The Songs of Middle-earth: Part Two

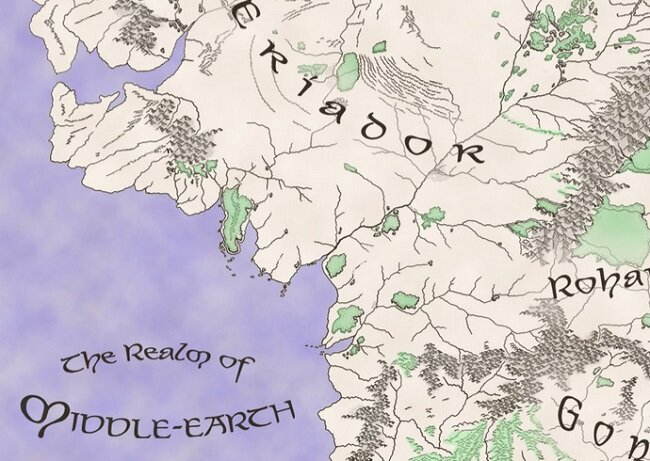

Song is a fundamental aspect of Tolkien's writing, serving the same role as it does in our own cultures. It is a means of documenting history, expressing cultural heritage and maintaining traditions for the people of Middle-earth. The Ents sing lists of lore. The Rohirrim sing of battle and heroic deeds and the Shire folk, of ale and frivolity. Let us not forget that Tolkien’s fictitious world, Arda, was effectively sung into existence via the Ainulindalë, the divine music of creation sung by the Ainur. The cultural significance of song is also a key element of Tolkien’s world building. The songs within the narrative bolster the authenticity of the various cultures of Middle-earth, embedding their history and heritage into the story. Music, rhymes and songs also help define characters. The lighter ones sung by hobbits, provide lighthearted moments, contrasting with the dark and dangerous tones of the larger narrative. It also reinforced their rustic heritage.

Song is a fundamental aspect of Tolkien's writing, serving the same role as it does in our own cultures. It is a means of documenting history, expressing cultural heritage and maintaining traditions for the people of Middle-earth. The Ents sing lists of lore. The Rohirrim sing of battle and heroic deeds and the Shire folk, of ale and frivolity. Let us not forget that Tolkien’s fictitious world, Arda, was effectively sung into existence via the Ainulindalë, the divine music of creation sung by the Ainur. The cultural significance of song is also a key element of Tolkien’s world building. The songs within the narrative bolster the authenticity of the various cultures of Middle-earth, embedding their history and heritage into the story. Music, rhymes and songs also help define characters. The lighter ones sung by hobbits, provide lighthearted moments, contrasting with the dark and dangerous tones of the larger narrative. It also reinforced their rustic heritage.

Eight years ago I collated three songs that were either inspired by Tolkien’s writings or were indeed specific songs from the source text that had been set to music. These can be found here; The Songs of Middle-earth: Part One. The post was originally intended to be part of a series, so I therefore thought it was high time that I wrote about another three, as there is still so much material to choose from. Once again I have chosen two which are clear adaptations of songs in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings and have been set to music. Then there is one which is an original piece, though clearly inspired by Tolkien’s Legendarium and sung in Quenya. I have also added the lyrics and where necessary an English translation.

Gil-galad was an Elven king is a poem consisting of three stanzas, spoken aloud by Sam Gamgee in The Fellowship of the Ring. It is a brief account of Gil-galad, the last High King of the Noldor and his death during the siege of Barad-dûr at the hands of Sauron. Sam states that he learned the verse from Bilbo Baggins but Strider then asserts that it is part of a larger, older piece, written in an ancient tongue (probably Quenya) and that Bilbo no doubt translated it into the common speech. The song version presented here is from the BBC radio adaptation of The Lord of the Rings. The music is by Stephen Oliver and composed in the English pastoral tradition, The vocalist is actor and singer Oz Clarke who adopts a baritone style.

