Friday the 13th Part III (1982)

Set directly after the events of the previous film, Friday the 13th Part III is again about a group of friends staying near Crystal Lake who encounter Jason Voorhees as he embarks upon another killing spree. Shot in 3D the film has a less sleazy tone than its predecessors although the formula remains the same. The set pieces and death scenes are more elaborate and less clinical, taking advantage of the 3D picture format. The film marks the first appearance of Jason's signature hockey mask, which subsequently became a trademark of both the character and the franchise. Originally conceived to be an end to the series of films, Friday the 13th Part III performed extremely well at the box office, earning $36.7 million on a budget of $2.2 million. As a result, the franchise was given a stay of execution and a further sequel was commissioned.

Set directly after the events of the previous film, Friday the 13th Part III is again about a group of friends staying near Crystal Lake who encounter Jason Voorhees as he embarks upon another killing spree. Shot in 3D the film has a less sleazy tone than its predecessors although the formula remains the same. The set pieces and death scenes are more elaborate and less clinical, taking advantage of the 3D picture format. The film marks the first appearance of Jason's signature hockey mask, which subsequently became a trademark of both the character and the franchise. Originally conceived to be an end to the series of films, Friday the 13th Part III performed extremely well at the box office, earning $36.7 million on a budget of $2.2 million. As a result, the franchise was given a stay of execution and a further sequel was commissioned.

First drafts of the screenplay for Friday the 13th Part III, focused upon the previous “final girl” Ginny Field (Amy Steel), who was trying to re-adjust to normal life after her traumatic experience at Crystal lake. However, Amy Steel declined the part and so writers Martin Kitrosser and Carol Watson opted to follow the established formula. Hence the story is about eight friends staying for a weekend at a holiday cabin near Crystal Lake. The property belongs to Chris Higgins (Dana Kimmel). Chris reveals to her boyfriend Rick (Paul Katka) that she was attacked by a deformed man two years earlier and has come home to face her fears. The other guests are Debbie (Tracie Savage), her boyfriend Andy (Jeffrey Rogers), prankster Shelly (Larry Zerner), his blind date Vera (Catherine Parks) and stoners Chuck (David Katims) and Chili (Rachel Howard).

As Friday the 13th Part III was filmed in 3D it had a higher budget than the two previous films. Director Steve Miner manages the pace well, providing two deaths early on to wet the audience’s appetite, then spending the next twenty five minutes on introducing the characters and building tension. The “teenagers” are not as grating as usual and there is minor comic relief from both Shelly and Chuck. The death scenes make good use of the 3D photography, with all manner of objects being hurled at the camera. The two kills that get the biggest audience reaction are Jason crushing a head with his bare hands, resulting in an eye popping out. Another character is bisected with a machete from his crotch to his navel, while walking on his hands. Harry Manfedini once again provides an appropriate score, with an especially funky theme during the opening credits.

Friday the 13th Part III is one of two instalments in the franchise that manages to rise above its exploitation roots. The other is the sixth, Jason Lives. The third instalment gained a veneer of quasi-respectability by being in 3D. It made the movie an “event” at the time of its release, as the revival of this format had not yet outstayed its welcome. From a continuity perspective the third film is all over the place. The events depicted are 24 hours after those of Part 2, technically making the film Saturday the 14th. Jason seems to have gained height and shaken off having a machete cleave his left shoulder. But none of it really matters. The film once again delivers what viewers want and this time in glorious 3D. It can even be argued that there is a degree of charm to it all or at least some sense of novelty. The film certainly suits the medium of 3D and it can be argued that it is the best in the series.

Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981)

Originally, Friday the 13th Part 2 was intended to be an anthology film based on the superstition associated with the date. However, after the popularity of the original film's surprise ending, the producers opted to continue the story and mythology surrounding Camp Crystal Lake. This eventually became the parameters which all future films would broadly work within. Friday the 13th Part 2 is a more polished production than the first movie, benefitting from twice the budget of the original. The quick turnaround meant that Paramount Pictures could continue to capitalise on the popularity of the slasher genre. However, there was growing social pushback against these types of films, from Christian lobby groups and other “concerned parties”. Hence, Friday the 13th Part 2 ran into problems with the MPAA ratings board and cuts were imposed. Something that would continuously plague the franchise over the years.

Originally, Friday the 13th Part 2 was intended to be an anthology film based on the superstition associated with the date. However, after the popularity of the original film's surprise ending, the producers opted to continue the story and mythology surrounding Camp Crystal Lake. This eventually became the parameters which all future films would broadly work within. Friday the 13th Part 2 is a more polished production than the first movie, benefitting from twice the budget of the original. The quick turnaround meant that Paramount Pictures could continue to capitalise on the popularity of the slasher genre. However, there was growing social pushback against these types of films, from Christian lobby groups and other “concerned parties”. Hence, Friday the 13th Part 2 ran into problems with the MPAA ratings board and cuts were imposed. Something that would continuously plague the franchise over the years.

Second time round the film boasts a nominally stronger script by Ron Kurz with better defined characters. Amy Steel stars as camp counsellor Ginny Field and continues the tradition of a robust and dynamic “final girl”. Betsy Palmer makes a cameo appearance as the late Pamela Voorhees and prophet of doom, Crazy Ralph (Walt Gorney), returns briefly before an unpleasant demise. The boldest step in the screenplay is a major retcon of Jason Voorhees, who has now survived the drowning incident of his youth, having lived as a hermit in the woods for twenty five years. Like so many genre films, it’s best not to dwell too much on the plot details as they’re seldom logical. The larger budget meant better production values. The cinematography by Peter Stein is more atmospheric this time round. But the main focus of attention are the set pieces and death scenes.

Tom Savini passed on the opportunity to return and undertake the film’s makeup effects. Stan Winston was briefly involved in the production but then left due to scheduling conflicts. Finally Carl Fullerton, apprentice to the legendary Dick Smith, took on the project. He has crafted some excellent death scenes, two of which bear an uncanny similarity to those seen in Mario Bava’s A Bay of Blood. However, rather than this being a homage it would appear that they occurred purely by luck. Sadly most of these effects sequences were shortened by the MPAA to the point where it’s difficult to discern what is happening on screen. Thankfully the excellent new HD transfers by Shout Factory help with these details. I noticed for the first time that the throat cutting and the machete to the face scenes both use the wrong side of the weapon for safety reasons.

The final 25 minutes of Friday the 13th Part 2 are well conceived and executed. The chase between Jason and Ginny is well paced and tense. At one point Ginny hides from Jason under a bed and a rat scurries past her. It is discreetly implied that Ginny wets herself out of sheer fear, which is a curious but credible minor detail. The denouement in a dilapidated shack where Jason has a shrine to his dead mother Pamela Voorhees is suitably creepy. Due to the clarity of the Blu-ray transfer, details such as Alice’s body, the “final girl” from the previous movie, are far more apparent. Harry Manfredini’s score continues to be very effective, especially in the chase sequence. Overall this is a solid sequel, offering more of the same but with a little more attention to detail. Friday the 13th Part 2 lays the foundations for future instalments of the franchise. The only thing missing is Jason’s iconic hockey mask which doesn’t appear until the next film.

Friday the 13th (1980)

Writing any kind of review for the original Friday the 13th movie seems somewhat redundant, as it has been analysed and written about numerous times before. If you’re interested in the film’s production as well as its subsequent impact on US cinema at the time, then there is an excellent summary on Wikipedia. Having recently rewatched the entire franchise, courtesy of the Shout Factory’s Friday the 13th Collection Deluxe Edition, I have a few thoughts I’d like to share. The picture quality of all the films is very good, offering a lot more visual information compared to previous releases. The amount of “extras” included in the box set is prodigious. I suspect that these are the best versions that we’re ever likely to see. Fans hoping that one day all the cut footage will be found and re-integrated into each film are likely to remain disappointed. Some material has surfaced but sadly a lot of deleted and extended scenes have been destroyed.

