill with blood. By this point the viewer either goes with the proceedings or emotionally checks out.

Most found footage films do not hold up to close scrutiny. The most common criticism is that there often comes a point in the story where most people would stop filming and run. And this argument can certainly be levelled at As Above, So Below. However, because the story is so ambitious with its use of nonlinear time, visions of hell and exploration of alchemy, it seems pedantic to focus on minor contradictions of the format and the film’s own internal logic. There’s also an off kilter ambience to the proceedings. Simple things like finding a piano amid the dust and confines of the tunnel are disquieting. Papillon coming across one of his own graffiti tags which he claims he hasn’t done is similarly bothersome. Plus the Parisian Catacombs themselves are just plain sinister. I suspect there may be no middle ground with As Above, So Below. You’ll either embrace its ambition and enjoy it or dismiss it out right. I chose the former.

Telefon (1977)

When one considers all the various elements involved in the production of Telefon, it makes it all the more disappointing that the movie fails to reach its potential. The basic idea about sleeper agents in the US is sound but the story doesn’t really go anywhere and not a great deal happens. The strong cast featuring Charles Bronson, Lee Remick and Donald Pleasance have to do their best with an undeveloped screenplay. Considering that it was written by Peter Hyams and Stirling Silliphant (from a novel by Walter Wager) it is quite surprising how lacklustre it all is. But perhaps the most saddening aspect of the film is the somewhat indifferent direction from Don Siegel, who by his own admission was not especially engaged with the story. Considering that he had scored a major hit the previous year with John Wayne’s swansong The Shootist, makes it more curious that he wasn’t more enthused. Even Lalo Schifrin’s score fails to bolster Telefon.

When one considers all the various elements involved in the production of Telefon, it makes it all the more disappointing that the movie fails to reach its potential. The basic idea about sleeper agents in the US is sound but the story doesn’t really go anywhere and not a great deal happens. The strong cast featuring Charles Bronson, Lee Remick and Donald Pleasance have to do their best with an undeveloped screenplay. Considering that it was written by Peter Hyams and Stirling Silliphant (from a novel by Walter Wager) it is quite surprising how lacklustre it all is. But perhaps the most saddening aspect of the film is the somewhat indifferent direction from Don Siegel, who by his own admission was not especially engaged with the story. Considering that he had scored a major hit the previous year with John Wayne’s swansong The Shootist, makes it more curious that he wasn’t more enthused. Even Lalo Schifrin’s score fails to bolster Telefon.

As the Cold War gives way to détente, the Soviet government purges old Stalin loyalists that do not favour peace. Nikolai Dalchimsky (Donald Pleasence), a rogue KGB member, flees to America, taking with him a document which contains details of obsolete sleeper agents. As he begins activating them, American counterintelligence is baffled by random acts of terrorism, committed by ordinary citizens against what were formerly top secret facilities. To prevent a war that neither side wants, KGB Major Grigori Borzov (Charles Bronson) is sent to neutralise Dalchimsky. Borzov has a photographic memory and hence retains all the information from the copy of the “telefon book” that Dalchimsky has taken. On arrival in the US, Borzov is assisted by longterm agent Barbara (Lee Remick). Together they seek a pattern to which agents that Dalchimsky is activating. Will they be able to stop him in time, while avoiding the US authorities.

The rights for the novel Telefon were acquired by MGM in late 1974 and the studio were confident that it would make a marketable thriller. Peter Hyams wrote the first draft of the screenplay and was hoping to direct the film himself. However, as his previous project for MGM, Peepers, had failed at the box office, he quickly realised that an alternative director would be assigned the job. So he wrote a second draft of the script for Richard Lester. However, Lester left the project and Don Siegel replaced him. The veteran director was mainly interested in working with Charles Bronson again and was not enamoured with Hyams work. So Stirling Silliphant wrote a third revision of the screenplay. The production then began filming in Finland which doubled for Russia, before returning to the US. The explosive set pieces and stunts were handled by Paul Baxley. Sadly, beyond the initial excitement of working with Bronson, Siegel found that the story didn’t “make much sense” and did not apply himself as diligently to his work as he had in previous years.

Telefon is clearly lacking in substance and does have a somewhat perfunctory quality to it. Yet there are some good ideas present and it offers at first glance a variation on themes seen previously in The Manchurian Candidate. Lee Remick is quirky, with a dry sense of humour. Bronson easily fills the role as a KGB Major. But there’s a lack of urgency to the screenplay and it feels too much like a TV movie from this era, albeit one with a bigger budget. Perhaps the film’s biggest mistake is it’s need to have a “happy ending”, as opposed to a more credible one. And as you’d expect from a production with such a history of change and artistic indifference, the press were equally ambivalent. Some critics accused the film of being anti peace. Others felt that Telefon was too pro Russian. Similarly, the film failed to find a consensus among cinema goers. Perhaps if Peter Hyams had directed his own first draft of the script, we may well have had a superior film. However, after departing Telefon, Hyams went onto write and direct Capricorn One, so one can argue that every cloud has a silver lining.

Tales That Witness Madness (1973)

I have a soft spot for portmanteau horror films, especially those made in the UK during the seventies. They often have an impressive cast of character actors and offer a snapshot of fashion, culture and sensibilities from the times. However, their weakness often lies with the inconsistency of the various stories. These can range from the outstanding, to what can best be described as filler. Furthermore, although the latter category have just as short a running time as the other vignettes, it is always the poor ones that seem to drag and disrupt the flow of the film. Tales That Witness Madness does not suffer too badly from this problem. Out of the four stories that are featured two stand out and two others are just average and not overtly bad. However, irrespective of potential narrative inconsistencies, there are some good ideas and a ghoulish streak running throughout the fill’s ninety minute running time.

