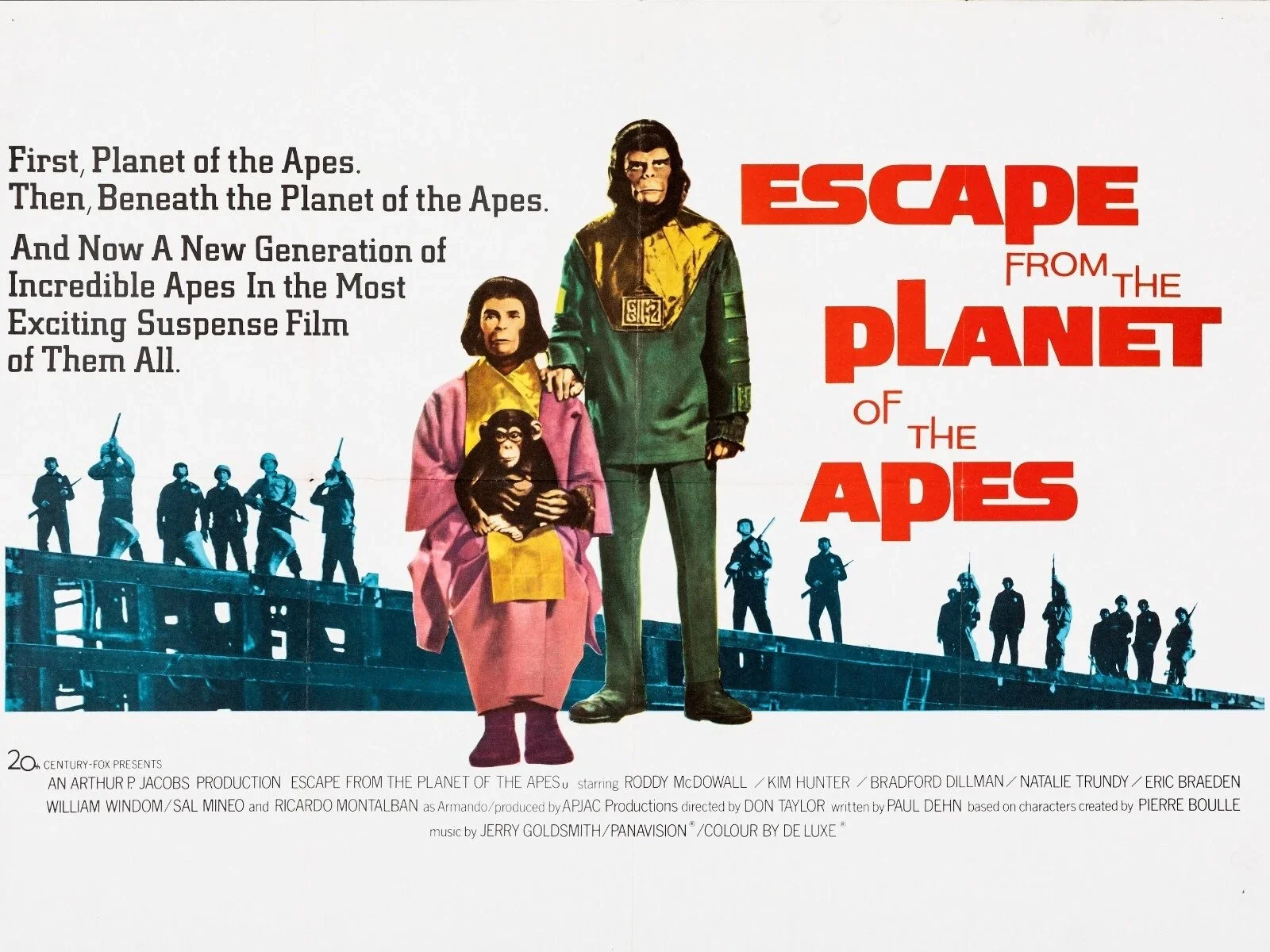

Classic Movie Themes: Escape from the Planet of the Apes

The Planet of the Apes movie franchise took a radical change of course with its third entry in the series. The first two films were set in the future and benefited from high production values to help realise a post apocalyptic earth. However, due to a substantial reduction of budget, Escape from the Planet of the Apes uses a time travel plot device to bring the ape protagonists to present day Los Angeles (1971 in this case). The result is a film with a much smaller narrative scope. However, although it lacks the science fiction spectacle of its predecessors, it features an interesting satirical exploration of celebrity culture and ponders what it is like to be deemed an enemy of the state. As ever, Roddy McDowell and Kim Hunter provide exceptional lead performances as the Chimpanzees Cornelius and Zira. Escape from the Planet of the Apes also captures the pop culture vibe of seventies America.

The Planet of the Apes movie franchise took a radical change of course with its third entry in the series. The first two films were set in the future and benefited from high production values to help realise a post apocalyptic earth. However, due to a substantial reduction of budget, Escape from the Planet of the Apes uses a time travel plot device to bring the ape protagonists to present day Los Angeles (1971 in this case). The result is a film with a much smaller narrative scope. However, although it lacks the science fiction spectacle of its predecessors, it features an interesting satirical exploration of celebrity culture and ponders what it is like to be deemed an enemy of the state. As ever, Roddy McDowell and Kim Hunter provide exceptional lead performances as the Chimpanzees Cornelius and Zira. Escape from the Planet of the Apes also captures the pop culture vibe of seventies America.

The soundtrack for Escape from the Planet of the Apes, marked the return of composer Jerry Goldsmith, whose score for Planet of the Ape had been nominated for an Oscar. On this occasion Goldsmith shifts from the stark, avant-garde style of the first film, to a lighter, more upbeat seventies sound, reflecting the film’s comedic and romantic elements. However, Goldsmith still maintains his signature use of unconventional percussion, brass, and innovative orchestral techniques. The result is a unique, fun and charming score which despite being very much of the time, does a great deal to bolster the unfolding drama. The title theme stands out with its unusual time signature and rhythmic bassline, played by the legendary session musician Carol Kaye. Goldsmith also uses both sitar and steel drums adding to the quirky character of the piece.

Despite the lighter tone of Jerry Goldsmith’s soundtrack, Escape from the Planet of the Apes is a very bleak film with respect to its ending, which features infanticide. Musically, unlike the oppressive dread of the Planet of the Ape, the score for this film embraces the musical informality of the early seventies. The cue “Shopping Spree” captures the romantic interactions between Cornelius and Zira, incorporating charming piano melodies. While tracks such as “The Hunt” offer moments of suspense and are written in a more traditional idiom. However, the main title theme for the film remains the stand out track and is presented here for your enjoyment. It remains a prime example of the inherent versatility of composer Jerry Goldsmith who on this occasion goes for a more pop infused approach to his writing. The result is a charismatic soundtrack that captures the essence of the film and the mood of the time.

Classic TV Themes: The Prisoner

Ronald Erle Grainer (11 August 1922 – 21 February 1981) was a prolific Australian composer who is best remembered for his work in the United Kingdom during the sixties and seventies. He wrote numerous notable scores and theme music for several iconic television shows such as Doctor Who, Steptoe and Son and Tales of the Unexpected. He also composed the soundtrack for several major motion pictures such as Some People (1962), The Assassination Bureau (1969) and The Omega Man (1971). Grainer relocated to London from Australia in 1952 but it was not until 1960 that he gained critical success after writing the music for the popular TV show Maigret. He subsequently received an Ivor Novello award for “Outstanding Composition for Film, TV or Radio”.

Ronald Erle Grainer (11 August 1922 – 21 February 1981) was a prolific Australian composer who is best remembered for his work in the United Kingdom during the sixties and seventies. He wrote numerous notable scores and theme music for several iconic television shows such as Doctor Who, Steptoe and Son and Tales of the Unexpected. He also composed the soundtrack for several major motion pictures such as Some People (1962), The Assassination Bureau (1969) and The Omega Man (1971). Grainer relocated to London from Australia in 1952 but it was not until 1960 that he gained critical success after writing the music for the popular TV show Maigret. He subsequently received an Ivor Novello award for “Outstanding Composition for Film, TV or Radio”.

By the mid-sixties Grainer was in demand and hence a logical choice to write the theme for a show such as The Prisoner. However, it was a competitive process and Grainer's theme was chosen after two other composers, Robert Farnon and Wilfred Josephs, had their material rejected by series executive producer and star, Patrick McGoohan. Farnon's theme was declined due to its similarity with the theme from The Big Country (1958) by Jerome Moross. However, Josephs' discordant and enigmatic theme was used in early edits of two episodes of The Prisoner before being replaced by Grainer’s material which was then used in all subsequent episodes. It should be noted that Grainer declined to score the incidental music for the entire series of 17 episodes, which was handled by Albert Elms.