Writing any kind of review for the original Friday the 13th movie seems somewhat redundant, as it has been analysed and written about numerous times before. If you’re interested in the film’s production as well as its subsequent impact on US cinema at the time, then there is an excellent summary on Wikipedia. Having recently rewatched the entire franchise, courtesy of the Shout Factory’s Friday The 13th Collection Deluxe Edition, I have a few thoughts I’d like to share. The picture quality of all the films is very good, offering a lot more visual information compared to previous releases. The amount of “extras” included in the box set is prodigious. I suspect that these are the best versions that we’re ever likely to see. Fans hoping that one day all the cut footage will be found and re-integrated into each film are likely to remain disappointed. Some material has surfaced but sadly a lot of deleted and extended scenes have been destroyed.

Made to capitalise on the success of John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), Friday the 13th is a far more contrived and cynical piece of filmmaking. Director Sean S. Cunningham aimed to provide audiences with a cinematic “rollercoaster ride”. A horror experience which included all the things the target audience wanted. Specifically sex and violence. The screenplay by Victor Miller offers nothing more than the functional. The scene is set, the characters introduced and then the killing begins. There are a few red herrings along the way but there is little in the way of character development or thematic exploration. Instead we get a litany of stereotypes, although they are used effectively. The cinematography by Barry Abrams is simple, bordering on stark. The production was shot on a real Boy Scout Camp and it is suitably dilapidated giving the proceedings an authentic feel.

The film’s main innovation was the quality of the makeup effects and set pieces. These are jarringly clinical at times, courtesy of Tom Savini. The final revelation that the killer is in fact the mother of a boy who died at the summer camp is also a highpoint. Betsy Palmer’s performance is suitably unhinged. Several other members of the cast are of interest. Kevin Bacon appears as one of the camp counsellors and has possibly the best death scene. Bing Crosby’s son, Harry Crosby, also makes an appearance. Within a few years, he quit acting altogether and became an investment banker. Underpinning all of this is an atmospheric score by Harry Manfredini. Manfredini’s major innovation is a vocal motif, “ki ki ki ma ma ma”, which is played whenever the killer’s POV was used. Along with its use of strident strings during chase sequences, the score for Friday the 13th has become iconic.

Although made independently, Friday the 13th was distributed by Paramount Pictures. The studio was interested in the “youth market” during the late seventies and saw the film as a low risk investment. Paramount were not pleased by the negative reviews the film garnered and some senior executives did not like the studio being associated with such exploitation material. However, Friday the 13th grossed over $59 million at the box office worldwide. A significant achievement for a film that was made for half a million. Not only did it prove a sound investment for Paramount, it effectively started an entire sub-genre within horror movies. Film critics can sometimes find themselves at odds with audiences and Friday the 13th is a prime example of this. They failed to see that the film was a straightforward quid pro quo. Despite its rough edges, it gave audiences exactly what they wanted and they were happy to pay. It didn’t need to be any more than the sum of its parts.

Theatrical Version or Director's Cut?

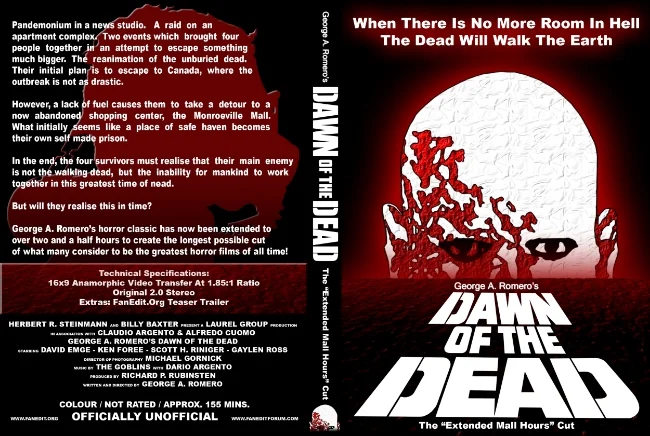

Not all film director’s have the luxury of “final cut”. The right to ensure that the completed version of a film corresponds with their creative vision. Films are commercial undertakings and sometimes the producers, film studio or other interested parties get to assert their wishes over that of the director. Often this can be due to practical considerations such as running time or budget. On occasions, this can be down to major creative and artistic differences. Hence the theatrical release of a film may be considered flawed, unfinished or just plain wrong by the director, if changes have been imposed, regardless of the reasons. Therefore, a director’s cut of a film can offer a significantly different cinematic vision over the original theatrical release. They can present an opportunity to fix perceived problems or just put more narrative meat on the bones. This may lead to a film being critically reappraised.

Not all film director’s have the luxury of “final cut”. The right to ensure that the completed version of a film corresponds with their creative vision. Films are commercial undertakings and sometimes the producers, film studio or other interested parties get to assert their wishes over that of the director. Often this can be due to practical considerations such as running time or budget. On occasions, this can be down to major creative and artistic differences. Hence the theatrical release of a film may be considered flawed, unfinished or just plain wrong by the director, if changes have been imposed, regardless of the reasons. Therefore, a director’s cut of a film can offer a significantly different cinematic vision over the original theatrical release. They can present an opportunity to fix perceived problems or just put more narrative meat on the bones. This may lead to a film being critically reappraised.

However, it is erroneous to assume that a director’s cut is a superior version of a film by default. Sometimes, a filmmakers desire to return to a previous project and make alterations yields no significant results. Some director’s even develop a reputation as “serial tinkerers” who never seem to be satisfied, whatever the results. Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now exists formerly in three distinct versions. Oliver Stone has released four versions of his film Alexander (2004). As for George Lucas, he stated in an interview that “films are never completed, they’re only abandoned”. He has famously revisited his body of work several times and not necessarily to their overall benefit. With all this in mind, here are three films, where popular opinion and critical acclaim favours the original theatrical version over the later released director’s cut.

Alien (1979). Ridley Scott is another well known director who always seems to revisit his work and make alterations. His reasons for re-editing vary and sometimes they do yield better movies. However, the original theatrical release of Alien is described by Scott himself as “the best he could possibly have made at the time”. Yet in 2003, he released a “director’s cut” despite stating that this was not his definitive version. The new version restored roughly four minutes of deleted footage, while cutting about five minutes of other material, leaving it approximately a minute shorter than the theatrical cut. The standout changes were to Brett’s death scene which shows more of the xenomorph and the infamous scene where Ripley finds Dallas “cocooned” and puts him out of his misery. Being no more than a fan service, this version has no additional value. In fact it can be argued that it only serves to contradict the xenomorph’s established biology.

Donnie Darko (2001). Richard Kelly had to compromise when making his off kilter science fiction movie. The main one being keeping the running time below two hours. In 2004, director Kelly, re-cut the film, added twenty minutes of previously deleted footage as well as new music and sound effects. This director's cut provides a clearer insight into many of the film's more ambiguous plot elements and makes the previously vague temporal mechanics less esoteric. However, critics and fans alike have stated that the charm of the theatrical release lies in its mysterious and ill defined nature. It is a deliberately enigmatic cinematic journey. Kelly’s second edit may well add clarity but in doing so neuters what so many viewers found endearing. Sometimes, less is indeed more.

The Warriors (1979). Walter Hill’s underrated, stylised gang drama has its roots in the writings of ancient Greek professional soldier Xenophon. The theme of a group of warriors trapped in hostile territory and trying to get home is cleverly transposed to seventies New York City. Made on a tight schedule by a studio that wasn’t especially enamoured with the material, Hill didn’t get to draw the exact parallels he originally wanted. Hence in 2005, he added a new opening scene with a voiceover describing how Xenophon’s army attempted to fight its way out of Persia and return home. He also inserted comic-book splash panel shots as a means to bridge various key scenes in the film. Sadly, this was a little too on the nose and too expository. Recent releases of The Warriors on Blu-ray and UHD have included both versions and the consensus remains that the theatrical release is more efficient, requiring no further embellishment.

Day of the Dead (2008)

George A. Romero's Day Of The Dead (1985) is a bleak and remorseless masterpiece. The final entry in his “Dead Trilogy”, its central theme is that in a world on the brink of destruction, man is still the biggest threat to his own existence. It is well scripted, clinically accurate in its observations on human nature and thought provoking, despite having its budget cut just weeks before production commenced. 40 years later it is revered as a genre milestone and is considered one of Romero’s finest works. Sadly, the 2008 “remake” directed by Steve Miner, who has a background in slasher and exploitation movies, takes a contrasting approach, to say the least. It certainly has very little to do with Romero’s film and one can’t help but assume that it is nothing more than a cynical cash in. Setting aside comparisons with the original, this is not in any way a standout zombie film in its own right.

