My Local Cinema Part 2

I last wrote about my local cinema in late October 2025. The Sidcup Storyteller had shut and the local authority, Bexley Council, was negotiating with the management of the Castle Cinema in Hackney to run the establishment. Fortunately for all, a deal was struck and the cinema re-opened just before Christmas under the new name of the Castle Sidcup. I had the pleasure of seeing Zootropolis 2 there just after New Year and enjoyed not only the film but the cosy and friendly atmosphere of the newly refurbished cinema. It is convenient to be able to see new films locally and the fact that it is one bus ride away or a leisurely walk in good weather, makes it far more likely that I will actually go to see new releases, rather than watch them at home. The Castle Sidcup also has very competitively priced ticket prices which makes it a more inviting prospect compared to the two local chain multiplexes.

I last wrote about my local cinema in late October 2025. The Sidcup Storyteller had shut and the local authority, Bexley Council, was negotiating with the management of the Castle Cinema in Hackney to run the establishment. Fortunately for all, a deal was struck and the cinema re-opened just before Christmas under the new name of the Castle Sidcup. I had the pleasure of seeing Zootropolis 2 there just after New Year and enjoyed not only the film but the cosy and friendly atmosphere of the newly refurbished cinema. It is convenient to be able to see new films locally and the fact that it is one bus ride away or a leisurely walk in good weather, makes it far more likely that I will actually go to see new releases, rather than watch them at home. The Castle Sidcup also has very competitively priced ticket prices which makes it a more inviting prospect compared to the two local chain multiplexes.

The Castle Sidcup is an independent, community-driven cinema, run by the same small team behind The Castle Cinema in Hackney. Not being part of a chain, the Castle Sidcup is striving to show a broad variety of cinematic content. This will include the best new releases, outstanding independent films as well as family favourites. There are also future plans to screen cult classics and host film clubs and special events. The management also intends to facilitate a range of accessible and community-focused screenings including baby screenings, relaxed screenings and more. The cinema also supports audio description, HoH subtitles and amplified audio. All of which is intended to make the Castle Sidcup an invaluable community asset and sounds very promising.

I am quite interested that the Castle Sidcup is available for private hire. I think it would be nice to have a screening of a classic film such as John Carpenter’s The Thing and have a few friends join me. For someone with a keen interest in cinema, that would be an excellent birthday present. There is also the potential for wider events and activities. I used to attend lots of small, independent film festivals in the eighties and nineties. Such events are less common these days and tend to be overshadowed by larger, more corporate undertakings or longstanding events that have become too commercial. I’d be interested to learn what the cost and logistics would be of putting on a Contains Moderate Peril film festival. I shall investigate accordingly. In the meantime it is reassuring to have a local cinema once again and I shall endeavour to use it more over the year ahead.

My Local Cinema

In a misguided fit of enthusiasm, I briefly considered booking tickets to go to London next month to see Predator: Badlands at the IMAX cinema at Waterloo. However, I balked at the price and when I considered the train journey and the fact I’d be going on my own, apathy got the better of me. I decided to wait until the film becomes available on Disney + etc. Hence cinema’s loss is streaming’s gain, which seems to be becoming an all too familiar story. I’ve only been to the cinema once this year and that was to the British Film Institute, where I saw an old classic, Electra Glide in Blue, rather than a new film. Last year I went to the cinema three times. All visits were to my local venue, the Sidcup Storyteller. Sadly that cinema has been closed since the end of July and its future has hung in the balance. Its absence has been keenly felt as it provided a pleasant and convenient local service.

In a misguided fit of enthusiasm, I briefly considered booking tickets to go to London next month to see Predator: Badlands at the IMAX cinema at Waterloo. However, I balked at the price and when I considered the train journey and the fact I’d be going on my own, apathy got the better of me. I decided to wait until the film becomes available on Disney + etc. Hence cinema’s loss is streaming’s gain, which seems to be becoming an all too familiar story. I’ve only been to the cinema once this year and that was to the British Film Institute, where I saw an old classic, Electra Glide in Blue, rather than a new film. Last year I went to the cinema three times. All visits were to my local venue, the Sidcup Storyteller. Sadly that cinema has been closed since the end of July and its future has hung in the balance. Its absence has been keenly felt as it provided a pleasant and convenient local service.