Ron Grainer’s theme for The Prisoner is as iconic as the show mainly because it is such an integral part of the opening credits. These are a microcosm of themes and ideas that the show explores. Furthermore, the opening credits serve as visual summation of the plot of The Prisoner, with Patrick McGoohan resigning from his job as an agent for the UK security services, only to be gassed, kidnapped, and taken to a remote village where he is interrogated for “information”. Why did he resign? The brass, bass and timpani set the tone with a bombastic motif that reflects McGoohan’s volatile character. The music also reflects what is happening on screen with the drumbeats syncopated with McGoohan as he angrily walks down the concrete corridor into his superior’s office. This is a powerful piece reflecting the style of the time, with its bold brass and cool, electric guitar backing. It really sets the tone of the show.

Listening to Music

The following is about a cultural change. That is not to say that it’s a value judgement or one of those posts you so frequently read by bloggers of a certain age, that essentially boil down to “things were better in my day”. It is merely an observation and like all observations it is not 100% universal. There will always be exceptions to the rule. I am simply painting with broad strokes a general truism for your consideration. My point being that people listen, experience and enjoy music differently these days compared to how they did three to four decades ago. I’m not talking about the science of hearing or anything complex like that. I am merely highlighting the change in the way we choose to experience music and how that has an impact upon its creation and presentation. So like Anne Elk, presenting her theory on the Brontosaurus, here is the axiom at the heart of this post.

The following is about a cultural change. That is not to say that it’s a value judgement or one of those posts you so frequently read by bloggers of a certain age, that essentially boil down to “things were better in my day”. It is merely an observation and like all observations it is not 100% universal. There will always be exceptions to the rule. I am simply painting with broad strokes a general truism for your consideration. My point being that people listen, experience and enjoy music differently these days compared to how they did three to four decades ago. I’m not talking about the science of hearing or anything complex like that. I am merely highlighting the change in the way we choose to experience music and how that has an impact upon its creation and presentation. So like Anne Elk, presenting her theory on the Brontosaurus, here is the axiom at the heart of this post.

Most people no longer listen to an album by a band or artist, in its designated order. Assuming that they listen to an album in its entirety at all. Most people curate their own playlists nowadays, drawing from multiple sources. They cherry pick the music they like and ignore those tracks they deem just average or worse. Hence the idea of listening to an album from start to finish is to a degree, obsolete. Perhaps the idea of the album itself is equally anachronistic. All of which pretty much negates the existence of the concept album. These changes in the way we listen to (or should I say consume) music has also had an impact upon radio stations and especially upon the relevance of the traditional notion of the DJ. All of which was brought home to me today, when I decided to listen to the 1976 synth-based ambient album Oxygène by Jean Michel Jarre. Something I last listened to about forty years ago.

Originally created as a concept album (“an album whose tracks hold a larger purpose or meaning collectively than they do individually” according to Wikipedia), Oxygène was intended to be listened to continuously for 40 minutes, playing the tracks in chronological order. Naturally, the nature of vinyl recordings and playback greatly governed this habit. The idea was to not only enjoy each specific piece of music but to see them as an interconnected whole that conveyed a wider message. The concept album was a means of bridging the gap between popular music genres and more formal musical compositions, by applying concepts used by the classics. This could be a common or recurring motif, an operatic structure or just a semblance of a narrative structure in the various lyrics. The definition of the concept album is purposely vague, yet you’ll know one if you hear one.

Based upon my own experience, I started my love affair with popular music in the early eighties and on into the late nineties. Like so many others, my teenage years were defined by a need to find some sort of identity and that was often linked to the music you liked and its associated culture. Fortunately, although there were specific genres that I liked, I was happy to explore others and have maintained this philosophy all my life. However, back then in the eighties, there were less distractions and demands upon our leisure time.Therefore, when I listened to music, I was not doing anything else at the time. I was focused upon listening and digesting what I heard. It required a degree of application that rewarded you in a different way to casual listening.

It is also worth noting that some albums were created to be listened to in a specific way. There is a clear arc to the track listing on The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and Pink Floyd’s The Wall. Naturally, the listener is not bound by such notions and is free to ignore such things if they wish. But it does raise the question, that by listening to the songs out of order and context, do you diminish the musician's artistic vision? However, if you have grown up in a world where such habits as just listening to music and doing so in a linear fashion aren’t the norm, it probably seems all rather alien. Amazon Music has embraced the random playlist concept to such a degree, it won’t play an album in order, even if you own it. For many people, the old fashioned notion of an album has been replaced by exchanging or downloading carefully curated playlists. It could be argued that such things are conceptual in principle themselves.

We all have our own unique relationship with music, especially that we enjoy in our most formative years. For some, it is an integral aspect of their life, identity and the way in which they process the world. For others, to paraphrase Karl Pilkington “music is just something to sing along to” while you do something else. It is disposable and no more than the sum of its parts. Whatever your perspective, we all “do” music differently these days. The fact that the very term “listening” seems to have been replaced with “consume” implies a radical change in perception. As does the way so many of us experience the music we like. In our own, niche online communities, oblivious and indifferent to anything that is not within the confines of our taste. Whether any of these points mean anything or not, you’ll have to decide for yourself. Maybe we’ve become liberated, as opposed to having lost something. Perhaps nothing has changed at all. Regardless, I still enjoyed spending 40 minutes listening to Oxygène today.

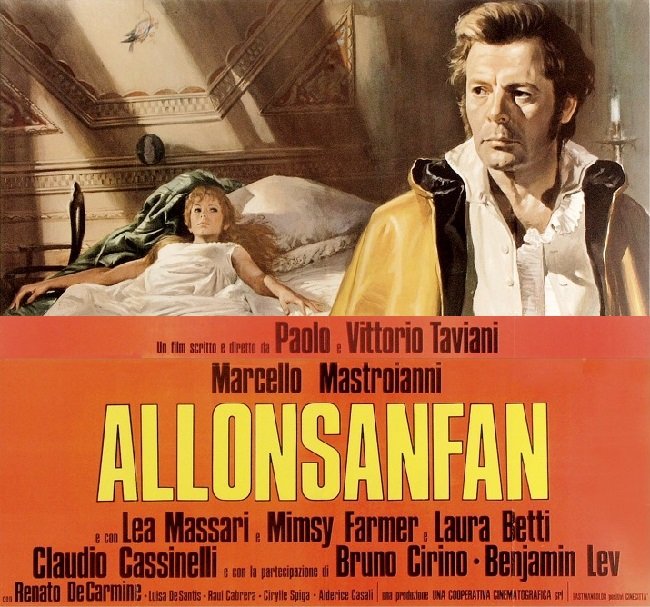

Classic Movie Themes: Allonsanfàn

Allonsanfàn (1974) is an Italian historical drama film written and directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani. The title of the film derives from the first words of the French Revolutionary anthem La Marseillaise (Allons enfants, IE “Arise, children”). It is also the name of a character in the story. Set against the backdrop of the Italian Unification in early 19th-century Italy, Marcello Mastroianni stars as an ageing revolutionary, Fulvio Imbriani, who becomes disillusioned after the Restoration and endeavours to betray his companions, who are organising an insurrection in Southern Italy. Allonsanfàn is a complex film that is not immediately accessible to those unfamiliar with the intricacies of Italian political history nor the arthouse style of the Taviani brothers. However, it is visually arresting and features a rousing score by Ennio Morricone.

Allonsanfàn (1974) is an Italian historical drama film written and directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani. The title of the film derives from the first words of the French Revolutionary anthem La Marseillaise (Allons enfants, IE “Arise, children”). It is also the name of a character in the story. Set against the backdrop of the Italian Unification in early 19th-century Italy, Marcello Mastroianni stars as an ageing revolutionary, Fulvio Imbriani, who becomes disillusioned after the Restoration and endeavours to betray his companions, who are organising an insurrection in Southern Italy. Allonsanfàn is a complex film that is not immediately accessible to those unfamiliar with the intricacies of Italian political history nor the arthouse style of the Taviani brothers. However, it is visually arresting and features a rousing score by Ennio Morricone.

The Tavianis brothers’ previous composer Giovanni Fusco introduced Morricone to the directors, who initially didn't want to use any original music for the film. As Morricone was not disposed towards arranging anyone else's work he insisted upon writing his own material or he would leave the production. Upon hearing the motif he created for the climatic “dance” scene, the Tavianis brothers immediately set aside their previous objections and gave Morricone free reign. Hence, Morricone’s deliciously inventive score is part of the fabric of the film, providing a pulse to the story. This is most noticeable in the scene in which Fulvio’s sister Esther (Laura Betti) turns a half-remembered revolutionary song into a full-blown song-and-dance number and when Fulvio himself borrows a violin in a restaurant to impress his son. Allonsanfàn may not be to everyone’s taste but Morricone’s score is very accessible.