I have a soft spot for portmanteau horror films, especially those made in the UK during the seventies. They often have an impressive cast of character actors and offer a snapshot of fashion, culture and sensibilities from the times. However, their weakness often lies with the inconsistency of the various stories. These can range from the outstanding, to what can best be described as filler. Furthermore, although the latter category have just as short a running time as the other vignettes, it is always the poor ones that seem to drag and disrupt the flow of the film. Tales That Witness Madness does not suffer too badly from this problem. Out of the four stories that are featured two stand out and two others are just average and not overtly bad. However, irrespective of potential narrative inconsistencies, there are some good ideas and a ghoulish streak running throughout the fill’s ninety minute running time.

Tales That Witness Madness is not an Amicus production but instead made by World Film Services. Efficiently directed by Freddie Francis, the framing story set in a high security psychiatric hospital sets an interesting tone. It is a brightly lit, modern environment and a far cry from the typical gothic asylums that are de rigueur in the horror genre. Jack Hawkins (dubbed by Charles Gray) and Donald Pleasance effortlessly navigate through their respective roles as two Doctors discussing cases. The first story, “Mr.Tiger”, is by far the weakest and is no more than the sum of its parts. A young boy has an imaginary friend who happens to be a tiger. It subsequently kills his parents who are constantly bickering. No explanation or deeper motive is provided. The second tale, “Penny Farthing”, packs a lot more into its duration including time travel, murder and a fiery denouement. It doesn’t make a lot of sense when thought about but it is a creepy vignette.

“Mel” is by far the oddest and most interesting story on offer. While out running Brian (Michael Jayston) finds a curious tree that has been cut down. He brings it home and places it in his lounge, much to his wife Bella’s annoyance (Joan Collins). Fascinated by the tree, which has the name Mel carved into it, he lavishes it with attention. Bella becomes jealous and decides to get rid of her rival. Naturally the story has a twist. There’s also a lurid dream sequence featuring Mel attacking Bella that predates The Evil Dead. The final story “Luau” about Auriol Pageant (Kim Novak) whose new client Kimo (Michael Petrovich) has designs on her daughter Ginny (Mary Tamm) is formulaic. The finale featuring a feast to appease a Hawaiian god is somewhat obvious. The climax of the framing story is also somewhat perfunctory but it does neatly conclude the proceedings.

The portmanteau horror sub genre has on occasions surpassed itself with such films as Dead of Night and Creepshow. But the inherent risk of providing a “visual buffet”, is that like the culinary equivalent, they’ll always be something you don’t like or that has been added because it’s cheap and easy. There is an element of this in Tales That Witness Madness. However, when reflecting upon not only British horror films from the seventies but other genres as well, one must remember that cinema was still a major source of entertainment and that a lot of the material was quickly produced to fill gaps in the market that TV could not provide at the time. With this in mind, Tales That Witness Madness may not be especially entertaining to the casual viewer. The more dedicated horror fan may find it more entertaining and of interest as an example of a specific sub genre that has fallen into decline in recent years.

Wake Wood (2009)

Sometimes when making a film, less can indeed be more. Practical things like keeping the scope of your story simple, working within your budget and not feeling obliged to justify or explain every aspect of the plot can prove invaluable. If you can do all of these things with a robust cast, intelligent direction, while maintaining your viewers attention, then you have achieved something that many studios and independent filmmakers usually cannot do. Director David Keating has managed to do this with the 2009 horror film Wake Wood. Along with Brendan McCarthy who he co-wrote the screenplay with him, Wake Wood efficiently and charismatically tells its tale. It is well paced, with relatable characters and good performances. The atmosphere builds and there are some jolting moments of horror. Furthermore, it is both unusual and rewarding to see pagan rituals portrayed as an extension of rural life, in the same way as farming and animal husbandry. It is neither malevolent or benign but just an ever present force.

Sometimes when making a film, less can indeed be more. Practical things like keeping the scope of your story simple, working within your budget and not feeling obliged to justify or explain every aspect of the plot can prove invaluable. If you can do all of these things with a robust cast, intelligent direction, while maintaining your viewers attention, then you have achieved something that many studios and independent filmmakers usually cannot do. Director David Keating has managed to do this with the 2009 horror film Wake Wood. Along with Brendan McCarthy who he co-wrote the screenplay with him, Wake Wood efficiently and charismatically tells its tale. It is well paced, with relatable characters and good performances. The atmosphere builds and there are some jolting moments of horror. Furthermore, it is both unusual and rewarding to see pagan rituals portrayed as an extension of rural life, in the same way as farming and animal husbandry. It is neither malevolent or benign but just an ever present force.

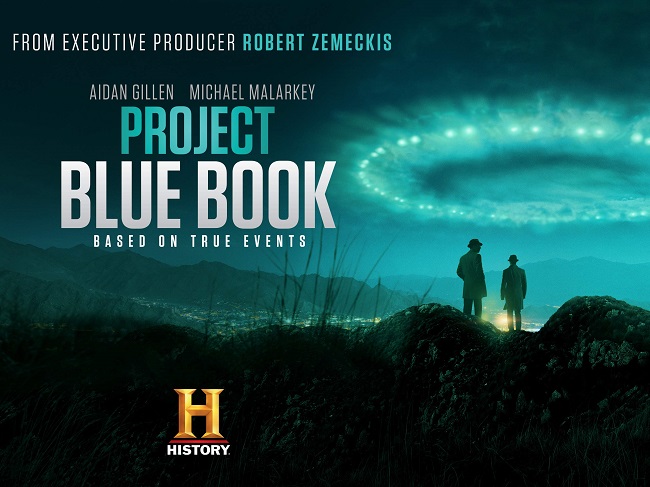

Vet Patrick Daley (Aiden Gillen) and his wife Louise (Eva Birthistle), a pharmacist, move to the rural village called Wake Wood, after their daughter Alice (Ella Connolly) is mauled to death by a dog. Louise struggles to come to terms with her loss and the fact she can have no further children. One evening after their car breaks down, Patrick and Louise go to the nearby house of Patrick's veterinary colleague, Arthur (Timothy Spall), for assistance. Louise witnesses Arthur conducting a pagan ritual but says nothing to Patrick. Lousie becomes increasingly aware that something is not quite right with the village and that Arthur saw her observing the ritual. Soon afterwards a farmer is killed by his own bull while Patrick is tending to it. Horrified by another accidental death the couple plan to leave, but Arthur convinces them to stay. He claims he can bring their daughter back but only for three days and only if she has been dead for less than a year. The conflicted couple agree to his offer on the understanding that they must remain in Wake Wood forever.