The Sidcup Storyteller cinema temporarily closed because its operator, Really Local Group (RLG), went into liquidation. RLG faced wider financial difficulties, which led to the closure of its venues and a temporary closure of the Sidcup cinema for a refurbishment and transition to new management. The cinema was expected to reopen under a new operator, supported by Bexley Council in September. Sadly, finding a replacement operator with the necessary experience has proven harder than expected. However, it would appear that the management team behind Hackney’s Castle Cinema are looking to run the Sidcup Storyteller, which seems very reassuring. The Castle Cinema is an independent, crowd-funded community movie theatre and not affiliated to any corporate behemoths.

As there is no timetable at present for the re-opening of the Sidcup Storyteller cinema, I shall have to look to nearby alternatives for my immediate cinematic needs. There is the Vue cinema in Eltham High Street and Cineworld in Bexleyheath Broadway. They’re not my first choice as I’ve had issues with them in the past, such as film’s being shown in the wrong aspect ratio and lighting being insufficiently dimmed. They also seem to favour the most commercially viable films to schedule. Hence you don’t always get as much choice as you would like. Plus they tend to attract younger viewers who struggle with the social etiquette associated with a trip to the cinema. Therefore, I hope that an appropriate deal can be struck between the Castle Cinema management and Bexley Council, resulting in the Sidcup Storyteller cinema re-opening its doors soon.

Five Films I Like

I was asked recently, what are my top five films of all time? This is one of those loaded questions that I don’t really like to answer. I enjoy lots of films across multiple genres. This includes acknowledged “classics” as well as low rent, exploitative trash. So why limit myself to just five films? Also, my answers would change regularly depending upon my mood and current cinematic interests. However, that doesn’t make for a pithy and interesting response to the original question. So I shall compromise. Here is a list of five films that I have an abiding love for and watch frequently. They always entertain me and there is a sense of comfort whenever revisiting them. That's not to say they are all good films. Possibly only one that is listed is considered a piece of noteworthy art. The rest are just entertaining to various degrees. Yet I have a strong emotional attachment to them all. Sometimes that’s all that matters.

I was asked recently, what are my top five films of all time? This is one of those loaded questions that I don’t really like to answer. I enjoy lots of films across multiple genres. This includes acknowledged “classics” as well as low rent, exploitative trash. So why limit myself to just five films? Also, my answers would change regularly depending upon my mood and current cinematic interests. However, that doesn’t make for a pithy and interesting response to the original question. So I shall compromise. Here is a list of five films that I have an abiding love for and watch frequently. They always entertain me and there is a sense of comfort whenever revisiting them. That's not to say they are all good films. Possibly only one that is listed is considered a piece of noteworthy art. The rest are just entertaining to various degrees. Yet I have a strong emotional attachment to them all. Sometimes that’s all that matters.

The Medusa Touch (1978)

An interesting adaptation of a popular seventies novel by Peter Van Greenaway. Novelist John Morlar is found in his flat, savagely beaten yet clinging to life. The subsequent Police investigation uncovers that Morlar has continuously encountered tragedy throughout his life and how many of those associated with him have died unexpectedly. After reading Morlar’s journals, Inspector Brunel (Lino ventura) begins to suspect that the injured novelist may be able to cause disasters. Although Richard Burton was not in the best of health when he made this film, he still delivers a powerful and charismatic performance as a misanthropic author. There is some eminently quotable dialogue and the tension steadily builds to a dramatic climax. The cathedral collapse at the end of the film is very well realised with practical effects and miniatures. The Medusa Touch is also a who's who of British character actors of the time.