Perhaps the most standout track from the film’s score is “Rabbia e tarantella” (Revolution and Tarantella). A Tarantella is a form of Italian folk dance characterised by a fast upbeat tempo. Morricone has crafted a remarkably rhythmic piece featuring aggressive piano and low-end brass against a backdrop of a stabbing string melody. All of which is driven and underpinned by the timpani drum which robustly punctuates the track. It is certainly not your typical tarantellas of Italian folk but it is a catchy piece that highlights the innate understanding of music that Ennio Morricone possessed and how he could bring this talent to bear on any cinematic scene. “Rabbia e tarantella” was subsequently used during the closing credits of Quentin Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds (2009). Due to its inherent quality it survives being transplanted into a film with a completely different context.

Classic Movie Themes: Star Trek First Contact

Jerry Goldsmith’s contribution to Star Trek is immense. Yet simply listing the films and TV episodes he wrote music for does not adequately encapsulate the significance of his contribution to the franchise. His majestic, thoughtful and uplifting musical scores provide an emotional foundation that reflects the core ethos of Star Trek. They also create an invaluable sense of continuity that spans multiple shows and movies. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is his iconic title music for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) that was subsequently adopted as the theme tune for Star Trek: The Next Generation. His work was held in such high regard, when Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989) ran into production issues, it was thought that a Jerry Goldsmith soundtrack may well elevate the film. Sadly it didn’t but his work on that instalment was outstanding and among his best.

Jerry Goldsmith’s contribution to Star Trek is immense. Yet simply listing the films and TV episodes he wrote music for does not adequately encapsulate the significance of his contribution to the franchise. His majestic, thoughtful and uplifting musical scores provide an emotional foundation that reflects the core ethos of Star Trek. They also create an invaluable sense of continuity that spans multiple shows and movies. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is his iconic title music for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) that was subsequently adopted as the theme tune for Star Trek: The Next Generation. His work was held in such high regard, when Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989) ran into production issues, it was thought that a Jerry Goldsmith soundtrack may well elevate the film. Sadly it didn’t but his work on that instalment was outstanding and among his best.

Jerry Goldsmith returned to the franchise in 1995, writing the dignified and portentous Star Trek: Voyager theme. Again this succinctly showed the importance the producer’s of the franchise attached to his work. Then in 1996 Goldsmith wrote the score for Star Trek: First Contact. Again his music demonstrates his ability to imbue the film’s narrative themes and visual effects with an appropriate sense of awe and majesty. Although contemporary in his outlook, with an inherent ability to stay current, Goldsmith had studied with some of the finest composers from the golden age of Hollywood. Hence, there are a few cues from First Contact where the influence of the great Miklós Rózsa are quite apparent and beautifully realised. Fans will argue that his score for Star Trek: The Motion Picture is his greatest work in relation to the franchise but I think that the soundtrack for Star Trek: First Contact has more emotional content.

The track “First Contact” which comes at the climax of the film is in many ways the highlight of the entire score. Goldsmith uses English and French horns as Picard and Data reflect upon the nature of temptation after defeating the Borg Queen. When the alien vessel lands and its crew disembarks to make first contact, the melody takes on a profoundly ethereal and even religious quality, especially when the church organ reiterates the theme. This reaches a triumphant peak when it is revealed that the first visitors to Earth are Vulcan. The cue then takes a melancholy turn as Picard and Lily bid a touching farewell. “First Contact” is a sublime six minutes and four seconds which demonstrates why Jerry Goldsmith was such a superb and varied composer. It not only highlights his legacy to Star Trek but also his status as one of the best film composers of his generation.

Classic Movie Themes: Halloween

Halloween (1978) is both a genre and cinematic milestone. It made stars of Jamie Lee Curtis and director John Carpenter as well as kickstarting the slasher genre that dominated the box office for the next 15 years. Unlike many of the inferior imitations that followed in its wake, Halloween is not a gorefest but a far more suspenseful and unsettling film. It’s shocks and sinister atmosphere are the result of sumptuous panavision cinematography by Dean Cundey and inventive editing by Tommy Wallace and Charles Bornstein. Another invaluable asset to the film’s effectiveness is John Carpenter minimalistic synth and piano score which perfectly embellishes the film with an air of menace. After 33 years and various re-arrangements in subsequent sequels, the original Halloween Theme is still as effective today as it was when the film was first released.

Halloween (1978) is both a genre and cinematic milestone. It made stars of Jamie Lee Curtis and director John Carpenter as well as kickstarting the slasher genre that dominated the box office for the next 15 years. Unlike many of the inferior imitations that followed in its wake, Halloween is not a gorefest but a far more suspenseful and unsettling film. It’s shocks and sinister atmosphere are the result of sumptuous panavision cinematography by Dean Cundey and inventive editing by Tommy Wallace and Charles Bornstein. Another invaluable asset to the film’s effectiveness is John Carpenter minimalistic synth and piano score which perfectly embellishes the film with an air of menace. After 33 years and various re-arrangements in subsequent sequels, the original Halloween Theme is still as effective today as it was when the film was first released.

John Carpenter wanted a unique sound for Halloween despite the production’s modest budget. When composing the main theme he used the uncommon 5/4 time beat for a bongo drum and transferred that to piano, which resulted in the iconic melody. This uncommon sound works extremely well, clearly establishing a mood and tone that suits the film. Yet it also holds up well as a standalone piece of music. When used in the film, it is a practical audio cue to alert the audience to the presence of The Shape and potential onscreen danger. Yet the piece does not diminish in power, despite its repetition.The staccato piano rhythm with additional synthesizer chords combine to produce an evocative and infinitely flexible cue. It creates a palpable atmosphere for the film and its antagonist, yet it isn’t weighed down by excessive musical complexity.

30 years later and Halloween (2018) has proved to be a very interesting belated sequel. It features a new score by Carpenter, alongside his son, Cody Carpenter and godson Daniel Davies. The soundtrack revises the main theme and classic elements from the original as well as adding several new tracks. There is a broader use of contemporary synthesizers this time, as well as some interesting experimentation with guitar sounds. They add a real edge to a score which proves to be anything but an exercise in nostalgia. There is one cue that encapsulates the best elements of both the old and the new. The Shape Hunts Allyson. Featuring tremulous keyboards and punctuated witty grinding guitars and synths it captures an onscreen chase superbly. A variation of this cue was subsequently used at the climax of Halloween Kills (2021) and again is superbly effective in its powerful simplicity.

Yet More Cult Movie Soundtracks

Tenebrae (1982) is probably Dario Argento’s most accessible “giallo” for mainstream audiences. Although violent, it is not as narratively complex as Deep Red (1975) or as bat shit crazy as Phenomena (1985). The story centres on popular American novelist Peter Neal (Anthony Fanciosa) who is in Rome to promote his latest book. Events take a turn for the worst when a series of murders appear to have been inspired by his work. The plot twists and turns, the director explores themes such as dualism along with sexual aberration and blood is copiously spattered across the white walled interiors of modernist buildings. It is slick, disturbing and has a pounding synth and rock score by former Goblin members, Claudio Simonetti, Fabio Pignatelli, and Massimo Morante.

Tenebrae (1982) is probably Dario Argento’s most accessible “giallo” for mainstream audiences. Although violent, it is not as narratively complex as Deep Red (1975) or as bat shit crazy as Phenomena (1985). The story centres on popular American novelist Peter Neal (Anthony Fanciosa) who is in Rome to promote his latest book. Events take a turn for the worst when a series of murders appear to have been inspired by his work. The plot twists and turns, the director explores themes such as dualism along with sexual aberration and blood is copiously spattered across the white walled interiors of modernist buildings. It is slick, disturbing and has a pounding synth and rock score by former Goblin members, Claudio Simonetti, Fabio Pignatelli, and Massimo Morante.

One Million Years B.C. (1966) is a delightful collaboration between Hammer Studios and stop motion animation legend Ray Harryhausen. It is the tale of how caveman Tumak (John Richardson) is banished from his native Rock tribe and after a long journey encounters the Shell tribe who live on the shores of the sea. It’s historically inaccurate, with dinosaurs, faux prehistoric languages and Raquel Welch in a fur bikini. It is also great fun and features a superbly percussive and quasi-biblical themed score by Italian composer Mario Nascimbene. Nascimbene was an innovator and often incorporated non-orchestral instruments and random noises, such as objects being banged together or clockwork mechanisms, into his music to underpin the stories it was telling. There is a portentous quality to his main opening theme as the earth is created and primitive man emerges.

Get Carter (1971) is a classic, iconic British gangster film featuring a smoldering performance by Michae Caine. The musical score was composed and performed by Roy Budd and the other members of his jazz trio, Jeff Clyne (double bass) and Chris Karan (percussion). The musicians recorded the soundtrack live, direct to picture, playing along with the film. Budd did not use overdubs, simultaneously playing a real harpsichord, a Wurlitzer electric piano and a grand piano. The opening theme tune, which plays out as Caine travels to Newcastle by train, is extremely evocative and enigmatic with its catchy baseline, pumping tabla and echoing keyboards. The music is innovative and a radical change from the established genre formula of the previous decade which often featured a full orchestral score.