George A. Romero's Day Of The Dead (1985) is a bleak and remorseless masterpiece. The final entry in his “Dead Trilogy”, its central theme is that in a world on the brink of destruction, man is still the biggest threat to his own existence. It is well scripted, clinically accurate in its observations on human nature and thought provoking, despite having its budget cut just weeks before production commenced. 40 years later it is revered as a genre milestone and is considered one of Romero’s finest works. Sadly, the 2008 “remake” directed by Steve Miner, who has a background in slasher and exploitation movies, takes a contrasting approach, to say the least. It certainly has very little to do with Romero’s film and one can’t help but assume that it is nothing more than a cynical cash in. Setting aside comparisons with the original, this is not in any way a standout zombie film in its own right.

A group of soldiers led by Captain Rhodes (Ving Rhames) seal off a remote town in Colorado, due to an alleged viral outbreak. Corporal Sarah Cross-Bowman (Mena Suvari) soon suspects that matters are much worse when the infected’s symptoms change from coughing and nosebleeds, to necrosis and a penchant for cannibalism. Has Doctor Logan (Matt Rippy) from the CDC, been sent to help or is he part of a covert project that has gone awry? Cue mayhem, death, bad acting and teenagers in peril. Absolutely no cliche is left unturned from “let's split up” to the ubiquitous wisecracking, African American comic relief. There are ludicrous levels of pseudoscience even by this genre’s standards and the curious addition of zombies climbing around walls and ceilings like Spider-Man, which just doesn’t work.

Filmed mainly in Sofia, Bulgaria Day Of The Dead has a somewhat low budget feel. Cinematographer Patrick Cady does his best to create an atmosphere and cover the modest nature of the production. Yet rather than innovate, the film takes an “everything bar the kitchen sink” approach. Every possible trope from the genre is included and then poorly executed. The make up effects and prosthetics are adequate but the film lacks any standout set pieces. The digital fiery denouement is over far too quickly due to budgetary restrictions, making the ending lacklustre. Perhaps the biggest mistake that Day Of The Dead makes is when Private Bud Crain (Stark Sands) is bitten and becomes a zombie. He eschews his undead nature because he was a vegetarian when alive. Perhaps writer Jeffrey Reddick thought he was making a clever point but regardless of the intent it simply comes off as risible.

Steve Miner has been involved with some interesting films over the years. I enjoyed his homage to creature features, Lake Placid and the gothic Warlock. Two Friday 13th sequels loom large in his body of work. But this is far from his finest hour. Zack Snyder's 2004 remake of Dawn Of The Dead may not be to everyone’s tastes but it cannot be accused of being a shallow, teen oriented exploitation piece. This film most definitely can be. It would appear that the distributors got wind of its shortcomings and so it bypassed cinemas and was released direct to video. If you’re looking for a clever reimagining of a seminal film, offering new perspectives on the zombie genre, then you won’t find it here. If you wish to waste 90 minutes of your time watching an uninspired, generic horror vehicle that seeks to capitalise on the kudos associated with the original, then this remake will meet those requirements.

Caligula: The Ultimate Cut (1979)

There are many stories and anecdotes associated with the 1979 film Caligula. Many of which are apocryphal. However, there is absolutely no doubt that this was a troubled production, with artistic differences between the writer, director and producers. Hence the original theatrical release was not the arthouse, historical drama that it was intended to be. Instead Caligula ended up the most notorious multimillion dollar independent film of the seventies. Steeped in violence, hardcore pornography and acts of depravity, yet boasting an A list cast of British and European actors, a screenplay by the legendary Gore Vidal and an established Italian arthouse director, namely Giovanni “Tinto” Brass . This magnificent cinematic car crash of a film has maintained an interest with cult film enthusiasts, as well as scholars of cinema over the decades. This is mainly because there’s an optimistic school of thought that there is a far better film trying to get out.

There are many stories and anecdotes associated with the 1979 film Caligula. Many of which are apocryphal. However, there is absolutely no doubt that this was a troubled production, with artistic differences between the writer, director and producers. Hence the original theatrical release was not the arthouse, historical drama that it was intended to be. Instead Caligula ended up the most notorious multimillion dollar independent film of the seventies. Steeped in violence, hardcore pornography and acts of depravity, yet boasting an A list cast of British and European actors, a screenplay by the legendary Gore Vidal and an established Italian arthouse director, namely Giovanni “Tinto” Brass . This magnificent cinematic car crash of a film has maintained an interest with cult film enthusiasts, as well as scholars of cinema over the decades. This is mainly because there’s an optimistic school of thought that there is a far better film trying to get out.

For those unfamiliar with the film and its associated legend, Caligula was initially conceived as an historical drama about the rise and fall of the controversial Roman emperor. The film stars Malcolm McDowell in the title role, alongside Teresa Ann Savoy, Helen Mirren, Peter O'Toole, John Steiner, and John Gielgud. It was filmed in Rome at Dear Studios during 1976 and was intended to be a serious dramatic exploration of the theme that absolute power corrupts. Writer Gore Vidal wrote an original screenplay based upon historical sources to that effect. However, director Tinto Brass had other ideas and preferred the concept of Caligula being a born monster just waiting for an opportunity. Hence he rewrote the script with an emphasis on the sensational, although he kept much of the original dialogue. However, upon completion of principal photography, producer Bob Guccione (the publisher of Penthouse) took over editing of the film and shot additional pornographic scenes for inclusion in the theatrical cut. Controversy, outrage and lawsuits followed. Caligula then passed into cinematic legend.

Then in 2019, Thomas Negovan was hired to reconstruct a version of the film closer to the initial vision. Using the original camera negatives of 100 hours of footage unearthed in the Penthouse archive, along with an early draft of Gore Vidal’s script, Negovan has assembled a radically different cut of the film using alternate takes and abandoned footage. However, this has still proven a difficult undertaking as there is far from a consensus on what the original intentions of the production were. Was Caligula intended to be a pure historical drama or a stylised exploration of the themes of Roman decadence, filmed via the medium of Italian arthouse cinema? It would appear that Negovan has arrived somewhere between the two positions. There is now a clear thematic thread running through Caligula: The Ultimate Cut with the emperor portrayed as an anarchic free spirit who is consumed by his own desire to push the boundaries of his power. He is enabled by a coterie of sycophants and lackays, as well as political opportunists.

Film aficionados will spot the changes that Thomas Negovan has made immediately. The film opens with an impressive new animated title sequence featuring a young Caligula performing his eponymous dance. This has been created for the film by “Sandman” artist Dave McKean. Numerous key scenes are now shown in chronological order and many of the more infamous and salacious sequences make use of alternative takes. The new edit certainly presents a more nuanced performance by Malcolm McDowell and the actor himself is certainly pleased with the new edit. Helen Mirren has more screen time as Caligula’s wife, Caesonia, although the character is still somewhat underwritten. Overall there is a far more coherent narrative arc and the film no longer feels like a vehicle exclusively created for the depiction of debauchery and violence.

That being said, Caligula: The Ultimate Cut has not been thoroughly sanitised because it is impossible to do so. Hedonism and physical indulgence are baked into the film’s celluloid DNA. There is still a lot of male and female nudity, a double rape and a great deal of violence and tonal unpleasantness. In replacing certain shots with alternate material, the exploitative aspect of some scenes has been replaced with a somewhat colder and more clinical tone, which in some respects makes them more shocking. Especially the notorious fisting scene and the assassination at the end of the film, which involves an infanticide. Cinephiles will also lament the replacement of Bruno Nicolai’s original score along with the classical cues by Prokofiev and Khachaturian, with a new soundtrack by Troy Sterling Nies. It is nothing more than functional, where the original matched the baroque tone of the film.

Overall Caligula: The Ultimate Cut is probably the best cut of the film we’re ever likely to see. Has Thomas Negovan’s extensive reconstruction revealed a lost masterpiece amid the decadence and depravity of the previous theatrical edition? Not quite. The film remains a cinematic chimaera that veers between high drama and exploitative excess. It just does so in a far more coherent and efficient fashion this time round. It does highlight the baroque production design by Danilo Donati and showcase a far more rounded performance by Malcolm McDowell but this is never going to be a film that finds mass, mainstream appeal. This legendary production will remain a source of fascination for scholars of cinema but is ultimately too “out there” to become an accepted part of the established pantheon of arthouse masterpieces. It is a unique product of its time and now in this new version, a cinematic curate’s egg rather than a hot mess.