Journey to the Far side of the Sun AKA Doppelgänger (1969)

This British science fiction film was produced by Gerry and Sylvia Anderson at the height of their success. However, one of Universal Studios financing requirements was that the film had to be directed by an established American director. Hence Robert Parrish got the job and clashed with Gerry Anderson. As a result many subplots within the script were cut from the final film. As a result the story, although intriguing and very akin to an episode of the Twilight Zone, struggles to sustain the film’s 100 minute running time. However the production design is stylish and in a very late sixties idiom. There's a sumptuous score by Barry Gray and the miniature effects by Derek Meddings are sublime. Especially the rocket launch. As ever with Gerry Anderson there is a casual and tonally unexpected use of violence and the film has a wonderfully bleak ending that no studio would countenance these days.

Krull (1983)

This hybrid fantasy movie started as sword and sorcery film but subsequently morphed into a Star Wars clone during its pre-production in a curious attempt to hedge its bet. At the time this was a very expensive movie using multiple sound stages at Pinewood Studios and location filming in both Spain and Italy. Krull is narratively and thematically somewhat of a mess due to the obvious changes made to the screenplay. However, it looks fantastic and features a wonderful cast of such character actors as Freddie Jones, Alun Armstrong and the great Bernard Bresslaw. There are also early appearances by Liam Neeson and Robbie Coltrane. Krull has developed quite a cult following over time. The Slayers and the Beast designs are quite scary and there is a superb score by James Horner that is very reminiscent of the halcyon Hollywood days of Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Miklós Rózsa.

Raise the Titanic (1980)

British media proprietor and impresario Lew Grade fared very well in television throughout the sixties and seventies. However, he was not so successful when he moved into film production. Raise the Titanic, based upon the novel by Clive Cussler, went through dozens of re-writes before it went into production, which accounts for why the final screenplay is so indifferent. The cast is curious and you get the impression that everyone they originally wanted was not available. Yet those actors who were eventually cast, Richard Jordan, Jason Robards and Alec Guiness are perfectly competent. However, the film was critically panned and bombed at the box office, effectively ruining ITC Productions. Irrespective of this, the miniature effects are outstanding and John Barry's portentous score does much of the heavy lifting, creating atmosphere, mystery and intrigue. It’s not a hidden gem but Raise the Titanic is far from the dog’s dinner some claim.

Night of the Demon AKA Curse of the Demon (1957)

Based on M R James' short story Casting the Runes, this is a horror masterpiece from director Jacque Tourneur. Beautifully shot in black and white by Ted Scaife, the film boasts an excellent production design by Ken Adam who subsequently went on to create all the huge sets for the sixties and seventies Bond films. The implied horror and tension is superbly handled and when the demon turns up it is suitably grim, despite its technical limitations. It was originally intended that the demon would be created by stop motion legend Ray Harryhausen but he was sadly unavailable. The optical smoke effects by FX wizard Wally Veevers are a marvel and were subsequently repeated in his last film The Keep in 1983. Night of the Demon is a bonafide horror classic due to its attention to detail and palpable atmosphere. Again a strong cast, including Dana Andrews, Peggy Cummings and Niall MacGinnis contributes substantially to the proceedings.

Theatrical Version or Director's Cut?

Not all film director’s have the luxury of “final cut”. The right to ensure that the completed version of a film corresponds with their creative vision. Films are commercial undertakings and sometimes the producers, film studio or other interested parties get to assert their wishes over that of the director. Often this can be due to practical considerations such as running time or budget. On occasions, this can be down to major creative and artistic differences. Hence the theatrical release of a film may be considered flawed, unfinished or just plain wrong by the director, if changes have been imposed, regardless of the reasons. Therefore, a director’s cut of a film can offer a significantly different cinematic vision over the original theatrical release. They can present an opportunity to fix perceived problems or just put more narrative meat on the bones. This may lead to a film being critically reappraised.