If you are familiar with The Wicker Man, Don’t Look Now or any of the adaptations of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary then you’ll find several similar themes present in Wake Wood. This is a film about loss, how people cope with bereavement and what personal sacrifices you would make just to see your loved one again. Fortunately for such a character driven story, performances are universally good. Aiden Gillen is very plausible as a man throwing himself into his work to avoid his feelings. Eva Birthistle excels as a Mother who cannot move on after the death of her only child. Timothy Spall compliments the cast as retired veterinarian Arthur. He brings an air of normalcy to the pagan elements of the plot and his performance is quietly understated rather than overtly theatrical.The Irish setting and cultural heritage gives a uniquely Celtic feel to the proceedings and provides sufficient difference from other genre movies that have trodden a similar path. Overall, Wake Watch does not overreach itself and contains some rather flamboyant Fulci-eque violence to boot. Hence it is a superior genre movie. Competitors should take note.

The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959)

The stories of Hammer films “horsetrading” with the British Board of Film Censorship (as the BBFC were called at the time) make for some interesting reading. If you're interested in the history of the studio I thoroughly recommend the book A New Heritage of Horror: The English Gothic Cinema by David Pirie. However, the BBFC felt that they’d been hoodwinked after the release of The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957, which had managed to smuggle additional unpleasantries into the final theatrical edit. Henceforth the board took a more formidable stance when dealing with Hammer and all subsequent releases. Hence The Man Who Could Cheat Death feels somewhat tame compared to earlier Hammer films. Although cuts were made to the final edit of the movie, one gets the impression that maybe the more salacious and graphic content was possibly reduced when writing the screenplay. However, with that all said, The Man Who Could Cheat Death is still a handsome, performance driven Hammer horror.

The stories of Hammer films “horsetrading” with the British Board of Film Censorship (as the BBFC were called at the time) make for some interesting reading. If you're interested in the history of the studio I thoroughly recommend the book A New Heritage of Horror: The English Gothic Cinema by David Pirie. However, the BBFC felt that they’d been hoodwinked after the release of The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957, which had managed to smuggle additional unpleasantries into the final theatrical edit. Henceforth the board took a more formidable stance when dealing with Hammer and all subsequent releases. Hence The Man Who Could Cheat Death feels somewhat tame compared to earlier Hammer films. Although cuts were made to the final edit of the movie, one gets the impression that maybe the more salacious and graphic content was possibly reduced when writing the screenplay. However, with that all said, The Man Who Could Cheat Death is still a handsome, performance driven Hammer horror.

In 1890, Dr. Georges Bonnet (Anton Diffring) is the talk of the Parisian art scene due to his lifelike sculptures and his ongoing affair with his model Margo Philippe (Delphi Lawrence). At a party to unveil his latest work, Bonnet meets Dr. Pierre Gerrard (Christopher Lee) and his companion Janine Du Bois (Hazel Court). Janine had a torrid romance with Dr. Bonnet ten years ago in Italy. Against his better judgement Bonnet resumes his affair with Janine, although he refuses to explain why he vanished a decade prior. In the meantime, Bonnet awaits the arrival of his lifelong friend, Dr. Ludwig Weiss (Arnold Marlé) from Switzerland. Weiss is a pioneer in his medical field and Bonner is dependent upon him to perform a unique operation that he needs to stay alive. However, when Weiss finally arrives he has suffered a stroke and can no longer use his right hand. Perhaps Dr. Gerrard can be persuaded to perform the procedure. However, matters are further complicated not only by the love triangle between Bonner, Janine and Gerrard but by a visit from Inspector Legriss (Franics De Wolff), who is investigating the sudden disappearance of Margo Phillippe.

The Man Who Could Cheat Death is a typical Hammer production in so far as it is studio based with little or no exterior shots. The sets are suitably atmospheric and gothic, though some were redressed from the previous production, The Hound of the Baskervilles. Cinematographer Jack Asher used pastel coloured filters when lighting the more sinister scenes, especially when Dr. Bonnet is in his laboratory, drinking his elixir or suffering the ill effects of his medical condition. As ever with Hammer films, the lead cast do much to carry the plot and distract the viewer from the shortcomings of the screenplay. Sadly, as mentioned previously, the horror content is rather light in this film. Several murders happen either offscreen or with the killer blocking the audience's view. There was some additional nudity shot for the European and Asian markets but no such material made it into the UK and US release. The most ghoulish scene occurs at the film’s denouement and also features some interesting stunt work.

The Man Who Could Cheat Death is neither the best example of Hammer Film Productions output from the fifties nor the worst. Anton Diffring does well in the lead role which was originally intended for Peter Cushing. The film does not out stay its welcome with a running time of 83 minutes, although it is rather verbose with the emphasis upon narrative drama, rather than action. Naturally judged by today’s standards it is all rather tame but films such as this were causing quite a stir at the time and there was a lot of critical disdain for these lurid, technicolor horror stories. However Hammer chose to focus on the box office returns and so continued producing to a tried and tested formula. They had a knack for making their films look more sumptuous than they really were due to clever production design and inventive photography. They also new that sex sells and were not averse to focusing on the moral corruption that usually goes hand in hand with violence and horror.