Gil-galad was an Elven king

Of him the harpers sadly sing

The last whose realm was fair and free

Between the mountains and the sea

His sword was long, his lance was keen

His shining helm afar was seen

And all the stars of heaven's field

Were mirrored in his silver shield

But long ago he rode away

And where he dwelleth none can say

For into darkness fell his star

In Mordor where the shadows are

Misty Mountains features in Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. The music is written by Howard Shore and the words are an abbreviated version of the original song written by J.R.R. Tolkien in the book The Hobbit. Sung by the character Thorin Oakenshield, played by actor Richard Armitage, the rest of the cast provide additional vocals. The song itself is an oral history of how the kingdom of Erebor was attacked by the Dragon Smaug and how the dwarves were driven from their home. It is sung “a cappella” and has an almost “Gregorian chant” religious quality to it. The song was subsequently used as a leitmotif throughout the remainder of the film.

Far over the Misty Mountains cold

To dungeons deep and caverns old

We must away, ere break of day

To find our long forgotten gold

The pines were roaring on the height

The winds were moaning in the night

The fire was red, it flaming spread

The trees like torches blazed with light

Golden Leaves is an original song composed by Bear McCreary for the first episode of the second season of the Amazon Prime series The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power. It features lyrics sung in Quenya by actor Benjamin Walker, who plays Gil-galad, the last High King of the Noldor. The song is a lament for the fading of the Elves in Middle-earth and how it is time to return to Valinor. According to Bear McCreary, the lyrics were created by John D. Payne and were inspired in part by the lyrics Tolkien wrote for Galadriel’s Song in The Fellowship of the Ring. Dialect coach Leith McPherson guided Benjamin Walker’s pronunciation of the Quenya text. Characters expressing themselves in song is a core tenet of Tolkien’s writing and Golden Leaves reflects that admirably.

Sís laurië lassi taiter,

yénin linwavandië.

Anpalla Vai Ahtalëa,

sí lantar Eldaniër.

Eldalié! Eldalié!

Hrívë túla helda ré úlassëa.

Eldalié! Eldalié!

I lassi lantar celumenna.

(Children’s choir:) Cormar nelde aranin Eldaron

Eldalié and’ amárielvë

ambena solor.

Sí néca riëmancan,

viliën an Valinor

Eldalié! Eldalié!

Hrívë túla helda ré úlassëa.

Eldalié! Eldalié!

I lassi lantar celumenna.

Here long the golden leaves grew,

on years branching.

For beyond the Sundering Seas,

now fall Elven-tears.

O’ Elven-kind! O’ Elven-kind!

Winter is coming, bare leafless day.

O’ Elven-kind! O’ Elven-kind!

The leaves are falling in the stream.

(Children's choir:) Three rings for the Elven kings

Elven-kind long have we dwelt

upon this hither shore.

Now fading crown I trade,

to sail to Valinor.

O’ Elven-kind! O’ Elven-kind!

Winter is coming, bare leafless day.

O’ Elven-kind! O’ Elven-kind!

The leaves are falling in the stream.

Conservatives and Tolkien

I don’t know if you have noticed that there are quite a lot of companies that have names taken from Tolkien’s Legendarium. At first glance, this seems innocuous enough. Tolkien’s writings grew in popularity over the seventies and eighties but since the release of the film trilogy at the start of the twenty-first century, his work has become more well known and been assimilated into our wider pop culture. Hence, it seems quite logical that a startup tech company, for example, would choose a name from his writings. No doubt the founders grew up reading The Lord of the Rings and are fans. That all seems plausible. However if you take a further look, it gets somewhat more complex. Here are four companies that have Tolkien based names.

I don’t know if you have noticed that there are quite a lot of companies that have names taken from Tolkien’s Legendarium. At first glance, this seems innocuous enough. Tolkien’s writings grew in popularity over the seventies and eighties but since the release of the film trilogy at the start of the twenty-first century, his work has become more well known and been assimilated into our wider pop culture. Hence, it seems quite logical that a startup tech company, for example, would choose a name from his writings. No doubt the founders grew up reading The Lord of the Rings and are fans. That all seems plausible. However if you take a further look, it gets somewhat more complex. Here are four companies that have Tolkien based names.

Palantir Technologies is a private American software and services company, specializing in data analysis. Named after the “seeing stones” from Tolkien's legendarium, Palantir's original clients were federal agencies of the United States Intelligence Community like CIA and NSA.