Not all film director’s have the luxury of “final cut”. The right to ensure that the completed version of a film corresponds with their creative vision. Films are commercial undertakings and sometimes the producers, film studio or other interested parties get to assert their wishes over that of the director. Often this can be due to practical considerations such as running time or budget. On occasions, this can be down to major creative and artistic differences. Hence the theatrical release of a film may be considered flawed, unfinished or just plain wrong by the director, if changes have been imposed, regardless of the reasons. Therefore, a director’s cut of a film can offer a significantly different cinematic vision over the original theatrical release. They can present an opportunity to fix perceived problems or just put more narrative meat on the bones. This may lead to a film being critically reappraised.

However, it is erroneous to assume that a director’s cut is a superior version of a film by default. Sometimes, a filmmakers desire to return to a previous project and make alterations yields no significant results. Some director’s even develop a reputation as “serial tinkerers” who never seem to be satisfied, whatever the results. Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now exists formerly in three distinct versions. Oliver Stone has released four versions of his film Alexander (2004). As for George Lucas, he stated in an interview that “films are never completed, they’re only abandoned”. He has famously revisited his body of work several times and not necessarily to their overall benefit. With all this in mind, here are three films, where popular opinion and critical acclaim favours the original theatrical version over the later released director’s cut.

Alien (1979). Ridley Scott is another well known director who always seems to revisit his work and make alterations. His reasons for re-editing vary and sometimes they do yield better movies. However, the original theatrical release of Alien is described by Scott himself as “the best he could possibly have made at the time”. Yet in 2003, he released a “director’s cut” despite stating that this was not his definitive version. The new version restored roughly four minutes of deleted footage, while cutting about five minutes of other material, leaving it approximately a minute shorter than the theatrical cut. The standout changes were to Brett’s death scene which shows more of the xenomorph and the infamous scene where Ripley finds Dallas “cocooned” and puts him out of his misery. Being no more than a fan service, this version has no additional value. In fact it can be argued that it only serves to contradict the xenomorph’s established biology.

Donnie Darko (2001). Richard Kelly had to compromise when making his off kilter science fiction movie. The main one being keeping the running time below two hours. In 2004, director Kelly, re-cut the film, added twenty minutes of previously deleted footage as well as new music and sound effects. This director's cut provides a clearer insight into many of the film's more ambiguous plot elements and makes the previously vague temporal mechanics less esoteric. However, critics and fans alike have stated that the charm of the theatrical release lies in its mysterious and ill defined nature. It is a deliberately enigmatic cinematic journey. Kelly’s second edit may well add clarity but in doing so neuters what so many viewers found endearing. Sometimes, less is indeed more.

The Warriors (1979). Walter Hill’s underrated, stylised gang drama has its roots in the writings of ancient Greek professional soldier Xenophon. The theme of a group of warriors trapped in hostile territory and trying to get home is cleverly transposed to seventies New York City. Made on a tight schedule by a studio that wasn’t especially enamoured with the material, Hill didn’t get to draw the exact parallels he originally wanted. Hence in 2005, he added a new opening scene with a voiceover describing how Xenophon’s army attempted to fight its way out of Persia and return home. He also inserted comic-book splash panel shots as a means to bridge various key scenes in the film. Sadly, this was a little too on the nose and too expository. Recent releases of The Warriors on Blu-ray and UHD have included both versions and the consensus remains that the theatrical release is more efficient, requiring no further embellishment.

Broadening Your Cinematic Horizons

I haven’t been to the cinema since December 2019 when I saw the last Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker. Increasing ticket prices, along with the pandemic have kept me away. But perhaps the biggest contributory factor to my ongoing cinematic abstinence has been just a lack of interesting films being released. My local multiplex has become a platform for mainly big cinematic franchises. Compared to the seventies and eighties, there is considerably less choice regarding the types of films being shown. I am not saying that a broad variety of films are no longer being made, because that is not the case. What has changed is the medium by which we view them. Human dramas, art house films, comedies and many other genres that don’t command major box office taking are no longer being shown theatrically and are finding a home elsewhere.