Witchfinder General (1968) is an bleak and harrowing exploration of man’s inhumanity to man, presented in a very dispassionate fashion. Matthew Hopkins (Vincent Price) is an opportunistic “witch-hunter”, who plays upon the superstitions of local villagers in remote East Anglia and takes advantage of the lawless times, brought about by the English Civil War. Price’s performance is extremely menacing and his usual camp demeanour is conspicuously absent. Director Michael Reeves paints a stark picture of the treatment of women in the 17th century. Yet despite the beatings, torture and rape, composer Paul Ferris crafts a charming and melancholic soundtrack. There is a gentle love theme that has subsequently been used in the low budget Vietnam War film How Sleep the Brave (1981) and even featured an advert for Vaseline Intensive Care hand lotion in the late seventies.

Journey to the Far Side of the Sun AKA Doppelgänger (1969) is the only live action feature film that Thunderbirds creator, Gerry Anderson, produced. It is an intriguing, cerebral science fiction film in which a new planet is discovered in an identical orbit to that of earth but on the exact opposite side of the sun. A joint manned mission is hastily arranged by EUROSEC and NASA to send astronauts Colonel Glenn Ross (Roy Thinnes) and Dr John Kane (Ian Hendry) to investigate. Upon arrival the pair crash on the new planet in a remote and barren region. Ross subsequently awakes to find himself back on earth in a EUROSEC hospital. Exactly what happened and how is he back home? Journey to the Far Side of the Sun is like an expanded episode of the Twilight Zone and boasts great production design by Century 21 Studios under the direction of special effects genius Derek Meddings. The miniature work is outstanding. There is also a rousing score by longtime Anderson collaborator Barry Gray. Gray always expressed what was happening on screen quite clearly in his music, scoring in a very narrative fashion. The highlight of the film is a pre-credit sequence where scientist and spy Dr Hassler (Herbert Lom) removes a camera hidden in his glass eye and develops photographs of secret files. Gray’s flamboyant score featuring an Ondes Martenot works perfectly with the onscreen gadgetry and red light illumination of the dark room.

For further thoughts on cult movie music, please see previous posts Cult Movie Soundtracks and More Cult Movie Soundtracks.

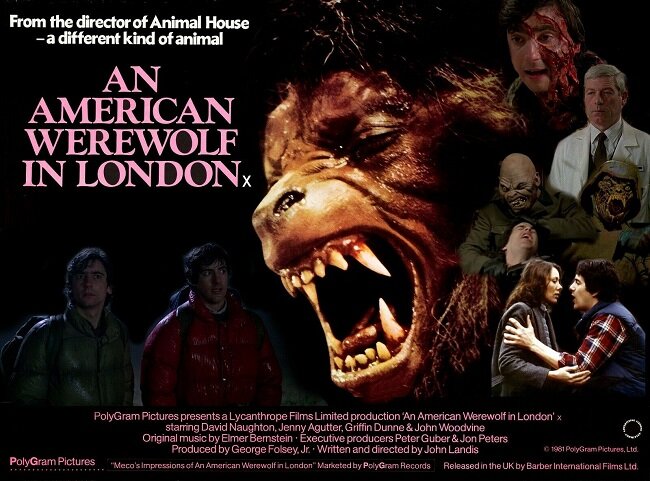

Classic Movie Themes: An American Werewolf in London

An American Werewolf in London is a genre milestone and one of the few horror films that successfully manages to balance humour and suspense without mitigating the overall tone of the story. 40 years on from its theatrical release it still holds up well with its bitter sweet love story, tragic themes and ground breaking transformation effects by Rick Baker. Director John Landis never really bettered this concise and effective genre outing. It hits the mark in virtually every part of the production. However, there is one aspect of the film that does suffer as a result of the director’s personal choices. Whether it is to the detriment of the overall film is debatable. The point in question is the film’s soundtrack and the director’s focus upon the song Blue Moon by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart.

An American Werewolf in London is a genre milestone and one of the few horror films that successfully manages to balance humour and suspense without mitigating the overall tone of the story. 40 years on from its theatrical release it still holds up well with its bitter sweet love story, tragic themes and ground breaking transformation effects by Rick Baker. Director John Landis never really bettered this concise and effective genre outing. It hits the mark in virtually every part of the production. However, there is one aspect of the film that does suffer as a result of the director’s personal choices. Whether it is to the detriment of the overall film is debatable. The point in question is the film’s soundtrack and the director’s focus upon the song Blue Moon by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart.

Hollywood veteran, Elmer Bernstein, was commissioned by Landis to write the score for An American Werewolf in London. But Landis had already decided to use a selection of songs to play during key scenes. All of which referenced the moon in some fashion, thus ironically highlighting the significance of the lunar cycle in lycanthropy. Hence the film starts with Blue Moon by Bobby Vinton playing over the opening credits. Moondance by Van Morrison is used during a love. Bad Moon Rising by Creedence Clearwater Revival accompanies a scene where the lead actor David Naughton anxiously paces round Nurse Price’s flat. Then perhaps the most notable use of a song is during the iconic werewolf transformation scene, which features Blue Moon by Sam Cooke. Finally, the end credits roll to a doo-wop version of Blue Moon by The Marcels.

The use of these songs is appropriate and more to the point works within the context of the film. I certainly understand why John Landis chose to juxtapose the shocking imagery of the werewolf transformation sequence with the sweat and wholesome tones of Sam Cooke. However, it does raise the question why employ such a canny and talented composer as Elmer Bernstein if you’re not really going to use their work. Because Bernstein did indeed compose a cue specifically for the werewolf scene, despite being told by Landis that it wouldn’t be required. He apparently produced a lot more material for the film that wasn’t used but did so as a safety net in case Landis could not secure the licenses for the songs he intended to use. You can find a detailed account of the story behind this decision over at Hollywood and All That, which makes for interesting reading if you’re a movie trivia aficionado.

There has never been a comprehensive or in fact any kind of release of Elmer Bernstein’s score for An American Werewolf in London. Soundtrack albums associated with the film tend to focus on the songs. There is a disco album by Meco called Impressions of An American Werewolf in London, which is best not talked about. However, one of the unused cues for the film surfaced in 2005. Composer and arranger Nic Raine specialises in re-recording classic film soundtracks in conjunction with the Prague Philharmonic. The Essential Elmer Bernstein Film Music Collection features a track called “Metamorphosis”. It is a five minute piece with two distinct phases. It has subsequently been determined that part of this is indeed the cue that Bernstein wrote for the werewolf transformation. Furthermore, attentive listeners have determined that elements of this track were used in Michael Jackson’s Thriller, which was also directed by John Landis and credits Elmer Bernstein for scary music.

At present, there are only bootleg scores for An American Werewolf in London or YouTube videos featuring music extracted directly from DVD or Blu-ray releases of the film. One such track circulating under the title “An American Werewolf in London suite”, features just under 4 minutes of material from Bernstein’s soundtrack. I have included it here because, despite its brevity, it includes the beautiful central motif played on piano.

As a bonus, we also have Nic Raine’s re-recording of the lost “Metamorphosis” cue. Perhaps one day a comprehensive reconstruction of the entire score will be undertaken. Until then enjoy these two tracks.

Classic TV Themes: Star Trek

Before we start, no I am not writing about Alexander Courage’s classic main theme for the original Star Trek show. I can add nothing further to that particular discussion and it remains iconic and inspiring, even when distilled down to just the initial fanfare. In this post I want to draw your attention to another piece of music from Star Trek that has permeated its way into popular culture. A cue that when heard, if the listener is familiar with its provenance, will instantly conjure up images of flying drop kicks, ear claps and judo chops. A piece of music that can be added to pretty much any video footage and instantly make it more heroic. Yes, I am talking about what has become generically known as Star Trek “fight music”. Or more specifically, the "The Ancient Battle/2nd Kroykah" cue from Amok Time (S02E01) composed by Gerald Fried. The scene during the koon-ut-kal-if-fee ritual in which Spock fights Kirk on the planet Vulcan for complicated “reasons”.

Before we start, no I am not writing about Alexander Courage’s classic main theme for the original Star Trek show. I can add nothing further to that particular discussion and it remains iconic and inspiring, even when distilled down to just the initial fanfare. In this post I want to draw your attention to another piece of music from Star Trek that has permeated its way into popular culture. A cue that when heard, if the listener is familiar with its provenance, will instantly conjure up images of flying drop kicks, ear claps and judo chops. A piece of music that can be added to pretty much any video footage and instantly make it more heroic. Yes, I am talking about what has become generically known as Star Trek “fight music”. Or more specifically, the "The Ancient Battle/2nd Kroykah" cue from Amok Time (S02E01) composed by Gerald Fried. The scene during the koon-ut-kal-if-fee ritual in which Spock fights Kirk on the planet Vulcan for complicated “reasons”.