The Reptile (1966)

After his brother Charles dies in mysterious circumstances, Harry Spaulding (Ray Barrett) inherits his cottage in the Clagmoor Heath, Cornwall. He quickly moves in with his new bride, Valerie (Jenifer Daniel), with a view to finding out what happened. However, he is shunned by the locals apart from the village publican, Tom Bailey (Michael Ripper), who befriends him. The only other resident in the vicinity of the cottage is Dr. Franklyn (Noel Willman), the owner of the nearby Well House. He lives with his daughter Anna (Jacqueline Pearce), who is attended by a silent Malay servant (Marne Maitland). Anna is a strange girl who seems to be harbouring a secret. Her father treats her contemptuously and does his utmost to keep her confined to Well House. When the local village eccentric, Mad Peter (John Laurie), dies in a similar fashion to Charles Spaulding, both Harry and Tom decide to take matters into their own hands and to investigate further.

After his brother Charles dies in mysterious circumstances, Harry Spaulding (Ray Barrett) inherits his cottage in the Clagmoor Heath, Cornwall. He quickly moves in with his new bride, Valerie (Jenifer Daniel), with a view to finding out what happened. However, he is shunned by the locals apart from the village publican, Tom Bailey (Michael Ripper), who befriends him. The only other resident in the vicinity of the cottage is Dr. Franklyn (Noel Willman), the owner of the nearby Well House. He lives with his daughter Anna (Jacqueline Pearce), who is attended by a silent Malay servant (Marne Maitland). Anna is a strange girl who seems to be harbouring a secret. Her father treats her contemptuously and does his utmost to keep her confined to Well House. When the local village eccentric, Mad Peter (John Laurie), dies in a similar fashion to Charles Spaulding, both Harry and Tom decide to take matters into their own hands and to investigate further.

Filmed simultaneously with The Plague of Zombies with which it shared several sets, The reptile is a slower paced, more thoughtful film that prefers to focus on the psychological collapse of its central characters, rather than set pieces. It is one of the best Hammer movies from the sixties which blends traditional horror elements with more mainstream period costume dramas. The production design is stylish and captures the atmosphere of a claustrophobic Cornish village. The interiors of Well House are an interesting juxtaposition to this, with Dr. Franklyn’s exotic flowers and penchant for Indian culture. As for the Reptile makeup by Roy Ashton, it works well by the standards of the time. Director John Gilling wisely keeps scenes featuring the transformed Anna, to a minimum and lights them favourably. Another ghoulish embellishment is the way the victims turn black and purple after being bitten.

However, it is the central performance by Jaqueline Pearce which is the standout feature of The Reptile. She gives a haunting performance often relying purely on her demeanour, rather than dialogue to express her torment. Noel Willman, who was a substitute for Peter Cushing, is also notable as Anna’s guilt wracked father. He is the architect of both his own and his daughter’s ruin while also being a victim of her curse. Another enjoyable aspect of The Reptile is seeing Hammer stalwart Michael Ripper in an expanded role and not meeting a grisly demise. Sadly, some cuts originally made to the film by the BBFC for its theatrical release, still persist and the material has not been found or restored to the current Blu-ray release. Yet The Reptile remains a superior example of Hammer’s work from this era, before they felt compelled to make their content more salacious to stay competitive.

Slayground (1983)

There have been several movie adaptations of the books of Jonathan Stark (AKA Donald E. Westlake) featuring his career criminal lead character, Parker. Sadly not all of them have fared well, either critically or at the box office. Many have deviated from the source material, often just using mere aspects of the original plot as the basis of their screenplay. Perhaps the most successful of these has been Point Blank (1967), directed by John Boorman and starring Lee Marvin. Slayground sadly follows the pattern set by previous adaptations. It changes several character names and takes two main elements from the source text and uses them as a premise. Specifically, a robbery that goes wrong which results in an accidental death and a climactic shootout in an out of season fairground. Due to the financing of the film, half of the story takes place in the US and the other in the UK. Much of the cast are British, resulting in a curious and at first glance somewhat incongruous film.

There have been several movie adaptations of the books of Jonathan Stark (AKA Donald E. Westlake) featuring his career criminal lead character, Parker. Sadly not all of them have fared well, either critically or at the box office. Many have deviated from the source material, often just using mere aspects of the original plot as the basis of their screenplay. Perhaps the most successful of these has been Point Blank (1967), directed by John Boorman and starring Lee Marvin. Slayground sadly follows the pattern set by previous adaptations. It changes several character names and takes two main elements from the source text and uses them as a premise. Specifically, a robbery that goes wrong which results in an accidental death and a climactic shootout in an out of season fairground. Due to the financing of the film, half of the story takes place in the US and the other in the UK. Much of the cast are British, resulting in a curious and at first glance somewhat incongruous film.

Long term thief Stone (Peter Coyote) and his accomplice Joe Sheer (Bill Luhrs) arrive in a rundown part of New York State to rob an armoured car. When their usual driver Laufman fails to join them, Sheer employs local driver Lonzini (Ned Eisenberg). Despite successfully undertaking their robbery, Lonzini collides with another car while making their getaway. When Stone investigates the wreckage he discovers all passengers are dead including a young girl. Shocked and outraged by this needless tragedy, Stone threatens to kill Lonzini, however, Sheer intervenes and the gang go their separate ways. But the Father of the dead girl (Michael M. Ryan), a wealthy sports businessman, hires charismatic assassin Costello (Phillip Sayer) and instructs him to find all involved in her death and to kill them. Stone soon learns that he is a marked man, when Lonzini is found brutally murdered. He flees to the UK and seeks out former associate Terry Abbatt (Mel Smith), in the hope of lying low and avoiding the price on his head. But Costello is tenacious and pursues him, relentlessly killing all in his path.

Slayground was written and adapted by British screenwriter Trevor Preston, a veteran of such British cop shows as The Sweeney. Hence several scenes reflect his customary gritty and hard boiled dialogue. The movie starts in a run down part of the US and then relocates to a comparably run down part of the UK. This narrative continuity may well have had a greater significance initially. But Slayground feels like a film that may have substantially re-edited prior to release. It runs for a tight 89 minutes and doesn’t waste it’s time on niceties or unnecessary embellishments. The direction by former cameraman Terry Bedford is uncomplicated and reflects the down-at-heel lifestyle and world of the main characters.

