The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone (1990)

The Godfather Part II (1974) effectively ended the story of Michael Corleone. The man who so resolutely argued he would not become like his father ended up doing exactly that. In doing so it cost him his wife, his relationship with his children and arguably his soul. The film ends with Michael reflecting upon his past and family, all powerful but utterly alone. So in many ways, there was no major artistic or narrative requirement for a third instalment. Francis Coppola himself had no desire to return to the story. However a decade later, after a string of box office failures, he found himself in debt and in need of a financial solution. It was at this point that Paramount Pictures long standing offer to make a third Godfather movie, suddenly became a practical necessity. Coppola never intended it to be a comparable instalment to the original duology but more of a cinematic codicil. Sadly, the studio, the critics and ultimately, the viewing public never saw it that way. The rest is cinematic history and The Godfather Part III (1990) remains to this day a strongly debated film.

The Godfather Part II (1974) effectively ended the story of Michael Corleone. The man who so resolutely argued he would not become like his father ended up doing exactly that. In doing so it cost him his wife, his relationship with his children and arguably his soul. The film ends with Michael reflecting upon his past and family, all powerful but utterly alone. So in many ways, there was no major artistic or narrative requirement for a third instalment. Francis Coppola himself had no desire to return to the story. However a decade later, after a string of box office failures, he found himself in debt and in need of a financial solution. It was at this point that Paramount Pictures long standing offer to make a third Godfather movie, suddenly became a practical necessity. Coppola never intended it to be a comparable instalment to the original duology but more of a cinematic codicil. Sadly, the studio, the critics and ultimately, the viewing public never saw it that way. The rest is cinematic history and The Godfather Part III (1990) remains to this day a strongly debated film.

Numerous story ideas were conceived and abandoned while writing The Godfather Part III. Francis Coppola and co-writer Mario Puzo considered several grandiose plots before deciding that less is more and focusing on a narrative driven by Michael Corleone’s need for redemption and even forgiveness. Some critics felt that this approach contradicted the first two movies which culminated in Michael dispassionately embracing his fate. However, a man in his autumn years has much to reflect upon and therefore the film themes of redemption and trying to reinvent oneself were plausible and relevant. In fact one could argue that Coppola was trying to do as much himself. But therein was the problem. Coppola wanted a low key appendix to his previous work where the studio and public wanted another sprawling saga of criminal endeavour and a further examination of the dark heart of American culture. And so both groups fought every step of the way. They fought over the title, action set pieces, casting (as they did with the original film) and overall the scope of the story.

Upon release, many were wrong footed by the tone and direction of The Godfather Part III. It wasn’t so much that a sacred cow had been violated but that viewer expectations and the vision of the director were poles apart. The disappointment that some felt was palpable and so criticism was vocal and mainly directed at Coppola’s casting of his own daughter, who had stepped into the role out of necessity. Her performance is tonally different from the rest of the cast but is not as questionable as some would have. Certainly Al Pacino and Diane Keaton are on superb form, effortlessly picking up their respective roles and reasserting them with confidence. The standout of the film is certainly Andy Garcia who plays Vincent Mancini, the illegitimate son of Sonny Corleone. His character is straight out of King Lear and he gives a dynamic performance. The lack of Robert Duvall as Tom Hagen is a sore blow. George Hamilton plays a more contemporary corporate shark, B. J. Harrison but he lacks the emotional impact of his predecessor.

Because of the nature of the story, The Godfather Part III swaps the historical settings that were so lovingly recreated in the first two movies for the rather less enthralling world of big business circa 1979-80. There are location shots in Rome and Sicily but the change in scope does pale in comparison with the grandeur of the parts I and II, with its recreation of 1917 New York, Havana and pre-war Sicily. However, the cinematic style of Gordon Willis’ cinematography provides a sense of ongoing continuity. Willis shot both previous films although here, much of the story is swathed in shadow and darkness, reflecting the theme of spiritual doubt and conflict. These subtle changes in direction all contributed to the sense of confusion and conflict so many felt about The Godfather Part III. The best analogy I’ve seen that summarises this is that of a major recording artist, who having to two hit and and genre defining albums, then follow them up with a far more modest and specific musical foray that is far more low key in its intent.