Veteran composer Gerald Fried had written scores for Stanley Kubrick (The Killing and Paths of Glory) and had an established reputation for providing quality material for TV, having notably provided incidental music for numerous episodes of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Fried wrote the music scores for five episodes of the first season of Star Trek. Over the years the "The Ancient Battle/2nd Kroykah" cue has gained a curious cult following. This may be because the music was re-used in many more episodes throughout the second season and became among the most memorable pieces of the entire show. It featured in the Jim Carrey film The Cable Guy and was further referenced again by Michael Giacchino in Star Trek Into Darkness in a fight between Spock and Khan Noonien Singh. It is also used in the Coliseum mission in Star Trek Online.

So here for your edification and enjoyment is the complete "The Ancient Battle/2nd Kroykah" cue by Gerald Fried. It is a very flamboyant piece of music with a very sixties idiom and arrangement (dig the Bass line). For those with a liking for memes, even when played over the most mundane and arbitrary video footage, it immediately elevates the status of that material. Hence you will find YouTube videos of cats fighting and people struggling to put out their bins, with this track playing in accompaniment. I personally like the cue for what it is. It always elicits fond memories of Star Trek TOS which was a staple of my youth. It also reminds me that music was a far more prominent aspect of TV shows back in the sixties and seventies and that a lot more time and effort was spent on writing a score. So grab a Lirpa, rip your T-Shirt at the shoulder and do some forward rolls. It’s time to fight!

Classical Music in Movies

Classical music has often been used to great effect in cinema since the advent of sound. It has certain advantages over bespoke compositions, in that it can imbue a scene with a sense of gravitas and emotionally connect with viewers who may already be familiar with the piece being played. Legendary director Stanley Kubrick famously rejected Alex North’s score for 2001: A space Odyssey after finding the classical tracks he used for the temporary soundtrack complement the visuals perfectly. Over the years, some particular pieces of classical music have proven to be very popular and flexible, thus appearing in a wide variety of films across multiple genres. Hence, I have chosen two well known tracks that demonstrate this. I would also like to highlight contemporary classical music and have also selected one example that I feel demonstrates how the genre sublimely compliments cinema.

Classical music has often been used to great effect in cinema since the advent of sound. It has certain advantages over bespoke compositions, in that it can imbue a scene with a sense of gravitas and emotionally connect with viewers who may already be familiar with the piece being played. Legendary director Stanley Kubrick famously rejected Alex North’s score for 2001: A space Odyssey after finding the classical tracks he used for the temporary soundtrack complement the visuals perfectly. Over the years, some particular pieces of classical music have proven to be very popular and flexible, thus appearing in a wide variety of films across multiple genres. Hence, I have chosen two well known tracks that demonstrate this. I would also like to highlight contemporary classical music and have also selected one example that I feel demonstrates how the genre sublimely compliments cinema.

Symphony No7. II. Allegreto (A Minor) by Beethoven.

This rather portentous piece builds over its 9 minute duration. The movement is structured in a double variation form. It starts with the main melody played by the violas and cellos, an ostinato. This melody is then played by the second violins while the violas and cellos play a second melody. Because of the music’s ominous quality it has featured in numerous films. It plays over the montage showing Charlotte Rampling’s and Sean Connery’s ageing and death at the end of John Boorman’s Zardoz (1974). It is also used in Alex Proyas’ science fiction thriller Knowing (2009) when Nicholas Cage returns home to his estranged Father as the world is consumed by solar flares.

Adagio in G minor ("Albinoni's Adagio").

This sombre track is commonly attributed to the 18th-century Venetian master Tomaso Albinoni but was actually composed by 20th-century musicologist and Albinoni biographer Remo Giazotto, purportedly based on the discovery of a manuscript fragment by Albinoni. The piece evokes a sense of loss and melancholia. Hence it was used to great effect in Peter Weir’s influential World War I movie Gallipoli (1981). It features in Kenneth Lonergans’ human drama Manchester by the Sea (2016), although some critics felt that the piece’s ubiquity was actually distracting. Irrespective of this criticism it remains a very moving piece of music.

Lacrimosa by Zbigniew Preisner.

Taken from Polish composer Zbigniew Preisner Requiem for a Friend, this track appears in Terrence Malick’s experimental philosophical drama The Tree of Life (2011). It features during the “creation of the universe” sequence, which is itself a fascinating work of art. This scene, which features practical visual effects by famed special effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull, is further imbued with religious ambience and a sense of the divine by the power of this piece and the beauty of the soprano vocals by Sumi Jo. As the cosmos coalesces, there is a profound sense of both human insignificance and wonder.

Classic Movie Themes: The Pink Panther

If you mention The Pink Panther (1963) I’d hazard a guess that most people will instantly think of Inspector Clouseau (and possibly throw in a quote in faux French about “Minkeys”) or hum or whistle the iconic theme tune. It’s blend of cool sixties Jazz and Lounge is both classy and evocative. Henry Mancini’s contribution to the Pink Panther franchise is commensurate to that of Peter Sellers and Blake Edwards. If you removed his musical scores from any of the films they would be greatly diminished. In fact one can argue that the movies made in the eighties after Sellers’ death are greatly bolstered by Mancini’s intelligent and accomplished musical accompaniment. The franchise may have run out of steam but Mancini never did so.

If you mention The Pink Panther (1963) I’d hazard a guess that most people will instantly think of Inspector Clouseau (and possibly throw in a quote in faux French about “Minkeys”) or hum or whistle the iconic theme tune. It’s blend of cool sixties Jazz and Lounge is both classy and evocative. Henry Mancini’s contribution to the Pink Panther franchise is commensurate to that of Peter Sellers and Blake Edwards. If you removed his musical scores from any of the films they would be greatly diminished. In fact one can argue that the movies made in the eighties after Sellers’ death are greatly bolstered by Mancini’s intelligent and accomplished musical accompaniment. The franchise may have run out of steam but Mancini never did so.

The Pink Panther theme, composed in the key of E minor, is unusual in Mancini's body of work due to its extensive use of chromaticism. In his autobiography Did They Mention the Music? Mancini talked about how he composed the theme music. “I told [the animators] that I would give them a tempo they could animate to, so that any time there were striking motions, someone getting hit, I could score to it.They finished the sequence and I looked at it. All the accents in the music were timed to actions on the screen. I had a specific saxophone player in mind; Plas Johnson. I nearly always precast my players and write for them and around them and Plas had the sound and the style I wanted”.

A Shot in the Dark (1964), like most other movies in the series, featured animated opening titles produced by DePatie-Freleng Enterprises. However, it did not use the iconic Pink Panther theme as an accompaniment on this occasion. Instead Henry Mancini wrote a new musical cue to reflect the fact that Inspector Clouseau was now the main focus of the film. It is a smooth big band piece with a period beatnik vibe. The film blends wordplay with physical comedy and in many ways is the most sophisticated and accomplished of the series. Mancini’s faux ambient Parisian music adds greatly to the atmosphere.

By the time The Pink Panther Strikes Again arrived in cinemas in 1976, director Blake Edwards had moved the focus of the films from straight forward slapstick and Clouseau’s verbal idiosyncrasies to elaborate comedy set pieces featuring destruction and mayhem. The Inspector’s fight with Cato satirises the martial arts trend in movies of the time and the editing style of Sam Peckinpah. The film also features a beautifully simple and low key theme specifically for Clouseau. It plays over a three minute sequence in which the Inspector tries to cross a moat and enter a castle. It underpins Seller’s pratfalls superbly, highlighting the difficulty of scoring comedy successfully. Something Mancini achieve’s here, effortlessly.

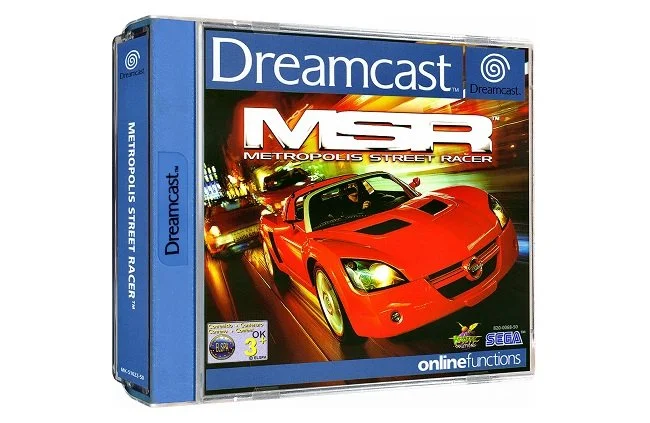

Classic Game Themes: More of my Personal Favourites

Back in August 2018, I posted seven of my favourite tracks from various video games that I’ve played over the years. I thought recently that it was high time that I did the same again. So here are a further five musical cues that I especially enjoy. All of which contribute greatly to the respective games that they feature in. Unlike film composers, musicians that write for video games do not always enjoy comparable exposure or attention. Yet often they have a more complex remit, having to write material for dozens of hours of content, rather than just two or three. Furthermore, the complete soundtrack to many video games often remain conspicuously absent, with fans having to data mine the game client to find the tracks that they love. Which is why it is important for those that enjoy video game music to show their support. Perhaps then more publishers will release full and comprehensive game soundtracks for digital download.