Yet there are major narrative gaps in the proceedings. Where Walter Hill wrote deliberately minimalist characters for The Driver, the flow of events in Slayground gives one the distinct impression that there is 10 to 15 minutes of expositional material is missing. Furthermore, the hitman Costello has a penchant for arranging the bodies of his victims. Yet these scenes are brief and their actual death sequences are conspicuously absent.

Hence the cast are left with precious little to do. Stone is no more of an archetype, rather than a fully rounded character. Billie Whitlaw has only a few scenes as Madge, the owner of a financially failing amusement park, although she gets by on the strength of her personality. And Mel Smith doesn’t arrive until the film’s final act. He delivers a particularly powerful soliloquy about a criminal’s lot in life and we get a brief glimpse of his straight acting talent. But again the proceedings surge ahead towards the climactic showdown between Stone and Costello and the production seems to dismiss the gaps in the plot . What we should have experienced throughout Slayground is a man’s journey through his past as he reflects upon the lifestyle he has chosen and its consequences. Sadly we are instead taken on a journey from A to B to C, where everyone we meet becomes another corpse within minutes of being introduced.

Yet despite its multiple shortcomings, there are a few aspects of Slayground that standout. The film starts with a small vignette that shows the fate of the original getaway driver, Laufman. It is a creative opening gambit. The hitman Costello is also an enigmatic character with his fedora hat and the way we never fully get to see his face. His playful tanting of his victims is an interesting foible. The denouement in the amusement park is suitably creepy, as the fairground automatons are caught in the crossfire. But ultimately this movie fails to reach its full potential, either because of ill conceived editing designed to “streamline” the story, or because the director simply didn’t have the experience to craft a more rounded and detailed narrative. As it stands, Slayground remains a curious anomaly. One of four films produced by Thorn EMI in the early eighties under the auspices of Verity Lambert. The others being Comfort and Joy, Morons from Outer Space and Dreamchild.

White Noise (2005)

Successful writer Anna Rivers (Chandra West) goes missing prior to the launch of her new book. Shortly after, her car is found abandoned by the roadside and her body is discovered in the harbour. The Police conclude that there's been a tragic accident. Her husband, architect Jonathan Rivers (Michael Keaton), is devastated by her loss. When he is approached by Raymond Price (Ian McNeice), who claims he has recorded messages from Anna through electronic voice phenomena (EVP), Jonathan is both sceptical and angry. However, his curiosity eventually gets the better of him and he meets with Raymond and quickly becomes immersed in EVP phenomenon. As Jonathan experiments with EVP recording he begins to discern messages from the dead. However, it soon becomes apparent that these communications are of a precognitive nature and that there are more sinister forces at work.

Successful writer Anna Rivers (Chandra West) goes missing prior to the launch of her new book. Shortly after, her car is found abandoned by the roadside and her body is discovered in the harbour. The Police conclude that there's been a tragic accident. Her husband, architect Jonathan Rivers (Michael Keaton), is devastated by her loss. When he is approached by Raymond Price (Ian McNeice), who claims he has recorded messages from Anna through electronic voice phenomena (EVP), Jonathan is both sceptical and angry. However, his curiosity eventually gets the better of him and he meets with Raymond and quickly becomes immersed in EVP phenomenon. As Jonathan experiments with EVP recording he begins to discern messages from the dead. However, it soon becomes apparent that these communications are of a precognitive nature and that there are more sinister forces at work.

White Noise is a slick and glossy production, sporting a modern clean aesthetic that reflects the world of its central character. Much of the story takes place in Jonathan’s home which is a brightly lit, glass palace. The visual style along with the use of what was contemporary technology effectively juxtapose the arcane nature of the supernatural. In this film the shadowy forms of the dead appear on TV screens and monitors, instead of dimly lit corridors. It’s an interesting divergence from typical ghost story tropes but it alone cannot sustain the story. Pretty much everything else about White Noise is formulaic and predictable. That’s not to say that the production is poorly constructed. Director Geoffrey Sax keeps proceedings on track and the story doesn’t out stay its welcome. It’s just that there’s very little that’s different on offer. Keaton and the rest of the cast rely on their acting personas to keep the audience engaged, as all characters are not especially well defined.

It is not easy to quickly and efficiently establish a loving relationship in the first act of a film, and make it seem natural. It requires subtle writing and a talent for focusing on the little things that we share daily with our loved one, to imbue such scenes with a sense of credibility. You’ll find it in Poltergeist (1982) and its depiction of the Freeling family. In White Noise, the opening scenes that try and convey the love between Anne and Jonathan just seem contrived and perfunctory. Hollywood’s predilection for alway making successful, white, middle class men the protagonist in most films, is also an impediment when it comes to generating emotional investment. Beyond the superficial, IE a man who is grieving, it is not difficult to warm to Jonathan Rivers. He’s not a bad man, just a bland one. The way he sidelines his young son due to his growing obsession is hardly endearing either.

Fifteen years on, despite its visual style, White Noise already seems somewhat dated. The continual advance of technology being every film’s Achilles’ heel. It’s quite nostalgic to return to a world filled with CRT TVs and monitors, MiniDiscs, Nokia phones, audio cassettes and VHS tapes. But beyond this minor appeal, the film is underdeveloped and lacking in distinguishing attributes. The story as it is, would be better suited as an episode of The Twilight Zone. The scares are mainly of the “quiet, quiet, loud” variety and any unpleasantness falls squarely into the shallow end of the PG-13 rating. If you want a straight forward, uncomplicated, horror-lite supernatural tale, then White Noise may well scratch that itch. But for genre enthusiasts, this is a somewhat indifferent film, which is possibly a bigger failing than being a bad one.