Lembas Capital is a San Francisco-based investment firm named after the Elven waybread that appears in The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion. The company invests in both public equity and private equity.

Valar Ventures, named after the Valar, is a US-based venture capital fund founded by Andrew McCormack.

Anduril Industries, named after Aragorn' sword, is an American defence technology company that specializes in autonomous systems.

I don’t consider banks, armaments suppliers and intelligence gatherers to be benign. Yes there are other companies with Tolkieneque names that are doing benevolent things but there are enough doing the opposite for me to consider that there’s something else going on. In this case, the common thread is that political conservatism embraces and feels an affinity to the writings of Professor Tolkien. In fact conservatives from both the US and Europe often cite The Lord of the Rings as a source of inspiration.

Why is this you may ask? Mainly because right-wing politicians are drawn to Tolkien's themes of the heroic struggle against corrupt systems, the return of a legitimate ruler to restore social order and a conservatively hierarchical worldview that reflects medieval Catholic ideas. There is also a suspicion of social modernity. The appeal lies in the narrative of a righteous hero or group challenging a “moribund establishment” to build a “brave new world that reflects a former past glory”. Such ideas resonate with right-wing figures who see themselves as fighting for traditional values against societal collapse. Politicians such as US Vice President J.D. Vance, former Member of theEuropean Parliament Lord Hannan and the Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

Here are some of the key themes and interpretations that appeal to conservatives.

Heroic Mission and World-Making: Politicians see a parallel between their own political aspirations and Tolkien's heroes, who feel a "duty to save the world" and build a better future.

"Return of the King" and Feudal Order: The core narrative of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings involves the re-establishment of a rightful monarch and the restoration of a pre-existing feudal social structure after a period of chaos. This narrative strongly appeals to conservative viewpoints.

Conservative Values and Hierarchy: Tolkien's work is seen by some as aligning with conservative principles due to its depiction of a divinely ordained natural hierarchy, echoing medieval Catholic notions of the "Great Chain of Being" and a worldview that favors traditional social orders over modernity.

Critique of Modernity: Influenced by his experiences and his devout, pre-Vatican II Catholic faith, Tolkien harbored a deep suspicion of modernity, a sentiment that resonates with many on the right who view modern trends as destructive.

Anti-Totalitarianism: While some interpretations of Tolkien focus on conservative themes, others emphasise his opposition to totalitarian systems. This could also appeal to those who view themselves as fighting against oppressive governments or ideologies.

Like many things political, there is an inherent contradiction to much of the above. The drive to build a better world usually means a better world for that specific political class. The restoration of a prior status quo seldom means it is an equitable one. Critiques of modernity are usually against changes in social attitudes, though not technology as that is a useful tool. As for opposing totalitarianism, this usually means circumnavigating legitimate opposing views or institutions that don’t allow conservatives a free hand. But such is the nature of politics and its use of semantics. As for the question of whether these specific interpretations of Tolkien’s work are actually there in the source text, that is highly subjective.

It helps us understand things much better if we can actually determine what were Tolkien’s own personal politics? Well he most certainly was a conservative both politically and socially but within the context of the times he grew up in. Hence despite the sharing of the term, I don’t really think there is a great similarity between Tolkien’s form of Catholic conservatism and his post WWI social sensibilities and a modern American neocon. Tolkien by his own admission disliked political organisations and institutions, claiming an affinity to non-violent anarchism. He was also anti-fascist and sceptical of industrial capitalism, albeit from a romantic perspective. He was also an ardent environmentalist.

Perhaps Tolkien’s biggest appeal to conservatives is his passion for mythology. Myths are a lens through which we explore the mysteries of the world around us and then use to codify and quantify it. Change the myth and you can change the world, as JRR Tolkien well knew. Which is why he spent his life creating new myths to help us better understand the modern world. An understanding tempered by his own world views. It is this that attracts many politicians on the right, who see mythology as means to frame their populist ideas. Political narrative and mythology have many similarities and are rife with archetypes and heroes.