Such has been the legacy of The Godfather Part III up until now. Coppola has recently released a revised edition of the film in which he strives to bring things back to his original vision. Retitled The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone (his preferred title) there are a range of revisions intended to make the story’s intent clear and to present it for criticism on its own merits, rather than on its pop culture baggage. Firstly, the original opening scene depicting the now vacant Corleone home on Lake Tahoe, with all it’s associated memories, has gone. The new edit starts with Michael negotiating the bailout of the Vatican bank and it emphatically states the film’s core theme; the need for redemption. Gone is the ceremony in which he receives a medal from the church for his charitable work. The film now continues with the story of how Michael is dragged kicking and screaming back into a world of crime, despite wanting to reconnect with his son and daughter. Five minutes has been removed overall and some changes are simply alternate takes or a reordering of scenes. The biggest and most subtle change is the ending. Originally, this showed Michael a broken old man, reflecting on the past and then dying in his garden chair. This time round the montage of memories are exclusively about his dead daughter and the scene then fades to black. His titular death is now figurative and not literal.

The original theatrical version of the death of Don Licio Lucchesi

I would like to reference one change that noticeably stands out in The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone. The first two movies were considered violent by the standards of the time and that violence was depicted credibly, rather than sensationally. Coppola worked with makeup effects legend Dick Smith resulting in several iconic and powerful scenes. Moe Green getting shot in the eye while having a massage, Don Fanucci getting shot in the face, Don Ciccio’s stabbing. Although the original theatrical release of The Godfather Part III in 1990 had some shootouts and bloodshed, it lacked any of the director’s signature bravura set pieces. The nearest that came to this was the death of Don Licio Lucchesi, who was stabbed in the carotid artery with his own broken pair of glasses. This was edited down to the briefest of shots in the initial release, which then focused on the bloody aftermath. In this revised edition an alternative take is used featuring major prosthetic work from Tom Burman. The scene now sports a bloody wound and a jolting arterial spurt. Compared to the violence that proceeds it this is shocking but justifiable within the film's own internal logic.

The revised version of the death of Don Licio Lucchesi

Overall this re-edit is a subtle reframing of the theatrical edition, rather than a wholesale revision. Some of the issues inherent in the first cut are still present. Too many of the new characters are not as well written compared to those that are already established. The Vatican storyline although interesting, may not be as appealing to some viewers expecting more traditional gangster tropes. Coppola recently revisited his 1984 production of The Cotton Club, which is another example of his work suffering due to studio interference. The revisions to that film, now retitled The Cotton Club Encore, have significantly altered and improved the narrative, by focusing more upon the African American cast members, who were so egregiously marginalised in the theatrical version. The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone does not achieve this degree of transformation. Instead it is content with just polishing the previous presentation by thoughtfully restructuring what was already there. Hopefully in doing so, it will lead to a more level headed reassessment of the film where it is finally judged for what it is, rather than what people wanted it to be.

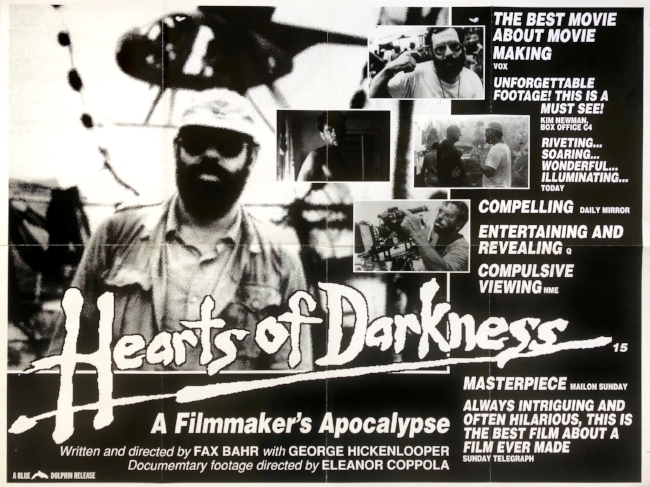

Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse (1991)

There was a time when film making was seen as an artistic endeavour and the idea of the auteur director pursuing a vision was considered a romantic and even noble undertaking. Big multi-million-dollar productions were welcomed when they filmed on location, providing work and glamour to the local population. The might of the dollar would often grease the wheels of industry, making the impossible possible. Egos were massaged, and actors were indulged and treated like minor deities. Huge sets would appear in the middle of nowhere, like Victorian follies and luxury items would be flown around the world to placate the capricious nature of the various Hollywood stars. Money would flow like water, much to the dismay of the producers, sitting back in the offices in the US or Europe. But this era has now past. Big budget movies are still made but it is now driven by corporate accounting and artistic vision is no longer a primary consideration. It is now a rather soulless business process. Hence a movie such as Apocalypse Now would never be made today in the same manner that it was back in 1976 when the production started.