I haven’t been to the cinema since December 2019 when I saw the last Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker. Increasing ticket prices, along with the pandemic have kept me away. But perhaps the biggest contributory factor to my ongoing cinematic abstinence has been just a lack of interesting films being released. My local multiplex has become a platform for mainly big cinematic franchises. Compared to the seventies and eighties, there is considerably less choice regarding the types of films being shown. I am not saying that a broad variety of films are no longer being made, because that is not the case. What has changed is the medium by which we view them. Human dramas, art house films, comedies and many other genres that don’t command major box office taking are no longer being shown theatrically and are finding a home elsewhere.

This change in the way consumers access “content” has already happened within both the TV and music industries. Previously, a broad, centralised market which meant a common exposure to a variety of material has now shifted to niche platforms, channels and stations. The perennial business mantra of “greater choice” has led to audiences finding what they like but at the cost of being aware of any other kind of material. With regard to cinema such changes also have consequences. The segregation of content to specific platforms means that at the very least you’re limiting your choice to big cinematic franchises and tentpole releases. However, at worst, it leads to a form of cinematic ignorance which then contributes to a decline in the art of filmmaking. Hollywood is not known for taking risks. Until superhero movies stop making them money, that is what they’re going to continue to produce.

I count myself fortunate, as I was raised during the seventies and the three major UK TV channels used to regularly show old movies and by that I mean material from the early thirties to the late sixties. It would often take several years for major cinematic releases to get their first broadcast on analog, terrestrial television. In the eighties, video rental subsequently bridged the gap affording an opportunity to watch more recent material within the home. Hence I had a great deal of exposure to a very broad range of films. In an age where there were no video games or internet, often I would watch something with my parents out of default of anything else to do. Yet like watching “Top of the Pops”, the UKs premier music show at the time, I was presented with a wide variety of genres. As a result, I became accustomed to differing acting styles that evolved over the years as well as the pace of editing.

Two other factors secured my love of film and made it more than just a casual pastime for me. The first was joining the film club at school. I was again very fortunate to go to a senior school that focused not only on academia but the arts as well. One chemistry teacher had an abiding love of cinema and used to show fairly recent films. Afterwards there would be a discussion about the plot and the techniques used. It was a most illuminating experience. The second was joining the British Film Institute and attending screenings of classic films at the National Film Theatre on the London Southbank. It was here that I saw such giants of cinema as Ray Harryhausen and Vic Armstrong. Enjoying such events with an audience of like minded people is also a key factor and something I’ll discuss further in this post. Cinema is not a lone experience. Much of its enjoyment comes from the group experience and then discussing things afterwards.

As someone who enjoys cinema and all manner of films, I like to encourage those who are similarly disposed towards the medium to broaden their cinematic horizons. This is not driven by elitist snobbery but more of a sense of “why miss out on so much good stuff”? For example, if you like cheese why just limit yourself to cheddar? If such a philosophy seems reasonable to you and you would like to become more experimental in your viewing habits, here are a few suggestions that may help you achieve that endeavour.

Do not put arbitrary limits upon what you will or won’t watch. That’s not to say that you should throw caution to the wind. Still exercise some sense of choice but temper it. If you like contemporary horror, then why not try one from the nineties or an earlier period? Take measured steps, rather than jump into the deep end but do step outside of your usual comfort zone.

Context is king. Film reflects the prevailing social views and conventions of the time. Culture has changed greatly over the last 100 hundred years. Therefore, modern audiences will often be confronted with opinions and ideologies that are very different to what they are now. Hence it helps greatly to cultivate a sense of detachment when watching older films. You can enjoy or at least appreciate the artistry of a film such as Gone With the Wind, without endorsing its dated racial representations and social philosophies. Film in many ways are invaluable historical documents (not as in Galaxy Quest, though) and a window on the past.