Longlegs (2024)

Although I was unaware of it, there was a guerrilla marketing campaign for Longlegs which was focused on the internet rather than traditional television adverts. Hence the film gained a lot of interest prior to its release and as well as some some disproportionate expectations. Then immediately after its theatrical debut, the matter was further compounded by a possible excess of gushing praise as the film was “over reviewed”. Therefore I maintained a degree of scepticism about Longlegs and tempered my expectations prior to watching it. Any film that is hailed as the next Silence of the Lambs, featuring a “traumatising” performance by Nicholas Cage needs to be keenly scrutinised so that its cinematic merits can be carefully separated from the surrounding hyperbole. After viewing I found Longlegs to be a finely honed, atmospheric and precisely targeted horror thriller but not the genre milestone that some would claim.

Although I was unaware of it, there was a guerrilla marketing campaign for Longlegs which was focused on the internet rather than traditional television adverts. Hence the film gained a lot of interest prior to its release and as well as some some disproportionate expectations. Then immediately after its theatrical debut, the matter was further compounded by a possible excess of gushing praise as the film was “over reviewed”. Therefore I maintained a degree of scepticism about Longlegs and tempered my expectations prior to watching it. Any film that is hailed as the next Silence of the Lambs, featuring a “traumatising” performance by Nicholas Cage needs to be keenly scrutinised so that its cinematic merits can be carefully separated from the surrounding hyperbole. After viewing I found Longlegs to be a finely honed, atmospheric and precisely targeted horror thriller but not the genre milestone that some would claim.

During the 1990s, FBI agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) is assigned by her supervisor William Carter (Blair Underwood) to an investigation of a series of murder-suicides in Oregon. In each case a father kills his family and then himself, leaving behind a letter with Satanic coding signed “Longlegs”. The handwriting belongs to a third party and not a family member. Hence Carter suspects that the crimes may have been instigated. Lee, who possibly has latent psychic powers, determines that each family had a 9-year-old daughter born on the 14th of the month. Furthermore, the murders all occurred within six days before or after the birthday itself and the murders form an occult triangle symbol on a calendar. Curiously, one date is missing. While talking to her mother Ruth (Alicia Witt), Lee receives a coded birthday card from Longlegs, warning her that revealing the source of the code will lead to her mother's murder.

Director Osgood Perkins creates a vivid visual and aural landscape which immediately draws the audience into the brooding sense of disquiet. The ambient soundtrack by Zilgi is sparse and often music is replaced by ominous tonal sounds. Perkins also furnishes just enough information both visually and within his screenplay, to keep viewers engaged but forcing them to fill in the narrative gaps themselves. At one point a character is shown to have a substantial supply of medication. Exactly what it is for is never specifically explained. Is it to treat a psychiatric condition of a specific illness? A character refers to the remote location where they and their daughter live and how no one visits them. Is this due to her being an unwedded mother or having some form of mental illness? Both would potentially make them a social pariah in small town America, during the sixties.

Nicholas Cage’s notable performance is not overplayed and his character only makes a few appearances during the film’s first act. His face is obscured initially and it is only during an FBI interrogation scene that we become aware of his curious demeanour. Again whether he is an albino or has acquired such a complexion by avoiding sunlight is never made clear. It is while he is questioned by agent Harker that Cage ups the ante and we become aware that he is not just another broken human being who has morphed into a serial killer. It is at this point that the film commits to a more overtly supernatural plotline, where initially it was deliberately more ambiguous. Beforehand, the murders and associated events could be potentially explained in more conventional terms.

Cinematographer Andrés Arochi does much to build the atmosphere. There are many night scenes with deep shadows and strong, contrasting pools of light. The overall colour palette is somewhat muted but white and red are used vividly. As a result the viewer is kept absorbed by the film’s aesthetic and it doesn’t immediately become apparent that this is a modest budget production with only a handful of characters. There are sufficient jump scares and a couple of scenes of jolting violence, to keep the audience's appetite sated for the staples of the horror genre. The film’s ending is as you would expect, given what has proceeded. Yet despite the series of murders and the implications of direct, satanic intervention, the film still feels restrained in its scope and doesn’t quite have the impact of a cinematic event that some claim it to be. However, less can be more and Longlegs is definitely superior to mainstream horror fare. Osgood Perkins is also a director to keep an eye on.

The Final Conflict (1981)

As a rule, it is always a challenge to end a trilogy of films successfully. Writing a satisfying denouement to a standalone movie is hard enough. To be able to conclude all pertinent story arcs and themes that have been sustained over three feature films, to everyone’s liking is far harder to achieve. In the case of The Final Conflict (1981), the last instalment of The Omen trilogy, writer Andrew Birkin does manage to resolve all of the external, internal and philosophical stakes, which are the fundamental components of a cinematic screenplay. Unfortunately, it is done in an incredibly underwhelming manner, which left audiences feeling cheated. The last time good defeated evil evil in such an unspectacular fashion was in Hammer’s To the Devil a Daughter (1976). This is why, in spite of solid production values, The Final Conflict is the least popular of the films about the Antichrist, Damien Thorn.

As a rule, it is always a challenge to end a trilogy of films successfully. Writing a satisfying denouement to a standalone movie is hard enough. To be able to conclude all pertinent story arcs and themes that have been sustained over three feature films, to everyone’s liking is far harder to achieve. In the case of The Final Conflict (1981), the last instalment of The Omen trilogy, writer Andrew Birkin does manage to resolve all of the external, internal and philosophical stakes, which are the fundamental components of a cinematic screenplay. Unfortunately, it is done in an incredibly underwhelming manner, which left audiences feeling cheated. The last time good defeated evil evil in such an unspectacular fashion was in Hammer’s To the Devil a Daughter (1976). This is why, in spite of solid production values, The Final Conflict is the least popular of the films about the Antichrist, Damien Thorn.

Damien Thorn (Sam Neill), is now 32 years old and head of his late uncle's international conglomerate, Thorn Industries. The US president appoints him Ambassador to Great Britain, which Thorn reluctantly accepts on the condition he also becomes head of the UN Youth Council. Thorn moves to the UK and continues his international scheming. However, an alignment of the stars heralds the Second Coming of Christ who, according to scripture, is to be born in England. Thorn subsequently orders all boys in the country born during the alignment to be killed. Meanwhile, Father DeCarlo (Rossano Brazzi) and six other priests recover the seven daggers of Megiddo, the only holy artefacts that can kill the Antichrist. They seek to hunt Thorn in the hope of killing him before he can destroy the Christ-child. But when the first assassin attempt goes awry, Thorn becomes aware of their plans.

The Final Conflict benefits greatly from the casting of Sam Neil as Damien Thorn. He is suitably charming and brooding. Filmed mainly in the UK, the production values are high and the film uses such locations as Cornwall and North Yorkshire extremely well. The cinematography is handled by Phil Meheux and Robert Paynter, who were both stalwarts of the UK film industry at the time. Jerry Goldsmith’s score is magnificent and does much of the heavy lifting, adding a sense of gravitas and gothic dread. The screenplay includes some bold ideas with themes of political manipulation by Thorn industries, as they create the very environmental disasters that they subsequently supply aid to. Director Graham Baker does not shy away from the infanticides ordered by Damien Thorn. Although not explicit, it is a disturbing aspect of the story.

Yet, despite so many positive points, The Final Conflict runs out of steam after the first hour. Too many good ideas are not developed sufficiently. The international intrigue alluded to at boardroom level, takes place off screen. The film would have been substantially improved if we saw directly Damien Thorn travelling the world and engaging with refugees and becoming a champion of the people. Including international locations would have better conveyed his global reach. Damien also doesn’t get to spar with his adversary. Instead he berates and harangues Christ via a rather disturbing full size crucifix that he keeps locked in an attic. Perhaps the biggest mistake the film makes is with the extravagant and contrived set pieces that befall those who discover Damien Thorn’s true nature. These had become a hallmark of the franchise. The first two onscreen deaths work well but the rest fall somewhat flat and simply aren’t shocking enough. As for ending, it serves its purpose but nothing more.