I’m sure we’re now at the point where some readers may argue “so what if the right finds inspiration in Tolkien’s work” as well as “many fans will interpret things in that which they hold dear, irrespective of whether it is truly there or not”. All of which is true. We all see things through the prism or our own passions, or bias if you prefer. However we live in a world where nuance is in decline. The claiming of aspects of pop culture by specific groups can sometimes have negative consequences, mainly for that which is being claimed. Already because conservatives have stated an affinity for Tolkien’s work, some on the left are already seeking to find content connecting it to the right. Hence there have been claims, unsubstantiated in my view, that The Lord of the Rings is inherently racist and therefore by extension, so was the author and those who read it. There is a risk that the failings of the right may inadvertently blight the cultural standing of Tolkien work, simply by an act of non consensual association.

Which is why I feel the need to push back against the risk of such a thing. I do not believe that Tolkien’s work should just be surrendered to the politically and socially conservative. I’d also prefer not to see certain types of companies usurping Tolkien’s work for their own agendas and chronically misinterpreting his work. Or worse still, doing so just to be associated with something that is “cool”. Perhaps Robert T. Tally Jr. professor of English at Texas State University, said it best “In 2024, a number of prominent right-wingers embrace Tolkien’s work as the inspiration for their own ultraconservative worldview. While some Marxists may look upon this scene with bemusement, fantasy as a mode and a genre is far too important to allow the right-wingers to take for themselves, and that includes the works of Tolkien”.

The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power Trailer

Finally the first teaser trailer for Amazon Prime’s forthcoming TV show set in the Second Age of Middle-earth has been released. The Lord Of The Rings: The Rings of Power will be released weekly on Amazon’s streaming service commencing September 2nd 2022. The first season consists of eight episodes. The series is a prequel to the events of The Lord of the Rings, depicting "previously unexplored stories" based on Tolkien's works. The show will include such iconic locations as the Misty Mountains, the elf-capital Lindon, and the island kingdom of Númenor. The Lord Of The Rings: The Rings of Power maintains the visual and design aesthetic of the existing Peter Jackson movies. Furthermore, composer Howard Shaw maintains his involvement as does artists and designer John Howe. Apparently, due to the Tolkien Estate being happy with the development of the show, Amazon had gained access to certain elements and passages from The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales to include in the narrative arc.

Finally the first teaser trailer for Amazon Prime’s forthcoming TV show set in the Second Age of Middle-earth has been released. The Lord Of The Rings: The Rings of Power will be released weekly on Amazon’s streaming service commencing September 2nd 2022. The first season consists of eight episodes. The series is a prequel to the events of The Lord of the Rings, depicting "previously unexplored stories" based on Tolkien's works. The show will include such iconic locations as the Misty Mountains, the elf-capital Lindon, and the island kingdom of Númenor. The Lord Of The Rings: The Rings of Power maintains the visual and design aesthetic of the existing Peter Jackson movies. Furthermore, composer Howard Shaw maintains his involvement as does artists and designer John Howe. Apparently, due to the Tolkien Estate being happy with the development of the show, Amazon had gained access to certain elements and passages from The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales to include in the narrative arc.

The trailer itself reveals no footage from The Lord Of The Rings: The Rings of Power. Its primary purpose is to formally announce the new TV show’s name and to set out its stall. However, it is worth noting that like the TV show itself, Amazon went all in with the actual trailer. The first season is alleged to have had a production cost of $465 million. Although no data appears to be available on the budget for the trailer, it features the talents of director Klaus Obermeyer, legendary special effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull renowned foundryman Landon Ryan. I’m sure such an ensemble production team does not come cheap. As for the teaser trailer itself, it is suitably evocative of ring forging and the threat of dark powers. The lush soundtrack is certainly in the established idiom of “the sound of Middle-earth”. It has piqued both mine and a good many other people's curiosity.

I recently discovered both of the original theatrical trailers for the 1978 animated version of The Lord of the Rings created by Ralph Bakshi. One is simply a portentous narration but the second is far more interesting. It features a montage of still images. Some of them are background paintings used in the movie, while others seem to be production art. The voice-over descends into hyperbole and is somewhat misleading, but you have to remember that the fantasy genre was not a common staple of the box office of the times. Like many films the pre-production process can often produce an inordinate amount of material that never makes it into the final edit. Some of this can be seen in the trailer. It’s interesting to see how Tolkien’s work has grown in popularity within popular culture over the last forty years and how that is reflected in the difference between the two trailers.