There was a time when film making was seen as an artistic endeavour and the idea of the auteur director pursuing a vision was considered a romantic and even noble undertaking. Big multi-million-dollar productions were welcomed when they filmed on location, providing work and glamour to the local population. The might of the dollar would often grease the wheels of industry, making the impossible possible. Egos were massaged, and actors were indulged and treated like minor deities. Huge sets would appear in the middle of nowhere, like Victorian follies and luxury items would be flown around the world to placate the capricious nature of the various Hollywood stars. Money would flow like water, much to the dismay of the producers, sitting back in the offices in the US or Europe. But this era has now past. Big budget movies are still made but it is now driven by corporate accounting and artistic vision is no longer a primary consideration. It is now a rather soulless business process. Hence a movie such as Apocalypse Now would never be made today in the same manner that it was back in 1976 when the production started.

Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse is one of the best “movies about the making of a movie” ever made. It provides not only a window into them making of one of the most important movies of the seventies but also offers a snapshot of a kind of film making that simply doesn’t exist anymore. After several years of pre-production writer/director Francis Ford Coppola arrived in the Philippines in 1976 and quickly found himself drowning in the logistical, political and human aspects of this mammoth project. He asked his wife Eleannor to document the process which she dutifully did, filming events on and off set and recording conversations with her husband as the production started to spiral out of control. Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse shows all this and more, in broad chronological order over the period of the extended location shoot. As for all the stories surrounding the “troubled” production of Apocalypse Now, they’re all broadly true. To catalogue them is somewhat redundant as it fails to adequately convey they’re true significance or magnitude. But to watch them happening first hand is utterly astounding.

Two of aspects of the production of Apocalypse Now that really stand out are the complex logistical requirements and human management. This was a big budget movie made in the days before computer effects. Therefore, the action scenes where shot on location and for real. A shot requiring a napalm strike in the treeline would subsequently feature a low fly-by by a jet plane and then tons of gasoline exploded by the effects crew, all flawlessly timed. Another scene featuring the crew exploring the jungle and encountering a tiger again would be undertaken with a live tiger and a handler. If the script required an ageing temple set in the jungle, then one would simply be built by local labour. Despite a typhoon destroying multiple sets early on in the production, the moment the weather nominally abated, then the crew were out filming, incorporating the extreme conditions into the narrative. And then there was the entire issue of the cast and their “personal journeys”. To reflect the reality of a soldier’s life in Vietnam, drugs were freely used among the production crew and actors. And presiding over this chaos was Coppola himself. Eleannor Coppola wrote of his experience “The film Francis is making is a metaphor for a journey into self. He has made that journey and is still making it. It's scary to watch someone you love go into the centre of himself and confront his fears, fear of failure, fear of death, fear of going insane. You have to fail a little, die a little, go insane a little, to come out the other side. The process is not over for Francis”.

But perhaps the most significant obstacle to challenge the production was its very own star, Marlon Brando. The seventies were a decade in which the “Hollywood Star” was still a revered, cultural icon. I cannot think of a circumstance nowadays in which a lead artist would be allowed to inconvenience an entire film production so much, while being indulged and cossetted. Brando’s intransigence and hubris were monumental, and he arrived on set late into the production with little or no preparation for the role. His continual questioning and debating the script verged upon gas lighting and his utter indifference to the rest of the cast was a major impediment. It is much to Coppola’s credit that he allowed the actor to eventually just extemporise around certain plot elements and from the hours of footage shot, collate such a powerful performance. When the production finally ended after sixteen months, it took a further year for the director to assemble a workable print of the movie. Half of the original script, written by John Milius, was re-written by Coppola himself and post production required the return of many cast members to re-record new lines and the framing narration.

If one has no knowledge of film history, it would be reasonable to assume after watching the documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse, that the resultant film, Apocalypse Now, was an absolute disaster both critically and financially. However, that was not the case and the movie is now hailed as a “haunting, hallucinatory Vietnam war epic” and “cinema at its most audacious and visionary”. Certainly, the entire production and associated apocrypha surrounding the film can be seen as a metaphor to the entire Vietnam War in itself. As for Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse it is an invaluable exploration of film making process of the times. It not only catalogues but appears testifies to the notion that creating art is a painful and extremely difficult process. Yet the key to success is to stay true to your artistic vision, whatever the cost. Whether you agree with such concepts is up to you to decide. Is Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse showing us the struggles of an auteur director or simply recording the runaway indulgences of an ego maniac? Either way it is an incredible and utterly fascinating documentary to watch.