Overall, The Final Conflict is a well made but disappointing conclusion to what was originally a very intriguing franchise. Perhaps with a larger budget and a broader narrative scope that made the story more international, it could have fulfilled its potential. It certainly should have been more ambitious with its death scenes as its two predecessors were. Sadly instead of a decapitation with a sheet of glass or bisection by a lift cable, we have to make do with a high fall from a viaduct and a couple of stabbings. And then there’s the underwhelming ending. The more you think about it, the more you wonder how the studio thought this would be an appropriate ending. As it stands, The Final Conflict is watchable but offers nothing more than a perfunctory ending to the story of the rise and fall of Antichrist, Damien Thorn. Adjust your expectations accordingly.

No Blade of Grass (1970)

During the seventies, the growing environmental concerns of the general public were beginning to appear as plot themes in both mainstream and independent film making. The science fiction genre proved the most practical medium for this with films such as Zero Population growth and Soylent Green. Cornel Wilde’s No Blade of Grass takes a different approach using an ecological disaster as the premise for a survival movie. As with Wilde’s previous movies The Naked Prey and Beach Red, the message is delivered clearly and with all the subtlety of a kick in the groin. Yet the director’s honesty carries weight as he boldly depicts how the trappings of modern civilisation are quickly stripped away in the face of impending disaster. Perhaps it was this candour that upset sections of the viewing public, who didn’t wish to confront the fragility of their own society or dwell upon their own potential for violence. Certainly the film’s distributor MGM were sufficiently bothered by what they saw, that they re-edited the movie prior to release to tone down some of the stronger content.

During the seventies, the growing environmental concerns of the general public were beginning to appear as plot themes in both mainstream and independent film making. The science fiction genre proved the most practical medium for this with films such as Zero Population growth and Soylent Green. Cornel Wilde’s No Blade of Grass takes a different approach using an ecological disaster as the premise for a survival movie. As with Wilde’s previous movies The Naked Prey and Beach Red, the message is delivered clearly and with all the subtlety of a kick in the groin. Yet the director’s honesty carries weight as he boldly depicts how the trappings of modern civilisation are quickly stripped away in the face of impending disaster. Perhaps it was this candour that upset sections of the viewing public, who didn’t wish to confront the fragility of their own society or dwell upon their own potential for violence. Certainly the film’s distributor MGM were sufficiently bothered by what they saw, that they re-edited the movie prior to release to tone down some of the stronger content.

Based on John Christopher’s novel The Death of Grass published in 1956, No Blade of Grass starts with a new strain of virus that has devastated the rice crops in Asia causing a major regional famine. Soon a mutation appears in Europe infecting all types of grasses including all grain crops. The subsequent food shortages rapidly lead to social disorder, looting and possibly even cannibalism. The UK parliament start to consider desperate measures to cope with the situation. Architect and war veteran John Custance (Nigel Davenport) decides to flee London along with his wife Ann (Jean Wallace), young son Davey, teenage daughter Mary (Lyn Fredrick) and her scientist boyfriend Roger Burnham (John Hamill). They intend to travel to Westmorland in Cumbria where John's Brother, David (Patrick Holt), has a farm. Many trials and tribulations beset them as they travel north and the group quickly find themselves having to adapt both physically and morally to a rapidly changing and hostile world.

John Custance is an archetypal alpha male and embodiment of the British officer class. He is pragmatic and is quick to adapt to the deteriorating situation. But he has moral and ethical limits. So when he forms a curious relationship with a young man called Pirrie (Anthony May), it is for a very specific reason. Pirrie is a sociopath who will happily turn a gun on anyone that impedes the ongoing plan. John determines he’s a necessary tool who can do some tasks that he may balk at. This becomes very clear when we first meet Pirrie at the local gun shop where he works. He doesn’t hesitate to shoot his boss and throw in his lot with John Custance when he learns of his plan to leave London. It is this initial instance of lawlessness that marks the families rapid moral decline. Later, after having been robbed themselves, the Custance family kill a couple in a farmhouse who refuse to give them shelter. “We have to fight to live, do you understand that?” John tells his young son and his friend. “Like the Westerns?” one replies. “Yes, like that”.

No Blade of Grass is very heavy handed with its themes and moral pronunciations. At the start of the film, the affluent dine in a restaurant while a news report on TV shows the realities of the ongoing famines elsewhere in the world. There are montages of stock footage showing pollution and sick animals to hammer home the message that this is a self-inflicted catastrophe. But like the director’s other films there is an earnestness to the proceedings. Sadly this gets somewhat lost in along the way due to the film’s exploitation trappings. There are numerous shootouts between civilians and the Army as well as other acts of violence. And then there’s a gratuitous double rape. The movie even manages to include footage of a real childbirth before a climactic battle between our group of survivors and a motorcycle gang, complete with Viking helmets. Wilde also uses flashforwards as well as flashbacks, colour filters and slow motion to make his point. There is even a bleak but charming folk song performed by Roger Whittaker that plays over the start and end credits.

Violence is a reoccurring theme in all of Cornel Wilde’s films. As a director he often depicts that violence is key to survival and can galvanise people into action to forge something greater. However it can also lead to self-destruction and comes at a cost. John Custance learns that there is a price to pay for collaborating with the likes of Pirrie and that often manifests itself as human collateral damage. Social collapse and the realities of returning to a neo-feudal existence do not seem to be compatible with John’s old-world principles and ideals. His attempts to “preserve the heritage of man’s greatness” bear little fruit at the end of the film. He secures a safe place to live in the remote North of England but it takes a great deal of slaughter to do so. Furthermore the motley group of survivors he picks up along the way still harbour all the flaws of the old world, such as racial prejudice, greed and notions of exceptionalism. No Blade of Grass is a clumsy and somewhat lurid piece of film making. It certainly won’t be to everyone’s taste yet it is an interesting curiosity.

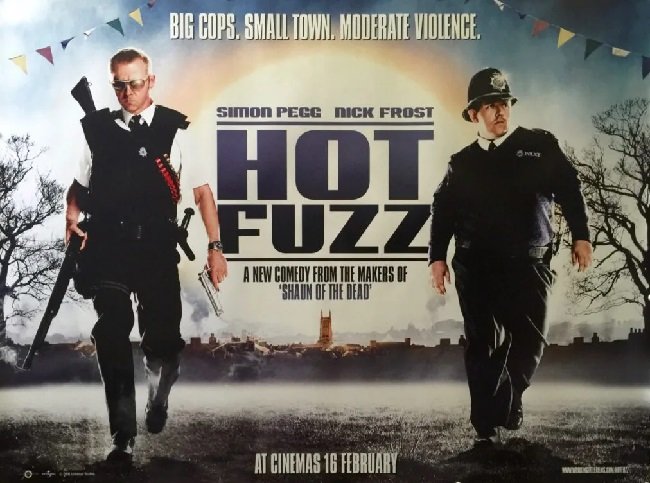

Hot Fuzz (2007)

PC Nicholas Angel (Simon Pegg) is an exemplary Police Officer, with a strict adherence to the letter of the law. As a result of making the rest of the London Metropolitan Police look bad, he is transferred to the rural town of Sandford, Gloucestershire. On arrival, Angel finds that the local Inspector, Frank Butterman (Jim Broadbent), takes a far more laissez-faire approach to policing. His colleagues are incompetent and he is further hampered by the Neighbourhood Watch Alliance (NWA), who prioritise low crime statistics over law enforcement due to their desire to win the title of “Village of the Year”. Furthermore, Angel is partnered with the Inspector’s son, Constable Danny Butterman (Nick Frost), who is infatuated with “buddy cop” movies and is in awe of Angel’s London experience. “Have you ever fired two guns while jumping through the air?” However, a sudden spate of grisly accidents lead Angel to believe that there's more to the seemingly tranquil and picture-perfect community than meets the eye.

PC Nicholas Angel (Simon Pegg) is an exemplary Police Officer, with a strict adherence to the letter of the law. As a result of making the rest of the London Metropolitan Police look bad, he is transferred to the rural town of Sandford, Gloucestershire. On arrival, Angel finds that the local Inspector, Frank Butterman (Jim Broadbent), takes a far more laissez-faire approach to policing. His colleagues are incompetent and he is further hampered by the Neighbourhood Watch Alliance (NWA), who prioritise low crime statistics over law enforcement due to their desire to win the title of “Village of the Year”. Furthermore, Angel is partnered with the Inspector’s son, Constable Danny Butterman (Nick Frost), who is infatuated with “buddy cop” movies and is in awe of Angel’s London experience. “Have you ever fired two guns while jumping through the air?” However, a sudden spate of grisly accidents lead Angel to believe that there's more to the seemingly tranquil and picture-perfect community than meets the eye.