The McPherson Tape (1989)

In many ways the story behind The McPherson Tape is a lot more interesting than the film itself. This early found footage movie from 1989, was shot on home video on a virtually non-existent budget. The director Dean Alioto eventually found a distributor but on the eve of the movie’s home video release, the warehouse burned down and allegedly destroyed the master tape and all the promotional artwork. Yet this was not the end of the story. It was common practice in the eighties for small distributors to send advance copies to local independent video stores. Hence The McPherson Tape found its way into the pirate video ecosystem. It then migrated to the UFO community where it was circulated as being a video of a legitimate alien abduction. Dean found himself in the unusual position of having to debunk his own work. Three decades later due to the intriguing tale associated with The McPherson Tape, it has been remastered from the newly rediscovered 3/4" tape and re-released.

In many ways the story behind The McPherson Tape is a lot more interesting than the film itself. This early found footage movie from 1989, was shot on home video on a virtually non-existent budget. The director Dean Alioto eventually found a distributor but on the eve of the movie’s home video release, the warehouse burned down and allegedly destroyed the master tape and all the promotional artwork. Yet this was not the end of the story. It was common practice in the eighties for small distributors to send advance copies to local independent video stores. Hence The McPherson Tape found its way into the pirate video ecosystem. It then migrated to the UFO community where it was circulated as being a video of a legitimate alien abduction. Dean found himself in the unusual position of having to debunk his own work. Three decades later due to the intriguing tale associated with The McPherson Tape, it has been remastered from the newly rediscovered 3/4" tape and re-released.

On the evening of October 8, 1983, the Van Heese family gather in the Connecticut mountains to celebrate the birthday of 5-year-old Michelle. The family consists of Ma Van Heese (Shirly McCalla), her three sons Eric (Tommy Giavocchini), Jason (Patrick Kelley), and Michael (Dean Alioto), Eric’s wife Jamie (Christine Staples), his daughter Michelle (Laura Tomas) and Jason’s girlfriend Renee (Stacey Shulman). Michael uses his hand-held camera to record the night’s events, much to the amusement and irritation of his family. They chat and argue as families do as the evening progresses. However when a circuit breaker trips the brothers go outside to restore power. An unusual red light overhead arouses their curiosity so they walk to a neighbouring property, only to find a spacecraft has landed. They flee back to their own house when they are noticed by the extraterrestrial occupants. Armed with shotguns they nervously await pursuit. When something tries to enter via a window, Eric shoots it and brings the body into the house as “evidence”. Is this the end of the siege or do further perils await them?

There is the germ of a good idea in The McPherson Tape and first time writer and director Dean Alioto should be applauded for trying to do something so unusual and ambitious like this back in 1989, when this genre was still in its infancy. But the film struggles to sustain its relatively short hour running time. Despite all the logical concessions that you can make to both the production and cast, this is a ponderous undertaking and a tough watch. It genuinely does at times come across as exactly watching someone’s home videos. Despite restoration, the picture quality is poor however that does work in the films favour to a degree. The characters act in a relatively plausible fashion, arguing among themselves and generally acting impulsively and without any critical thinking. But events take too long to go anywhere and by the time we reach a point where things start to get “interesting” the film ends because it has achieved its purpose.

Hence, I cannot recommend The McPherson Tape to the casual viewer, as it doesn’t really meet mainstream entertainment standards. This is most definitely a niche market product that will best suit the genre completist and aficionado. The editing is minimal and cleverly disguised making The McPherson Tape look very much like a continuous piece of footage. The camera at times is out of focus or points at a plate or the floor. Keeping things simple in scope certainly helps the proceedings and therefore we only see a small amount of the UFO and the aliens themselves. The commentary track on the new Blu-ray release is by far the biggest selling point and it is fascinating to learn how a small budget film ended up fuelling alien abduction conspiracy theories. The director later went on to remake the film with a larger budget and studio backing in 1998, under the title Alien Abduction: Incident in Lake County.

I, Monster (1971)

I, Monster is a low budget Amicus production and a cunning retelling of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde”. Due to copyright reasons, these names are not used in the film and are replaced with new characters, Marlowe and Blake respectively. However, despite the modest budget and the aforementioned legal issues, this is a very faithful adaptation of the original gothic novella. Milton Subotsky’s screenplay incorporates all the essential elements of the source text which is both a boon and a bane. A boon because it really does capture the essence of Stevenson’s concept, which has been drastically misrepresented by previous adaptations. And a bane in so far that the original novella is a little too insubstantial to sustain a feature film. Even at a modest 75 minutes running time I, Monster feels somewhat “thin”.

I, Monster is a low budget Amicus production and a cunning retelling of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde”. Due to copyright reasons, these names are not used in the film and are replaced with new characters, Marlowe and Blake respectively. However, despite the modest budget and the aforementioned legal issues, this is a very faithful adaptation of the original gothic novella. Milton Subotsky’s screenplay incorporates all the essential elements of the source text which is both a boon and a bane. A boon because it really does capture the essence of Stevenson’s concept, which has been drastically misrepresented by previous adaptations. And a bane in so far that the original novella is a little too insubstantial to sustain a feature film. Even at a modest 75 minutes running time I, Monster feels somewhat “thin”.

Psychologist Charles Marlowe (Christopher Lee), a strong advocate of Sigmund Freud, argues about man’s capacity for evil with his colleagues at his Gentlemen’s club. Dr. Lanyon (Richard Hurndall) refutes his assertions on medical grounds. Enfield (Mike Raven) reflects on a life based upon self gratification. Utterson (Peter Cushing), Marlowe’s Lawyer argues that human civilisation is based upon governing our passions. But Marlowe feels that research in this field could reduce patient’s inhibitions, which are often the root cause of their problems. He subsequently uses a drug he has created on two of his patients. It seems to either make the subject docile or facilitate their secret urges. As he ethically cannot risk any further tests, he takes the drug himself, releasing his alter ego Edward Blake. At first Blake is content with the most obvious worldly pleasures but over time he becomes more violent and uncontrollable. Marlowe’s friends are unaware of his experiments and fear that Blake is simply a ruffian that is blackmailing the doctor.