Back in August 2018, I posted seven of my favourite tracks from various video games that I’ve played over the years. I thought recently that it was high time that I did the same again. So here are a further five musical cues that I especially enjoy. All of which contribute greatly to the respective games that they feature in. Unlike film composers, musicians that write for video games do not always enjoy comparable exposure or attention. Yet often they have a more complex remit, having to write material for dozens of hours of content, rather than just two or three. Furthermore, the complete soundtrack to many video games often remain conspicuously absent, with fans having to data mine the game client to find the tracks that they love. Which is why it is important for those that enjoy video game music to show their support. Perhaps then more publishers will release full and comprehensive game soundtracks for digital download.

The Witcher 3 Wild Hunt Blood & Wine: The Slopes Of The Blessure. By Piotr Musial

I enjoyed the Blood & Wine expansion the most out of all the content for The Witcher 3. The region of Toussaint is beautifully realised and oozes charm and sophistication. Based heavily upon the South of France, Piotr Musial’s ambient music reflects this and features a superbly non-ironic use of an accordian.

Guild Wars 2: Heart of Thorns Theme. By Maclaine Diemer

It didn’t take me long to fall out of love with Guild Wars 2 after the arrival of its first expansion. Yet despite the flaws inherent in the new zone, the main theme was not one of them. This pounding motif is both portentous and grandiose. Just listening to it makes me want to return to this MMORPG.

Two Worlds II: The Road is Still Long. By Borislav Slavov

The quality of the soundtrack for Two Worlds II is quite surprising. This is not an RPG produced by a Triple A developer. Yet despite the budget, there is a great deal of depth and musical sophistication to the game’s score. This track which features at the end of the game really nails it with it’s triumphal tone.

Star Trek Online: Age of Discovery Theme. By Kevin Manthei

Kevin Manthei has been the driving force behind the music of Star Trek Online for over a decade. He is dependable, adaptable and totally gets what “Trek” is about. I actually prefer his title music for Age of Discovery more than the official theme for the show itself.

Guild Wars 2: Sanctum Sprint. By Leif Chappelle

The Sanctum Sprint is a high speed race, complete with twitch gaming tactics. It’s frenetic and entertaining (or at least it was when I last played it in late 2015). I’m not quite sure how composer Leif Chapelle concluded that a Mariachi style motif was relevant but it works well and oozes character.

Classic Movie Themes: Friday the 13th

It was Friday the 13th yesterday, so I thought it was about time that I added Harry Manfredini’s iconic score to the annals of Classic Movie Themes. The 1980 slasher movie Friday the 13th has become as legendary in the pantheon of cinematic horror history as John Carpenter’s Halloween. Although there are marked differences between these two films, both use minimalist musical scores extremely effectively to punctuate the proceedings and embellish the overall atmosphere. However, Manfedini did not want to provide viewers with obvious audio cues during scenes of building tension. He preferred to focus his score upon the activities of the franchise's iconic killer, Jason Voorhees, and hence have strong musical cues when he was on screen. This approach meant that he had to use a unique musical motif to denote potential tension, without diminishing its effect on the audience by excessive use of obvious and melodramatic cues.

It was Friday the 13th yesterday, so I thought it was about time that I added Harry Manfredini’s iconic score to the annals of Classic Movie Themes. The 1980 slasher movie Friday the 13th has become as legendary in the pantheon of cinematic horror history as John Carpenter’s Halloween. Although there are marked differences between these two films, both use minimalist musical scores extremely effectively to punctuate the proceedings and embellish the overall atmosphere. However, Manfedini did not want to provide viewers with obvious audio cues during scenes of building tension. He preferred to focus his score upon the activities of the franchise's iconic killer, Jason Voorhees, and hence have strong musical cues when he was on screen. This approach meant that he had to use a unique musical motif to denote potential tension, without diminishing its effect on the audience by excessive use of obvious and melodramatic cues.

Harry Manfredini’s solution was to craft a combination of simple echoing chords combined with a vocal track which repeated the phrase "ki ki ki, ma ma ma". The concept was that these words were some kind of subliminal message; a corrupt version of "kill her, mommy" which would plague Pamela Voorhees, the protagonist from the first movie. Over the course of the franchise, Manfedini became far more adept of using this motif, which he subsequently expanded with the addition of some frenetic strings. This motif would play when something was about to happen on screen, ramping up the tension rather than mitigating it by more overt musical telegraphing. John Williams used a similar technique with his original score for Jaws. Furthermore, Manfredini would often use variations of this cue as musical red herrings, often culminating in a non-fatal jump scare.

Due to the longevity of the Friday the 13th franchise, Harry Manfredini has revised and expanded his work many times. The theme used for the opening credits of the original movie is in many ways the best example. It encapsulates the immediacy of his work and incorporates the "ki ki ki, ma ma ma" motif at its most unique point in history. Another standout version of the main title theme is for Friday the 13th Part III (1982) which was released in 3D. He again reworked the essential principles of basic cue into a pulsing new version with a distinct synth and disco vibe. Finally as an added bonus, I wanted to quickly reference Friday the 13th: A New Beginning (1985) and the song that features while Violet (Tiffany Helm) indulged in that very eighties activity, robot dancing. His Eyes by Australian New Wave Band (and shameless Ultravox plagiarists) Pseudo Echo has gained a curious cult following over the years among Friday the 13th fans.

Classic Movie Themes: Game of Death

Game of Death was Bruce Lee’s fourth Hong Kong martial arts movie. Due to the success of his previous films he found himself in a position where he could finally write and direct a project himself. Filmed in late 1972 and early 1973, the film was put on hold midway through production when Hollywood offered him a starring role in Enter the Dragon. He died shortly after completing the US backed movie that made him an international star, so Game of Death remained unfinished. Several years later the rights to the raw footage were sold and recycled for a new movie, that kept the name but bore little resemblance to Lee’s original vision. For most of Game of Death, Kim Tai-jong and Yuen Biao double for Bruce Lee and it is only in the final act that audiences actually get to see about 12 minutes of material that he shot himself. The 1978 release of Game of Death, directed by Robert Clouse, is a mess but remains a cinematic curiosity. The scenes which genuinely feature Bruce Lee are outstanding, even in an abridged form.

Game of Death was Bruce Lee’s fourth Hong Kong martial arts movie. Due to the success of his previous films he found himself in a position where he could finally write and direct a project himself. Filmed in late 1972 and early 1973, the film was put on hold midway through production when Hollywood offered him a starring role in Enter the Dragon. He died shortly after completing the US backed movie that made him an international star, so Game of Death remained unfinished. Several years later the rights to the raw footage were sold and recycled for a new movie, that kept the name but bore little resemblance to Lee’s original vision. For most of Game of Death, Kim Tai-jong and Yuen Biao double for Bruce Lee and it is only in the final act that audiences actually get to see about 12 minutes of material that he shot himself. The 1978 release of Game of Death, directed by Robert Clouse, is a mess but remains a cinematic curiosity. The scenes which genuinely feature Bruce Lee are outstanding, even in an abridged form.

Game of Death was marketed to capitalise on Lee’s international fame and appeal. Due to his iconic status it was packaged in a comparable idiom to a Bond film. Hence the opening credits to Game of Death are lurid and literal; very much like the work of Maurice Binder on the various James Bond movies. And then there is the score by John Barry that lends a certain classy ambience to the proceedings. The main theme is brassy, sumptuous and oozes style in the same way that Barry brought those qualities to the 007 franchise. Variations of this cue are subsequently used during all the major fight scenes in the film. Musically it works best with the footage in the film’s climax which was shot by and features Lee himself. The presence of such a noted film composer elevates the status of Game of Death, despite its many flaws. However, the Catonese and Mandarin dialogue versions of the movie feature an alternative soundtrack by Joseph Koo, who was an established composer in the Hong Kong movie industry.

The complete soundtrack for Game of Death was recently released by Silva Screen and also includes the score for Roger Vadim’s Night Games from 1980. The soundtrack contains all major cues featured in the film along with the song “Will This Be The Song I'll Be Singing Tomorrow” performed by Colleen Camp, who also starred in the film. I suspect it was hoped that this number would do well on the strength of the movie but it is far from memorable with its overly fastidious lyrics and melancholy tone. Here is the main title theme which underpins Game of Death. It is instantly recognisable as a John Barry compositions, as it exhibits all his musical hallmarks. It is far more grandiose in its scope than the quirky scores of Bruce Lee’s earlier work. If Lee had lived perhaps the Hollywood studios would have attempted to pigeonhole him into more sub Bond style movies as Game of Death strives to. Irrespective of such idle speculation, John Barry’s work remains as iconic as Lee himself and effortless reflects his charisma and physical prowess.