Hot Fuzz, co-written and directed by Edgar Wright, is at first glance a satire on the buddy cop and action genres that dominated Hollywood during the eighties and nineties. Upon closer scrutiny, it also has wry takes on the Agatha Christie “whodunit”, folk horror and slasher movies. Thematically, there are references, asides and homages to such classic films as Dirty Harry, The Wicker Man and multiple John Woo titles. Stylistically, Hot Fuzz uses many visual techniques common in the work of director Tony Scott. Edgar Wright cleverly takes these elements and effectively uses them in the incongruous setting of a rural UK town. It is the depiction of these US and Hong Kong action movie tropes through the lens of British comedy with its uniquely dry perspective that makes these conceits work so well.

Hot Fuzz is bolstered by an excellent cast of UK character actors, such as Timothy Dalton, Edward Woodward and Billie Whitelaw, many of whom are sending up former roles they are well known for. Dalton particularly relishes his role as a moustache twirling villain who runs the town’s supermarket. There is also a very clear chemistry between Simon Pegg and Nick Frost which helps them navigate the clever and knowing script. The humour is broad, including slapstick, wordplay and dark satire. Yet despite its tongue in cheek nature, the film manages to tread that fine line between homage and plagiarism. There is also a very intelligent score by David Arnold, that draws on the established overwrought idiom of the action genre.

Peter Jackson uncredited cameo

Due to the amount of detail found in Hot Fuzz, the film holds up well to multiple viewings. Pausing playback to read a sign in a shop window or some other minor detail will often yield a hidden gag. Sadly, the frenetic editing and the hand cranked camera work do become somewhat tiresome after a time. The film’s two hour running time could have been tightened to something ten minutes shorter. Due to the ubiquitous nature of the action movie genre, Hot Fuzz is just a little too on the nose at times, hence it doesn’t quite hit the mark as assuredly as Wright’s previous film, Shaun of the Dead. However, these are minor quibbles. If you’re in the market for a film somewhere between the Bad Boys franchise and Inspector Morse, then Hot Fuzz has much to offer. A convoluted plot, a cast shamelessly sending themselves and the genre up, car chases, shootouts and so many throw away lines. “He’s not Judge Judy and executioner”.

Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1983)

Halloween III: Season of the Witch is a film that often provokes a strong reaction from genre fans. This is mainly due to it not having any direct connection to the previous two films. The absence of Michael Myers in such a franchise was a serious mistake and the subsequent poor box office returns endorsed this. Yet if this film had been released as a separate product it may not have performed so poorly. After re-examining Halloween III: Season of the Witch there are many aspects of interest. Despite a troubled production, the film is an intriguing anomaly that tried to be different during a decade where the established horror formula was “stalk n' slash”. It does have a very bleak tone and some consider it to be mean spirited as the cast are killed off one by one. Perhaps theme of child sacrifice caused audiences to balk?

Halloween III: Season of the Witch is a film that often provokes a strong reaction from genre fans. This is mainly due to it not having any direct connection to the previous two films. The absence of Michael Myers in such a franchise was a serious mistake and the subsequent poor box office returns endorsed this. Yet if this film had been released as a separate product it may not have performed so poorly. After re-examining Halloween III: Season of the Witch there are many aspects of interest. Despite a troubled production, the film is an intriguing anomaly that tried to be different during a decade where the established horror formula was “stalk n' slash”. It does have a very bleak tone and some consider it to be mean spirited as the cast are killed off one by one. Perhaps theme of child sacrifice caused audiences to balk?

A mysterious patient, Harry Grimbridge (Al Berry) is brought to hospital late at night, after being pursued by several besuited assassins. He is subsequently murdered in his bed and his assassin then kills himself. Dr. Dan Challis (Tom Atkins) is shocked by these events and struggles to comfort Ellie Grimbridge (Stacey Nelkin), the victims daughter who arrives at the hospital seeking answers about her father's death. The pair decide to investigate matters and the trail leads to the town of Santa Mira. Harry, who ran a toy shop, had travelled to the town to collect a shipment of Halloween masks from Silver Shamrock Novelties. On arrival Dan and Ellie find the town dominated by the presence of the Silver Shamrock company and its charismatic owner Conal Cochran (Dan O'Herlihy). Is Cochran connected to the death of Ellie's Father? Who are the mysterious mute assassins in grey suits that are pursue them?

John Carpenter, although only a producer on this film, was still heavily involved in the film’s development. Being a big fan of British writer Nigel Kneale, he commissioned him to write a screenplay. However the final draft did not find favour with financier Dino De Laurentiis, who insisted in the inclusion of more graphic death scenes to placate the target demographic. Kneale subsequently had his name removed from the credits but most of his original material remained in the redrafted screenplay, such as his re-occurring theme of reconciling science and witchcraft. It is paradoxical how Cochran uses contemporary technology to perpetrate an act of pagan sacrifice. The film also draws heavily on the 1956 genre classic Invasion of the Bodysnatchers, with its themes of humans being replaced by a sinister intelligence. The Silver Shamrock factory is set in the fictitious town of Santa Mira, which also features in Don Siegel's movie.

As for the scenes of violence, they are themselves quite unusual. Although gory to a degree, they are also a little surreal. Veteran make-up artist Tom Burman creates several bizarre deaths that reflect the odd nature of the plot. A man is murdered in his hospital bed by having his skull broken. Another has his head pulled off. But the most effective are those caused by the booby trapped Halloween masks. The demise of a particularly unpleasant small boy, involving cockroaches and snakes is both ghoulish and satisfying. The atmosphere and tone of the film is bolstered by an outstandingly minimalist score by John Carpenter and Alan Howarth. There is also an excellent faux commercial for Silver Shamrock masks which is both infuriating and an earworm.

The film also benefits from earnest performance from its main cast. Due to budgetary reasons the leads were character actors and not box office stars. Genre favourite Atkins acquits himself well as the world weary Doctor. But it is Dan O'Herlihy who excels as the sinister head of Silver Shamrock. His soft voice and measured delivery adds weight to the plot and the motives of a man who wishes to punish a nation through the death of it children. He delivers a singularly sinister monologue at the film’s denouement. Director Tommy Lee Wallace (who also directed Halloween II) maintains the tension and imbues the town of Santa Mira with a unsettling quality. He also handles the blending of pagan themes with modern technology well.

Despite its initial failure, over the recent years Halloween III: Season of the Witch has been re-appraised by critics and developed the inevitable cult following. It is seen as a social comment on consumerism and commercialisation. It also explores the roots of a Pagan festival that has now become an integral part of US culture. The bleak ending that was somewhat unpalatable 25 years ago, is now credible to a postmodern audience. John Carpenter was happy to lay Michael Meyers to rest permanently after Halloween II and wanted the subsequent films in the series to be wider in vision, dealing each time with a different supernatural theme. Such a bold idea was not endearing to the prevailing studio mentality of the time. Thus after the box office failure of Halloween III: Season of the Witch, the overall concept was side-lined and "the shape" subsequently resurrected in future sequels.

Event Horizon (1997)

Event Horizon is a curious movie hybrid, mixing plot elements from classic sci-fi and horror genres. It has been labelled “Hellraiser in Space” by some lazy critics, although I think there's far more to it than that. Perhaps a more apt description would be a Gothic horror story set in space. The movie has garnered a cult reputation since its release in 1997, mainly due to its graphic imagery and troubled production history. It does indeed have some quite shocking sequences but the lightning editing does not show as much as some would think. Paramount forced director Paul W S Anderson to reduce the original one hundred and thirty minute running time down to a more manageable ninety, after unfavourable test screenings. Much of the violence was allegedly removed as a result of that process. Sadly nothing survives of the removed material other than a VHS workprint. Hence a restored director’s cut is therefore unlikely.