Watching a film as part of a group can radically change the overall viewing experience. Charlie Chaplin viewed alone can seem very dated, repetitive and even unfunny. But watching the same material with friends or as part of a wider audience can change the dynamic. Horror and comedy produce discernable emotions and we pick up on that both consciously and subconsciously. You may well find Chaplin far more approachable in such an environment. With this in mind, join a film club. Alternatively, watch a live stream and participate in a shared experience that way. Talk and discuss both before and after watching a film (but never during).

Seek out informed people on social media. Learning about the provenance of a classic film or finding out about its troubled production history can really add to your enjoyment. It also helps to become familiar with the basics of filmmaking. If you understand the essentials of editing, framing shots, script writing, narrative arcs and styles of acting, it allows you to appreciate why some films are either venerated or reviled.

Eschew film snobbery. Cinema can be high art, mainstream entertainment and exploitative trash. It is perfectly feasible to be able to like and find merit in all of these manifestations. Also, don’t feel obliged to slavishly join the prevailing consensus of so-called “classics”. Don’t be deliberately contrary but if you don’t feel especially moved by a much loved film, then that’s fine. Just remember that the reverse is true. People are allowed to dislike the films you hold dear. Judge films on their own merit and within an appropriate context. Don’t make the mistake of comparing apples with oranges. One can admire Citizen Kane as well as enjoy the fun inherent in Treasure of the Four Crowns but to directly hold one up against the other is illogical.

If possible, find streaming platforms or TV channels that curate content that suits your needs. If you’re based in the UK then I wholeheartedly recommend Talking Pictures TV. It shows a wealth of old, obscure and even cult material. We also have the benefit of living in an age where most content can be watched in high definition. Seek out broadcasts and streams that show films in their correct aspect ratio, preferably without adverts and on screen graphics. However, don’t miss an opportunity to see something just because it’s not presented in an optimal fashion.

Finally, a love of film is like many other hobbies; inherently social. Talk about what you’ve watched and enjoyed. Write a blog, make videos on YouTube, or just chat on Twitter. Word of mouth and recommendations from friends can lead you to discover some real hidden gems (and a few turkeys). Don’t be afraid to experiment. If something doesn’t grab your attention then stop watching and try something else. Watching a film isn’t a legally binding contract in which once started, you’re compelled to continue to the end. As I said previously, why limit yourself. There are so many good films out there, from all over the world, covering every aspect of the human condition.

Cinema, Risk Aversion and Creativity

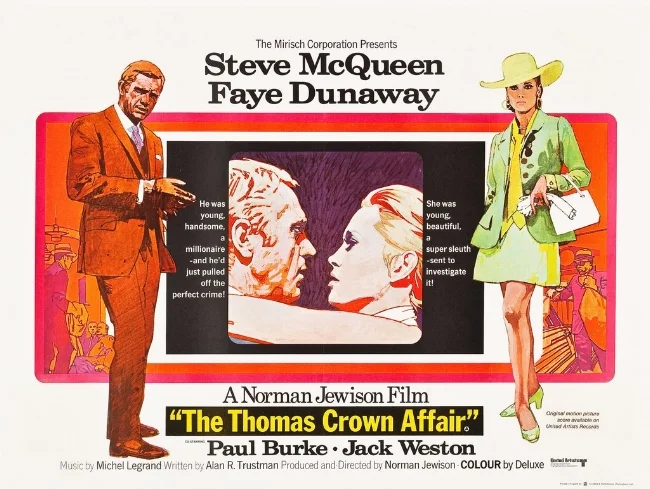

Paramount Pictures’ recent decision to forgo a worldwide theatrical release for Alex Garland’s innovative science fiction movie Annihilation and to sell it directly to Netflix, is still a matter of debate. It raises a wealth of issues from the current culture of financial risk aversion that dominates Western society, right the way through to gender politics. It certainly highlights the fact that the bottom line is now the primary motivator of any mainstream studio film production. All other considerations be they artistic, socio-political or just telling a good story are now subordinate to whether or will not a movie will make a predefined return on investment. It can therefore be cogently argued that many classic films from the sixties and seventies such as Bullitt, Deliverance and Dog Day Afternoon or would not be approved for production if they were pitched to studios in the current climate.