I, Monster is a somewhat set bound production with a few locations scenes. As the screenplay is true to the novella, a lot of Blake’s crimes are discussed retrospectively by the main cast and not shown on screen. There is a knife fight and a chase scene that culminates in a murder but overall, the film is some what light on unpleasantries for a horror film. It isn’t especially long either which is another issue. However, Christopher Lee’s performance is compelling and does much to mitigate the production’s shortcomings. Unlike other film adaptations there are no overly theatrical transformation scenes. When Lee initially “releases” his alter ego, we simply see his stern Victorian demeanour relax into a rather sinister and lascivious smile. Over time Blake’s features become coarser. His rictus smile is like that of a slavering beast and his complexion reflects his debauched lifestyle. Simple make-up is effectively used to reinforce Lee’s physical performance.

The rest of the cast provide robust support, with Peter Cushing as ever bringing dignity, gravitas and conviction to his modest role. There is a simple fight scene at the end of the film which takes place within a small room. Filmed through the exterior windows, it does “quite a lot with very little” and works well. It makes the conflict between Utterson and Blake very personal. This is where the film’s budget provides some creativity and innovation. Sadly, despite practical cinematography by Moray Grant, the film has an unpleasant colour palette with an emphasis on greens and yellow. This may be due to a 3D process that was originally intended but subsequently abandoned prior to release. Ultimately I, Monster did not perform well at the box office. Its brevity and lack of scope couldn’t compete with bigger budget, more contemporary horror movies that were replacing the gothic genre. However, the film has seen a critical reassessment in recent years, mainly due to Lee’s strong performance.

I Walked With a Zombie (1943)

Until today, I have never seen the iconic horror movie, I walked With a Zombie. Some classic titles just seem to fall through your “movie net”, as it were. However, BBC iPlayer has a selection of RKO films available to watch for free (sadly, only for UK viewers), so as I had a convenient gap in my schedule, I finally caught up with this seminal title today. As expected it was visually an utter delight. Other aspects of the movie are more subtle and require some reflection to determine their virtue. The lurid title, doesn’t in any way do the film justice and was forced upon the production by studio executives. Essentially this is a romantic drama fused with the supernatural and set in an exotic location. The Caribbean setting and culture along with the voodoo element add an undercurrent of sexual tension to the central love, cleverly augmenting what is essentially a gothic tale by placing it in an alien setting.

Until today, I have never seen the iconic horror movie, I walked With a Zombie. Some classic titles just seem to fall through your “movie net”, as it were. However, BBC iPlayer has a selection of RKO films available to watch for free (sadly, only for UK viewers), so as I had a convenient gap in my schedule, I finally caught up with this seminal title today. As expected it was visually an utter delight. Other aspects of the movie are more subtle and require some reflection to determine their virtue. The lurid title, doesn’t in any way do the film justice and was forced upon the production by studio executives. Essentially this is a romantic drama fused with the supernatural and set in an exotic location. The Caribbean setting and culture along with the voodoo element add an undercurrent of sexual tension to the central love, cleverly augmenting what is essentially a gothic tale by placing it in an alien setting.

Betsy Connell (Frances Dee), a young Canadian nurse travels to an island in the West Indies to care for Jessica Holland (Christine Gordon), the wife of plantation manager Paul Holland (Tom Conway). Jessica has been diagnosed by Dr Maxwell (James Bell) as suffering from a form of mental paralysis as a result of tropical fever. Betsy finds Paul Holland aloof and dour, yet strangely compelling. Wesley Rand (James Ellison), the plantation overseer and Paul’s half brother implies that Jessica’s condition is due to something Paul has done. Mrs Rand (Edith Barrett), mother to both sons, befriends Jessica. She runs the local pharmacy and has a deep understanding of local customs. Betsy suspects she may well know more than she says regarding the enmity between Wesley and Paul and the reason for Jessica’s condition. Eventually Betsy realises that modern medicine cannot provide a solution to Jessica’s malady and begins to suspect that the island’s voodoo heritage may provide an answer.

I walked With a Zombie was the second collaboration between producer Val Lewton and director Jaques Tourneur. The high concept of transposing the plot of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre to the West Indies and juxtaposing the traditional love triangle (or in this case more of a love square) with the more sensational and salacious aspects of voodoo works very well. The traditional gothic beats played out against prophetic calypso songs and pagan customs add to the atmosphere and create a subtly different supernatural experience compared to traditional Hollywood fare of the time. Director of cinematography J. Roy Hunt uses light and shade to great effect. Traditional european architecture and graveyards are replaced by heavily backlit sugar cane fields and colonial plantation houses steeped in shadows. It is a remarkably eerie environment. The highlight of the film being Betsy and Jessica’s night time journey through the canefields, as they pass voodoo talismans and animal offerings, eventually ending in their iconic meeting with the towering somnambulist Carre-Four.

Jacques Tourneur's direction creates a palpable sense of fear and the film uses its 69 minute running time most efficiently. The film does not feel the need to explain all aspects of the island’s culture and its voodoo rituals. It provides just enough details to allow a degree of ambiguity to remain. Nor does the script shy away from the iniquities of slavery and it’s lasting effect on the population. There is also an element of religious symbolism with a ship's figurehead that is fashioned to represent Saint Sabastian. Performances are acceptable, although the gender roles and period attitudes may seem “dated” to modern viewers. The film reaches a suitably melodramatic climax which concludes the story in the only credible fashion possible. However, the film uses narration from the perspective of Betsy Connell to frame the story and the closing codicil suddenly introduces a degree of previously absent moral judgment. I found this a little incongruous.