Event Horizon is a curious movie hybrid, mixing plot elements from classic sci-fi and horror genres. It has been labelled “Hellraiser in Space” by some lazy critics, although I think there's far more to it than that. Perhaps a more apt description would be a Gothic horror story set in space. The movie has garnered a cult reputation since its release in 1997, mainly due to its graphic imagery and troubled production history. It does indeed have some quite shocking sequences but the lightning editing does not show as much as some would think. Paramount forced director Paul W S Anderson to reduce the original one hundred and thirty minute running time down to a more manageable ninety, after unfavourable test screenings. Much of the violence was allegedly removed as a result of that process. Sadly nothing survives of the removed material other than a VHS workprint. Hence a restored director’s cut is therefore unlikely.

Event Horizon is an experimental spaceship which went missing on its maiden voyage. When the ship mysteriously reappears in orbit above Neptune, a rescue mission is launched by the authorities. The ship's designer Dr. Weir (Sam Neil) is assigned to the rescue vessel Lewis and Clark, commanded by Captain Miller (Laurence Fishburne). The crew consists of Lieutenant Starck (Joely Richardson), pilot Smith (Sean Pertwee), Medical Technician Peters (Kathleen Quinlan), Engineer Ensign Justin (Jack Noseworthy), Rescue Technician Cooper (Richard T. Jones), and Trauma Doctor D.J. (Jason Isaacs). Upon arrival they find that the Event Horizon is empty and the crew dead or missing. The ship's last transmission contains human screams and a cryptic message in Latin. Subsequently the rescue party starts experiencing horrific hallucinations along with a growing sense that unease.

There are many positive aspects to Event Horizon. The cast of character actors are more than competent and the production values are very high. The sets are opulent and the production design conveys the required hi-tech aesthetic. The visual effects have not dated too much although some of the CGI is a little primitive. The prosthetics and animatronics are exceedingly good (and unpleasant). Bob Keen and his creative team were involved in the production although much of their work unfortunately didn't make it into the theatrical version. The movie also manages to maintain a disquieting atmosphere, punctuated by some effective jumps. Sadly the screenplay lurches from the good to the bad and is somewhat inconsistent. The denouement does succeed in explaining the evil entity that is linked to the ship but I would have preferred some further insight. However these narrative inconsistencies may be due to the last minute re-edit that took place prior to release.

However despite these issues, Event Horizon is sustained by its ambition, tone and grotesque visuals. Director Paul W S Anderson has produced a tense and atmospheric blend of genres, despite the studio's interference in post-production. The mixing of advanced technology with Hieronymus Bosch style visions of Hell are quite compelling. Certainly the movie deserves more critical praise than it gained upon release in 1997. It’s a shame that a restored cut of the film is off the table. It would be most interesting to see the gaps in the narrative filled, as well as the visual effects restored to their full glory. Clive Barker managed to achieve a comparable restoration of his movie Nightbreed, which was similarly “butchered” upon release. However, unless the missing material can be miraculously sourced from elsewhere, the theatrical edition of Event Horizon will remain the only version available.

The Car (1977)

The peace of tranquillity of Santa Ynes, Utah, is shattered when the town becomes the focus of several hit and run deaths, by a mysterious and apparently driverless, black car. After the Sheriff (John Marley) is run down, it is down to Captain Wade Parent (James Brolin) and his deputies to protect the town from this sinister threat. Is the car simply a driven by a mad man or is there a more supernatural explanation? When the car menaces a local school marching band, the teachers and students take refuge in the nearby cemetery. Does the cars inability to enter consecrated ground provide a clue to its otherworldly origins and offer a potential solution? As the death count increases and the population becomes more fearful, the Captain and his team of deputies form a desperate plan to see if they can lure the car into a trap.

The peace of tranquillity of Santa Ynes, Utah, is shattered when there are several hit and run deaths by a mysterious and apparently driverless, black car. After the Sheriff (John Marley) is run down, it is down to Captain Wade Parent (James Brolin) and his deputies to protect the town from this sinister threat. Is the car simply a driven by a mad man or is there a more supernatural explanation? When the car menaces a local school marching band, the teachers and students take refuge in the nearby cemetery. Does the cars inability to enter consecrated ground provide a clue to its otherworldly origins and offer a potential solution? As the death count increases and the population becomes more fearful, the Captain and his team of deputies form a desperate plan to see if they can lure the car into a trap.

A movie like The Car needs something else other than its initial premise to keep it going. To provide it with narrative impetus and keep the viewer engaged. Simply put, if the audience is to spend ninety or so minutes watching a group of people in peril then it needs to be able to relate and empathise with them. Surprisingly, that is exactly what director Elliot Silverstein does. Having cut his teeth directing several episodes of The Twilight Zone, he has a good sense of pace and how to build the tension leading up to the “boo” moment. The Car has a solid cast of respectable characters actors and actually makes a decent attempt to try and provide some backstory and sub plots. There is a genuine feeling that this is a real small town. There’s the ex-drunk officer, the wife beater and a lead character living in his father’s shadow. John Marley is good as a sheriff whose world is turned upside down by the arrival of this potentially satanic car. You feel that he genuinely cares.

As ever with movies of this ilk, the low budget means that the scope of action is somewhat restricted. Yet the various death scenes in which innocent members of the public are run down are well constructed with the focus upon tension rather than gore. The Car taps into similar themes as Steven Spielberg’s Duel, with its exploration of our fear of the motor vehicle, its associated anonymity and potential to kill. In one scene the car drives right through a victim’s house to kill them, shattering the presumption that once off the road, you are safe. Certainly fusing the road movie genre with the supernatural was a bold idea. It works better here than in similar films such as Race with the Devil. But one cannot discuss The Car without referencing the customised 1971 Lincoln Continental Mark III designed by George Barris. It is in many ways the real star of the movie, having a genuine presence and posing a credible threat.

The Night Flier (1997)

The key to success in the horror genre is to try and find an innovative new angle on tried and tested themes and tropes. The Night Flier is an often-overlooked gem, that takes a unique perspective on vampirism and features strong performances as well as an intelligent and thoughtful screenplay. It builds a sense of foreboding during it’s first two acts and teases audiences with some unpleasant prosthetic effects, courtesy of KNB EFX Group. The climax of the movie is both thought provoking and suitably unpleasant. Furthermore, The Night Flier even manages to make a coherent criticism of tabloid culture and morals of those journalists working in the industry. It’s a damn shame that this modest but well-crafted genre movie didn’t get the attention it deserved when it was initially released in 1997.

The key to success in the horror genre is to try and find an innovative new angle on tried and tested themes and tropes. The Night Flier is an often-overlooked gem, that takes a unique perspective on vampirism and features strong performances as well as an intelligent and thoughtful screenplay. It builds a sense of foreboding during it’s first two acts and teases audiences with some unpleasant prosthetic effects, courtesy of KNB EFX Group. The climax of the movie is both thought provoking and suitably unpleasant. Furthermore, The Night Flier even manages to make a coherent criticism of tabloid culture and morals of those journalists working in the industry. It’s a damn shame that this modest but well-crafted genre movie didn’t get the attention it deserved when it was initially released in 1997.

Jaded and cynical tabloid reporter Richard Dees (Miguel Ferrer) initially refuses the job of investigating a violent murder at a remote private airfield. So his boss and editor of Inside View (a National Enquirer style publication), Merton Morrison (Dan Monahan), assigns the case to rookie reporter Katherine Blair (Julie Entwisle). When it becomes apparent that there is a serial killer using the network of small, rural airfields and flying under the alias of Dwight Renfield, Dees takes over the assignment. However, Morrison asks Katherine to follow Dees as he’s grown tired of his ego and insubordination. As Dees uncovers more information regarding “The Night Flier”, he starts receiving warnings from the killer himself to stop his investigations. It soon becomes clear that there may well be more to the case than meets the eye and that Dwight Renfield is not a mere serial killer but a vampire.

There are several standout aspects of The Night Flier. The first and most important is the strong lead performance by the late Miguel Ferrer who excels as the journalist Richard Dees. Exactly what is his motivation beyond doing whatever is needed to get the story, is left intriguingly vague. Dees is a bitter and heartless character, but he’s driven and surprisingly good at what he does. Then there’s the intriguing use of the network of small, private airfields that exist across North America and the entire sub-culture of having a pilot’s license. It’s an aspect of life that is unknown to many people. And then there’s our undead antagonist, Dwight Renfield. There’s a fine line between being vague and insubstantial, compared to creating a sense of the enigmatic and uncanny. Yet director Mark Pavia manages to tread such a path, providing only a smattering of implied history for the villain of the piece, while maintaining our interest rather than indifference.