Classic Movie Themes: The Long Good Friday

The Long Good Friday not only launched then career of Bob Hoskins but remains a uniquely British take on the gangster genre. Featuring authentic performances and a credible plot, the screenplay touches upon many of the social and political issues of the time; police corruption, the IRA, urban renewal and the decline of industry, along with EEC membership and the free-market economy. It’s a gritty and unrelenting drama that is still relevant today. Furthermore, the film is filled with quotable dialogue and has several stand out scenes that showcase Bob Hoskins’ smouldering performance. It’s also offers of “who’s who” of British character actors and there is one sequence still has the power to shock even today.

The Long Good Friday not only launched then career of Bob Hoskins but remains a uniquely British take on the gangster genre. Featuring authentic performances and a credible plot, the screenplay touches upon many of the social and political issues of the time; police corruption, the IRA, urban renewal and the decline of industry, along with EEC membership and the free-market economy. It’s a gritty and unrelenting drama that is still relevant today. Furthermore, the film is filled with quotable dialogue and has several stand out scenes that showcase Bob Hoskins’ smouldering performance. It’s also offers of “who’s who” of British character actors and there is one sequence still has the power to shock even today.

One of the many elements that contribute to The Long Good Friday being such a seminal movie is the score by Francis Monkman. A classically trained composer, conversant with multiple musical instruments, Monkman’ was the founder member of both the bands Curved Air and Sky. His score is a striking electronic synth hybrid featuring the talents of Herbie Flowers, Kevin Peek, and Tristan Fry. The addition of Stan Sulzmann and Ronnie Aspery on saxophone lends an interesting juxtaposition to the various tracks. It’s all evocative of mid-seventies UK police procedurals dramas with a blend of pulsing synths that you found in TV science fiction at the time. Yet despite its curious antecedents, it works very well on screen reflecting the story’s themes of old giving way to the new.

The Long Good Friday title theme is a brassy, pulsing affair. It is used several times throughout the film and works the best in an early scene when Harold Shand (Bob Hoskins) arrives at Heathrow airport after a flight on Concorde. It superbly establishes his character as he confidently strolls through customs after setting up a major deal with the Mafia in the US. “Fury” is a very interesting cue as it starts with a dark electronic passage as the Harold discovers the magnitude of his predicament. It evolves into a powerful and soulful sax driven piece as Harold washes the blood from himself after a frenzied attack. Both tracks are from the recent anniversary soundtrack album where the remastered score is finally available in stereo.

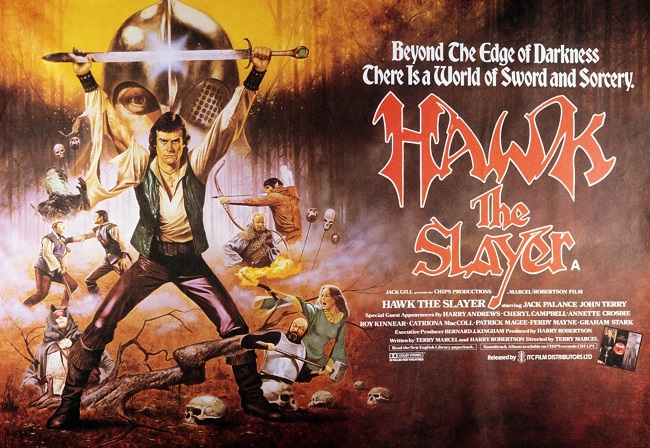

More Cult Movie Soundtracks

A few years ago, I wrote a post about cult movie soundtracks and how many of these movies are often blessed with a high quality score from an established composer. The subject came up again recently when I was visiting the British Film Institute with friends, and several other examples were discussed. Hence, I thought it would be prudent to write a follow up post with another selection of material, as it continues to amaze me how often the most appalling films can still have outstanding soundtracks. With this idea in mind I've collated five films that are for various reasons are labelled “cult” and have suffered the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” over the years. All have scores of interests and note, though for different reasons. I have chosen a track from each soundtrack which I think highlights the musical excellence and integrity of the composers involved. The genres are varied as are the musical styles and nuances of each piece. All clearly demonstrate how a well-conceived score can embellish and enhance a movie, effectively becoming a character in its own right.

A few years ago, I wrote a post about cult movie soundtracks and how many of these movies are often blessed with a high quality score from an established composer. The subject came up again recently when I was visiting the British Film Institute with friends, and several other examples were discussed. Hence, I thought it would be prudent to write a follow up post with another selection of material, as it continues to amaze me how often the most appalling films can still have outstanding soundtracks. With this idea in mind I've collated five films that are for various reasons are labelled “cult” and have suffered the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” over the years. All have scores of interests and note, though for different reasons. I have chosen a track from each soundtrack which I think highlights the musical excellence and integrity of the composers involved. The genres are varied as are the musical styles and nuances of each piece. All clearly demonstrate how a well-conceived score can embellish and enhance a movie, effectively becoming a character in its own right.

I've always found it paradoxical that a movie such as Ruggero Deodato's notorious Cannibal Holocaust (1980), features such a haunting score by Riz Ortolani. I won't debate the merits of Cannibal Holocaust here but it’s a very morally ambiguous and controversial piece of cinema. It’s certainly not for those who are easily shocked. Yet its soundtrack underpins the narrative superbly. The opening theme, set against aerial shots of the Amazon rain forest, features a very gentle and haunting refrain. You would think such a piece would be more at home in a romantic drama or even a late seventies commercial. However, it is further repeated at various times during the film, often juxtaposed against scenes of abject barbarity.

Solomon Kane (2009), based on Robert E. Howard’s fictional "dour English Puritan and redresser of wrongs", is an underrated action horror movie. It manages to bely its modest production values to blend atmospheric European locations with a strong cast. The action is robust and James Purefoy carries the story forward and compensates for some of the film’s logistical failings. The tone and spirit of the proceedings is very much in the idiom of Hammer movies such as Captain Kronos. The score by German composer Klaus Badelt is grandiose and focuses on the central character of Kane. The main theme is used with suitable variations to reflect both the bombastic fights sequences and the moments of quiet religious reflection.

How can I possibly write about cult, obscure and trash movie soundtracks without at least one piece by the legendary Ennio Morricone. The maestro seems to have a knack of writing quality material for some awful films. Hundra (1984) is an Italian-Spanish fantasy film co-written and directed by Matt Cimber and starring Laurene Landon. It’s a kind of female Conaneque, sword and sorcery movie with a bogus feminist agenda. Beneath a wafer-thin veneer of gender politics is a generic exploitation movie. The actions scenes are weak, the story is formulaic and the performances are negligible due to the ADR inherent in such international co-productions. Yet the Morricone score stands out. Hundra’s main theme is simple and effective and there’s a chase scene with a whimsical accompaniment.

Lucio Fulci’s first instalment of his “Gates of Hell” trilogy is an atmospheric, off kilter horror outing. City of the Living Dead (1980) features his hallmark excessive gore but unlike his previous movie Zombie 2, the linear narrative is replace with a more dream like story line. Many scenes are visually striking but the plot doesn’t really make logical sense. However there are sufficient maggots raining from the ceiling and actors vomiting up their intestines to keep the audience focused elsewhere. The soundtrack by Italian composer Fabio Frizzi is creepy and uniquely European. The scene in the crypt at the climax of the movie has a great cue that plays as zombies stagger around burning.

If you are not familiar with Michael Mann’s The Keep (1983), then it’s difficult to know where to start. The film is based upon a gothic horror novel by F. Paul Wilson about a group on German soldiers based in a Romanian fortress during World War II, who are picked off one by one by a vampire like creature. Mann’s second feature film took this tale and adapted it into a curious science fiction horror movie. The production was “difficult”, ran over budget and studio executives panicked at the kind of experimental film making that ensued. The movie was taken away from the director, re-edited and released in a very truncated form. It failed at the box office and Mann has subsequently disowned it. It boasts a sophisticated soundtrack by German electronic music band Tangerine Dream. Like the film itself, the score just has to be experienced and digested to be fully appreciated. Similarly, the score has had a troubled life and there has never been an official release that contains all music used. But what remains is intriguing even when listened to outside of the context of the film itself.

Classic Game Themes: Lords of the Fallen

Lords of the Fallen is an action role-playing game from 2014, played from a third-person perspective. It is broadly in the same idiom to Darksiders and Dark Souls with the emphasis on complex and challenging combat. And it is for that reason that I didn’t get on with this title when I bought it in a Steam sale a few years ago. I felt that the long, protracted fights were an impediment to the narrative, which I quite enjoyed. However, the game was designed this way to appeal to the combat focused gamer and “git gud” culture. But I think that it’s important to try different genres of games from time to time and to step occasionally out of your comfort zone. I would cite the Hand of Fate series as a positive example of this. Both of those titles are from a genre I wouldn’t usually consider and playing them turned out to be a very positive experience

Lords of the Fallen is an action role-playing game from 2014, played from a third-person perspective. It is broadly in the same idiom to Darksiders and Dark Souls with the emphasis on complex and challenging combat. And it is for that reason that I didn’t get on with this title when I bought it in a Steam sale a few years ago. I felt that the long, protracted fights were an impediment to the narrative, which I quite enjoyed. However, the game was designed this way to appeal to the combat focused gamer and “git gud” culture. But I think that it’s important to try different genres of games from time to time and to step occasionally out of your comfort zone. I would cite the Hand of Fate series as a positive example of this. Both of those titles are from a genre I wouldn’t usually consider and playing them turned out to be a very positive experience.