After watching I walked With a Zombie, it is clear where many of the tropes and mainstays of the horror genre come from. The movie doesn’t really offer a zombie in the modern sense, preferring to let the viewer decide if Jessica Holland is the victim of a bona fide medical condition, whether she’s been drugged and left virtually catatonic by esoteric native drugs, or if she has been truly cursed through the use of voodoo. The imperfections and character flaws of the two half brothers and their respective love for Jessica, is presented surprisingly even handedly. The moral sentiments that are espoused at the story’s climax strike me as an afterthought, forced upon the studio by the moral lobbyists of the time. Oddly, this is just another aspect of the film that makes it fascinating. If watched superficially, I walked With a Zombie offers a ghoulish love story with a supernatural subtext. But if one pays attention to detail there is a great deal of social commentary and existential angst to be found. Things seldom touched upon by contemporary horror movies.

Fandom Memories

Syp over at Bio Break leads the charge with today’s Blaugust Promptapalooza writing prompt, with this interesting question. “What is your earliest memory related to one of your core fandoms?” Please do read his thoughts on going to see Return of the Jedi upon its original release back in 1983. It is something I can certainly relate to. I’m a decade older than Syp and so I can recollect actually seeing Star Wars for the first time at my local cinema. However as that was a starting point for a specific fandom rather than an “ongoing” example, I won’t cite it here. I have even earlier recollections of going to Longleat Safari and Adventure Park and having the extra bonus of seeing the Doctor Who Exhibition which ran there from 1973 to 2003. This would have been in August 1974 and I was six at the time. I have dim recollections of all the exhibits being mainly from the Jon Pertwee era and the Daleks being the high point of my day.

Syp over at Bio Break leads the charge with today’s Blaugust Promptapalooza writing prompt, with this interesting question. “What is your earliest memory related to one of your core fandoms?” Please do read his thoughts on going to see Return of the Jedi upon its original release back in 1983. It is something I can certainly relate to. I’m a decade older than Syp and so I can recollect actually seeing Star Wars for the first time at my local cinema. However as that was a starting point for a specific fandom rather than an “ongoing” example, I won’t cite it here. I have even earlier recollections of going to Longleat Safari and Adventure Park and having the extra bonus of seeing the Doctor Who Exhibition which ran there from 1973 to 2003. This would have been in August 1974 and I was six at the time. I have dim recollections of all the exhibits being mainly from the Jon Pertwee era and the Daleks being the high point of my day.

But as the question is about “core fandoms” I think I’ll reference a more contemporary example. One that I can recollect more clearly and so provide a more specific anecdote about. So I’d like to talk about my love of the horror genre and how as I got older, became a consummate fan. I’ve recently written about how during the 80s and 90s the UK home video market endured some rather restrictive regulations that lead to a lot of horror films being unavailable or heavily edited. Due to magazines such as Fangoria and Starburst, fans would be aware of both mainstream US and independent productions long before they were released in the UK. Hence we’d often become aware of those occasional titles that had already caused a stir “stateside” or in Europe and would therefore naturally run into distribution and censorship issues when it came to a British release. How could such films be shown in the UK? The answer was the “film festival”, which provided a limited or one off showcase, where the audience could be strictly regulated. Such events weren’t providing mainstream national distribution.

Now film festivals per se are always a great occasion for fans. I find that watching a cult classic with a like minded audience in a traditional movie theatre setting, rather than watching at home on your own, is a superior way to enjoy a film. I believe there is some truth to the “shared experience”. For example I feel the slapstick shenanigans of Charlie Chaplin work a lot better when viewed with a group. Bearing this in mind, on Saturday 24th February 1990, not only did I get the chance to indulge this theory by going to my first film festival but I was afforded the oppurtunity to see a controversial film that was heading into trouble. That film being Henry Portrait of a Serial Killer. The Splatterfest 90 film festival was held at the Scala Cinema, in Kings Cross, London. The venue was a known private cinema that excelled at hosting such events, as well as regularly showing bizarre and baroque movies.

I remember quite clearly, the atmosphere in the cinema. The Scala was a sumptuous but somewhat dilapidated 1920s building, which lent itself well to its niche market purpose. Between films it was quite noisy with fans talking and constantly going to and fro to the lobby. But when Henry Portrait of a Serial Killer started the audience settled and fell silent. The film was a gruelling 83 minutes experience which left the audience shocked, uncomfortable yet utterly engaged with the proceedings. I subsequently learned that several examiners from the BBFC had attended the screening as an opportunity to “research” a movie they knew would be “problematic” when it eventually sought a formal UK theatrical release. There was a very interesting Q&A with director John McNaughton which shed a lot of insight into the film and its production.

There were several other movies shown that night making Splatterfest 90 a very enjoyable film festival. Brian Yuzna’s Bride of Re-Animator which is a great sequel to the original Re-Animator, was very well received. As was the excellent documentary Document of the Dead, which was made during the filming of George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead. However, one film did not go down particularly well. The Comic, a “psychological drama” about a stand up comedian who murders his way to success in a dystopian future, was met with derision, objects hurled at the screen and cries of “for fuck’s sake, turn this shit off”. Director Richard Driscoll was due to be interviewed after the screening but bid a hasty retreat after his film’s suboptimal reception. Overall Splatterfest 90 was a very good introduction to film festivals and was certainly a “grassroots” experience of fandom. I’ve been to many similar events since then but none have had quite the same impact or left such memories as this one.

An Ode to the VCR

Sometimes it really helps to have “been there” to fully appreciate an event or cultural phenomenon. We now live in an age where there is easy access to a multitude of television channels and movies, 24 hours a day. TVs are no longer bulky, luxury items that sit in a corner of your lounge. They are now elegant flat screened devices that occupy nearly an entire wall, offering crystal clear, high definition picture quality. Movies are now available for home viewing a lot sooner after their theatrical release and the current pandemic has brought the era of simultaneous release on all platforms just a little bit closer. And even the most obscure and niche market films are accessible in a remastered, HD or UHD format. It’s all a far cry from my youth when cinema and television were far more compartmentalised and consumers had far less choice along with access. All of which you can explain to those born into this modern world of plenty but they’ll never fully comprehend the realities of living such a life and in such times.

The Sony C6 Betamax VCR. A “Titan” in the format wars