Overall, The Night Flier is a good and faithful adaptation of Stephen King’s novella with the only major creative difference being the bleaker ending adopted for the movie. It serves not only as a fitting and inevitable conclusion to the story arc, but also as an acerbic indictment upon the iniquities of tabloid journalism. All of which leaves Richard Dees philosophy on journalism ringing in one’s ears. "Never believe what you publish and never publish what you believe". Twenty-six years on from its initial release, word of mouth and a revised critical assessment means that The Night Flier is finally reaching a wider audience. In a world filled with so many poor and indifferent adaptations of Stephen King’s work, this “diamond in the rough” is an entertaining and engaging alternative and worth the time of discerning horror fans.

Dr. Terror's House of Horrors (1965)

Dr. Terror's House of Horrors was the first portmanteau horror movie by Amicus Productions. The small British studio was founded by producers and screenwriters Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg. As the horror genre grew in popularity due to the success of Hammer films, Amicus saw the potential in the portmanteau format. Subotsky in particular held Ealing Studios 1945 classic Dead of Night in very high regard. Although only a modest budget movie, Dr. Terror's House of Horrors proved to be financially successful and led to a series of similarly structured films over the next decade. These included Torture Garden (1967), The House That Dripped Blood (1970), Asylum (1972), Tales from the Crypt (1972), The Vault of Horror (1973), From Beyond the Grave (1974),

Dr. Terror's House of Horrors was the first portmanteau horror movie by Amicus Productions. The small British studio was founded by producers and screenwriters Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg. As the horror genre grew in popularity due to the success of Hammer films, Amicus saw the potential in the portmanteau format. Subotsky in particular held Ealing Studios 1945 classic Dead of Night in very high regard. Although only a modest budget movie, Dr. Terror's House of Horrors proved to be financially successful and led to a series of similarly structured films over the next decade. These included Torture Garden (1967), The House That Dripped Blood (1970), Asylum (1972), Tales from the Crypt (1972), The Vault of Horror (1973), From Beyond the Grave (1974),

Set on a late night train from London to Bradley, five passengers encounter a mysterious Dr Schreck (Peter Cushing) who offers to tell each passenger their future with a deck of Tarot cards. Initially most of them are sceptical, however curiosity eventually gets the better of them. As the Dr. proceeds, each man's story plays out as a vignette plays with a suitably sinister tone. All of which inevitably end unfavourably for the protagonists. Can the five passengers possibly escape their predicted demise? Will a fifth card drawn from the deck hold the key? Each time it is the death card; a conclusion they are far from happy with or ready to accept.

The most notable aspect of Dr. Terror's House of Horrors it its strong cast of British character actors. Jeremy Kemp, Bernard Lee and stately Christopher Lee effortlessly acquit themselves. A young Donald Sutherland was secured for the benefit of selling the movie to the US market. Roy Castle and Kenny lynch add some welcome levity to one story, without derailing the atmosphere. But ultimately it is Peter Cushing as the unshaven and shabby Dr. Schreck, who dominates the proceedings. He strikes the right balance between frailty and malevolence perfectly. The sinister look he gives when the first passenger (Neil McCallum) taps the Tarot card three time shows his prodigious acting talent.

As for the five stories that unfold, The Werewolf and Disembodied Hand are perhaps the strongest and the most traditionally grounded in horror. The others make up for in style what they lack in genuine horror. The Roy Castle's Voodoo tale is quite comic and reminiscent in tone to the Golfing story in Dead of Night. The Creeping Vine in which a family home is menaced by a sentient plant is surprisingly low key (due to minimal special effects) and works better that way. Vampire sees a newlywed Doctor who discovers that his wife may be a vampire. It has a rather clever sting in the tail. The resolution of the entire film holds yet another plot twist, though I'm sure it will come as no surprise to those familiar with this genre.

Despite its modest budget, this was considered a finely crafted horror vehicle at the time and had an X certificate rating. DVD copies currently available in the UK are now rated PG by the British Board of Film Classification. However it must be remembered that the British horror genre at the time was still in a state of transition. Hammer Studios had introduced more lurid elements to the proceedings but many films involving the supernatural still tended to rely on atmosphere and tone. Hence there is an emphasis on dialogue and performances in Dr. Terror's House of Horrors over gore. The atmospheric cinematography by Alun Hume (Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi, A View to a Kill) and the use of Techniscope elevate this mainly studio based production into something more than the average horror movie.

The portmanteau format proved lucrative for Amicus, mainly due to their focus on inventive writing and their stable of regular stars. The sub-genre fell out of favour in the late seventies as Hollywood scored box office success with blockbuster horror films such as The Exorcist and The Omen. However the influence of Dr. Terror's House of Horrors left its mark and occasionally film makers still try their hand with the multi-story format. The success of George Romero's Creepshow, based upon the baroque style of EC horror comics and Stephen King's Cat's Eye prompted a resurgence of the portmanteau horror in the mid-eighties. With the industries current penchant for rebooting past successes, perhaps we'll see a return of horror compilation.

Ghost Story (1981)

Ghost Story is a deliberately superficial adaptation of the novel by Peter Straub. If you’ve read the book and are expecting a verbatim retelling of the plot, then you will be disappointed. It’s complex narrative structure and the abundance of characters do not immediately lend themselves to mainstream film making. However, if you like tales of the supernatural and solid performances from Hollywood legends, then this may well be for you. John Irvin has always been a workman like director and has therefore often been overlooked. Films such as Hamburger Hill and When Trumpets Fade show a great deal of focus and a clear understanding of the mechanics of cinema.

Ghost Story is a deliberately superficial adaptation of the novel by Peter Straub. If you’ve read the book and are expecting a verbatim retelling of the plot, then you will be disappointed. It’s complex narrative structure and the abundance of characters do not immediately lend themselves to mainstream film making. However, if you like tales of the supernatural and solid performances from Hollywood legends, then this may well be for you. John Irvin has always been a workman like director and has therefore often been overlooked. Films such as Hamburger Hill and When Trumpets Fade show a great deal of focus and a clear understanding of the mechanics of cinema.

Released in the early eighties during the peak of the slasher boom, Ghost Story fell squarely outside that sub-genre and offered the public a more traditional supernatural story. The initial intent was to produce an atmospheric movie built upon performances and suspense. Yet the studio, in their infinite wisdom, felt that there was a need for high profile shocks, so make up effects master Dick Smith was brought onboard to bring the story’s undead antagonist to the screen. Yet despite creating a broad range of ghoulish specters, much of his work never made it to the final edit. What remains is still exemplary and suitably grim, but one gets the sense that punches are being deliberatley pulled.

The plot focuses on the “Chowder Society”, an gentlemen’s club comprising of businessman Ricky Hawthorne, lawyer Sears James, Dr. John Jaffrey, and Mayor Edward Charles Wanderley. The four ageing men regularly meet, dine and swap tales of the sinister and supernatural. When Mayor Wanderley’s eldest son David falls to his death from a luxury apartment, the only clue is an enigmatic woman that he allegedly had a whirlwind romance with. David’s brother Don, soon finds himself in a similar relationship with a beautiful stranger who seems to know not only a lot about him, but the other surviving members of the “Chowder Society”. Don begins to question the woman’s identity and gradually becomes aware of a dark secret that his Father and friends are harbouring.

Ghost story is blessed with an outstanding cast comprising of John Houseman, Douglas Fairbanks Jr, Melvyn Douglas and the great Fred Astaire. They all bring a degree of dignity and gravitas to the proceedings. It is also worth noting that the actors who play the “Chowder Society” in their youth are very well matched. Alice Krige brings a suitably sinister quality to her performance and exudes malevolence. Sadly despite much promise, the screenplay by Lawrence D. Cohen is a little hit and miss in places, as is the editing. One aspect of the plot involving two human familiars in league with the vengeful spirit is never satisfactorily explained. However, as well as strong performances, Ghost Story sports handsome cinematography by Jack Cardiff and a sumptuous score by Philippe Sarde.