One aspect of Lords of the Fallen that did stand out for me, was the score by Norwegian composer Knut Avenstroup Haugen. Haugen is best known for his association with video game developers Funcom and writing the soundtrack for Age of Conan. His work on that MMO was very broad in scope, encompassing inspiration from a wide variety of world cultures. However, his approach for Lords of the Fallen is quite different. The main title cue is a simple track which blends ethereal vocalisations and strings with a strong percussive beat. This surprisingly versatile leitmotif is subsequently used in interesting variations throughout the game. This very clear musical style reflects the games central theme of an individual on a path of self-discovery and bolsters it very effectively.

To highlight how well Knut Avenstroup Haugen uses the concept of the leitmotif in Lords of the Fallen, here are three tracks from the game’s soundtrack album. “Winter’s Kiss (Theme from Lords of the Fallen)” which establishes the central musical concept. “Sacrifice” which presents a robust variant as the main character progresses through the game’s narrative. And finally, “Atonement” which beautifully adapts the main theme to a triumphant and emotional end piece. It should be noted that the score Lords of the Fallen was nominated for the Hollywood Music in Media Awards by critics. This was due to its adaptable simplicity which lends itself to significant variation and interpretation.

Classic Movie Themes: Alien

Alien is a unique genre milestone. It challenged the established aesthetic created by 2001: A Space Odyssey of space travel being pristine, clinical and high tech and replaced it with a grimy, industrial quality. The space tug Nostromo is also a conspicuously “blue collar”, civilian venture, underwritten by a large corporation. As for H. R Giger’s xenomorph, it redefined the depiction of extraterrestrial life in movies. Director Ridley Scott brought visual style and atmosphere to particularly unglamorous and dismal setting. He also scared the hell out of audiences at the time with his slow burn story structure and editing style that hints, rather than shows. Overall, Alien is a text book example of how to make a horror movie and put a new spin on a classic and well-trodden concept.

Alien is a unique genre milestone. It challenged the established aesthetic created by 2001: A Space Odyssey of space travel being pristine, clinical and high tech and replaced it with a grimy, industrial quality. The space tug Nostromo is also a conspicuously “blue collar”, civilian venture, underwritten by a large corporation. As for H. R Giger’s xenomorph, it redefined the depiction of extraterrestrial life in movies. Director Ridley Scott brought visual style and atmosphere to particularly unglamorous and dismal setting. He also scared the hell out of audiences at the time with his slow burn story structure and editing style that hints, rather than shows. Overall, Alien is a text book example of how to make a horror movie and put a new spin on a classic and well-trodden concept.

Jerry Goldsmith’s sombre and portentous score is a key ingredient to the film’s brooding and claustrophobic atmosphere. Yet despite the quality of the music, Goldsmith felt that the effectiveness of his work was squandered by Ridley Scott and editor Terry Rawlings who re-edited his work and replaced entire tracks with alternative material. However what was left still did much to create a sense of romanticism and mystery in the opening scenes, then later evolving into eerie, dissonant passages when the alien starts killing the crew. The fully restored score has subsequently been released by specialist label Intrada and has a thorough breakdown of its complete and troubled history.

Perhaps the best track in the entire recording is the triumphant ending and credit sequence, which was sadly removed from the theatrical print of the film and replaced with Howard Hanson's Symphony No. 2 ("Romantic"). This cue reworks the motif from the earlier scene when the Nostromo undocks from the refining facility and lands on the barren planet, LV-426. It builds to a powerful ending which re-enforces Ripley’s surprise defeat of the xenomorph and its death in the shuttles fiery exhaust. Seldom has the horror genre been treated with such respect and given such a sophisticated and intelligent score. Despite its poor handling by the film’s producers, Alien remains one of Jerry Goldsmith’s finest soundtracks from the seventies and yet another example of his immense talent.

Classic Movie Themes: Star Trek II The Wrath of Khan

James Horner was a prolific, yet consistently good composer with a broad range of styles. Consider his score for 48 Hrs with its Jazz under currents and then compare it to his grand swashbuckling approach to Krull. They are radically different soundtracks, but both are extremely effective in embellishing their respective motion pictures. That was James Horner great talent. He knew when to be theatrical and bombastic but could also dial it back and be subtle, gentle and delicate. It made his body of work very diverse and memorable.

James Horner, although possessing a very broad and eclectic musical range, was in many respects a very traditional composer. He was certainly au fait with works of such giants as Miklós Rózsa, Korngold and Bernard Herrmann and it often manifested itself in his music through his use of the leitmotif. Perhaps the reason James Horner was so consistently good and crafted so many outstanding pieces of music, is because he never saw his profession as just a means to an end. As he said in an interview once, “I don’t look at this as just a job. I see music as art”.

James Horner was a prolific, yet consistently good composer with a broad range of styles. Consider his score for 48 Hrs with its Jazz under currents and then compare it to his grand swashbuckling approach to Krull. They are radically different soundtracks, but both are extremely effective in embellishing their respective motion pictures. That was James Horner great talent. He knew when to be theatrical and bombastic but could also dial it back and be subtle, gentle and delicate. It made his body of work very diverse and memorable.

James Horner, although possessing a very broad and eclectic musical range, was in many respects a very traditional composer. He was certainly au fait with works of such giants as Miklós Rózsa, Korngold and Bernard Herrmann and it often manifested itself in his music through his use of the leitmotif. Perhaps the reason James Horner was so consistently good and crafted so many outstanding pieces of music, is because he never saw his profession as just a means to an end. As he said in an interview once, “I don’t look at this as just a job. I see music as art”.

James Horner was very much part of my cinematic youth, having written the soundtracks for many of my favourite movies. I first encountered his work when I saw Battle Beyond the Stars and was immediately captivated by its bold and brass driven title theme. It was this particular soundtrack that brought him to the attention of Paramount Studios and led to him composing his seminal score for Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan with its graceful nautical themes. The film's director Nicholas Meyer famously quipped that Horner had been hired because the studio couldn't afford to use the first film's composer Jerry Goldsmith again. By the time Meyer returned to the franchise with Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, the director found that he couldn't afford Horner either.

Classic TV Themes: Star Trek Enterprise

Star Trek: Enterprise was the first show in the Star Trek pantheon to have a song performed by an established artist play over the opening credits, rather than a traditional theme tune. Up until 2001, the franchise had maintained a more formal approach, established with the iconic introduction to the original series composed by Alexander Courage. Needless to say, such a radical departure from established practise brought about consternation and debate among fans. In some respects, you can argue that point about the entire show itself, but that as they say, is an entirely different blog post. Needless to say, the dislike and hatred that the song Where My Heart Will Take Me engendered in certain quarters, lead to a petition to have it removed. Needless to say, this movement failed, and the show continued using it for four seasons. Seventeen years on this particular debacle has now died down and the song is often just referenced ironically by fans as an amusing anecdote and piece of Trek trivia.

Star Trek: Enterprise was the first show in the Star Trek pantheon to have a song performed by an established artist play over the opening credits, rather than a traditional theme tune. Up until 2001, the franchise had maintained a more formal approach, established with the iconic introduction to the original series composed by Alexander Courage. Needless to say, such a radical departure from established practise brought about consternation and debate among fans. In some respects, you can argue that point about the entire show itself, but that as they say, is an entirely different blog post. Needless to say, the dislike and hatred that the song Where My Heart Will Take Me engendered in certain quarters, lead to a petition to have it removed. Needless to say, this movement failed, and the show continued using it for four seasons. Seventeen years on this particular debacle has now died down and the song is often just referenced ironically by fans as an amusing anecdote and piece of Trek trivia.

As for the song itself, it has quite an interesting history. It was originally called Faith of the Heart and was written by songwriter Dianne warren, who has a history of penning songs for the likes of Whitney Houston, Barbara Streisand and Aretha Franklin. Faith of the Heart was originally recorded by Rod Stewart and featured in the Robin Williams movie Patch Adams in 1999. It was subsequently covered by country artist Susan Ashton. Broadly both these versions were well received. English tenor Russell Watson then covered the song on his 2001 album Encore under the title Where My Heart Will Take Me. It is this version that is used on the first two seasons of Star Trek: Enterprise albeit in an edited version, reducing a 4.14-minute recording to a more appropriate 1:28-minutes to accommodate the opening credits. This version is very much a power ballad and very much wears its heart on its sleeve, candidly extoling the sort of sentiment and philosophy of Starfleet. The song is intended to be a metaphor for earth struggle to reach the stars and the challenges ahead. Curiously, from season three onwards, the song was re-recorded again with Russell Watson but with a more upbeat tempo. It is quite a different arrangement.