Paramount Pictures’ recent decision to forgo a worldwide theatrical release for Alex Garland’s innovative science fiction movie Annihilation and to sell it directly to Netflix, is still a matter of debate. It raises a wealth of issues from the current culture of financial risk aversion that dominates Western society, right the way through to gender politics. It certainly highlights the fact that the bottom line is now the primary motivator of any mainstream studio film production. All other considerations be they artistic, socio-political or just telling a good story are now subordinate to whether or will not a movie will make a predefined return on investment. It can therefore be cogently argued that many classic films from the sixties and seventies such as Bullitt, Deliverance and Dog Day Afternoon or would not be approved for production if they were pitched to studios in the current climate.

In many respects this is about morality, principles and ethics. Things that are frequently common to directors, writers and actors, especially those just beginning their careers. But such qualities can be conspicuously absent in twenty first century businesses. And their scarcity subsequently impacts upon the scope and quality of movies currently in production. It is worth considering that if current attitudes had prevailed seventy-eight years ago, then Chaplin may well have never made one of the greatest political satires ever, The Great Dictator. Something he did at considerable risk to himself. The thing is that when cinema is at its best, it is art. Art has always been an invaluable means of challenging the status quo. It can highlight new ideas, critique social and political issues or simply just bring matters to the publics attention, for their consideration. Art is therefore political and very much a question of expressing an opinion. Sadly, to Hollywood politics and “opinions” are risky. Disney’s recent parting company with director James Gunn highlights this.

Not all movies meet the nebulous criteria to be deemed as art and many more are happy just to entertain and to provide audiences with an amusing diversion. But even a mainstream production can still have a positive impact on audiences’ opinions and influence change. For example I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang shed light on a topical issue at the time of its release in 1932, and helped instigate change with regard to such penal practices. The studio and the film makers behind the movie made political enemies as a result but it still did not deter them. It is this moral component that seems to be conspicuously absent these days. Perhaps such notions of ethics and social responsibility have finally been driven out of mainstream US film making. If that is the case, then it is a tragedy for both the industry and consumers alike.

In recent decades we have scene a reversal of roles between TV and cinema. TV is now the home of cerebral, character driven narratives that explore complex and difficult themes. Commercial cinema is now about light and undemanding entertainment. Hence, we have seen the rise of the lucrative PG-13 rating, which has been tailored to satisfy the need for a degree of adult themes and violence, yet still accommodates broader audiences to ensure maximum box office returns. Yet demanding that movies conform to such a strict set of content criteria is extremely restrictive creatively. Furthermore, the growth of international markets, especially China, also impacts upon the scope and tone of movies. Striving to create a generic product that fits all international markets, usually means divesting them of local flavour and style. It can certainly impact upon content. The Red Dawn remake of 2010 sat of the shelf for two years after the collapse of MGM studios. When it was finally released in 2012, the Chinese market had grown lucrative, forcing the new owners to repurpose the film and change the main antagonist from China to North Korea. The final release is a dog’s dinner.

It would appear that this cultural reticence to engage with certain subjects, less they harm sales, is so great that even A list directors are now being shown the door. Hence, we find alternative platforms such as Netflix, providing an environment where a director can pursue a “higher risk” project more freely. Naturally independent film makers will still pursue their own agenda and will not be perturbed by commercial considerations and constraints. In the long term, the current culture of risk aversion versus creativity will result in films simply moving to the platforms and out lets that suit their needs best. However, while the current trend remains dominant, it does mean that mainstream choice will become increasingly homogenous. Yet such a policy is ultimately sowing the seeds of its own destruction. There will come a time when the market for Super Hero movies and Star Wars sequels will be saturated and once again, Hollywood will look to the independent sector to innovate and fill the gaps in the market. Movie making is after all, cyclical and governed by trends like all other leisure industries.